Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:22 — 19.2MB)

Subscribe: | More

This is a chapter of the Beyond Bigfoot and Nessie book, which you can buy or request at the library!

Further reading:

Debunking a Great New England Sea Serpent

A narwhal. I use this picture all the time:

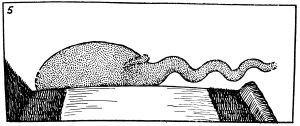

The diseased black snake that was taken for a baby sea serpent:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to have a sea monster episode! This is actually a chapter of the book that I published a few years ago now, Beyond Bigfoot and Nessie, and it’s called the Gloucester Sea Serpent. We had a Patreon episode recently that was about a different sea serpent, and while I was researching that, it was driving me completely nuts, because I kept trying to find the episode where I talked about the Gloucester sea serpent, and I finally remembered that that wasn’t an episode at all. It was just a chapter in the book. Maybe it’s time to record it.

While the Gloucester sea serpent was first mentioned in a traveler’s journal in 1638, it really came to prominence almost two centuries later. On August 6, 1817, two women said they’d seen a sea monster in the Cape Ann harbor. A fisherman said he’d seen it too, but neither the fisherman nor the women were believed. A 60-foot, or 18-meter, sea serpent in the harbor? Ridiculous!

Only a few days later, though, the monster started showing up in Gloucester Bay and attracted major attention—not because it was elusive, but because it was so commonly seen. Sailors, fishers, and even people on shore saw what was described as a huge serpent in the waters of Gloucester Bay, Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. On one occasion more than two hundred people watched it for nearly four hours.

The creature’s length was described as anywhere up to 150 feet long, or 46 meters, and many people said it had a horse-sized head. Some people described its head as being about the same shape as a horse’s too, although with a shorter snout. The body was snake-like and about the thickness of a barrel.

Many people thought the sea monster had humps along the back, usually referred to as bunches or occasionally joints. Others said it undulated through the water in an up-and-down motion, which looked like humps. Others said it had no bunches or humps at all. Most people agreed that its back was dark brown.

One of the earlier witnesses, a man named Amos Story, watched the sea serpent from shore for an hour and a half. He was adamant that it had no bunches, that he only saw at most about 12 feet of its length at one time, or 3.6 meters, and that its head resembled that of a sea turtle. It was also fast, with Story claiming it covered a mile in only three minutes or so. That’s about 20 miles per hour, or 32 kilometers per hour—an incredible speed for an animal in the water.

As it happens, the leatherback sea turtle has been recorded as swimming that fast, and it can grow over 7 feet long, or 2.2 meters, and possibly much longer. It lives throughout the world’s oceans and is just as happy in cold waters as it is in tropical waters. In other words, it’s possible Story actually saw a huge leatherback turtle, which would explain why it had a turtle-like head that it held above the surface of the water at least part of the time. This is something leatherback turtles do. Then again, the leatherback has distinctive ridges and serrations on its back that Story didn’t mention.

So many people reported seeing the sea serpent that the Linnaean Society of New England decided it needed to investigate. The society had only formed a few years before, in 1814, to promote natural history. By 1822 it had disbanded, but in those eight years it accomplished quite a bit, including opening a small museum in Boston. Its most controversial endeavor was the sea serpent investigation.

Members of the Linnaean Society interviewed witnesses, making careful notes that were signed by the interviewees to indicate the details were accurate. These statements tell us a lot about what people saw, although it hasn’t helped us determine what the sea serpent actually was.

For instance, Captain Solomon Allen saw the creature more than once and gave a clear description of it. It was at least 90 feet long, or 27.5 meters, with as many as fifty joints, or bunches. Its head was snake-like—specifically rattlesnake-like, presumably meaning it was wider at the back and had a narrower snout—but the size of a horse’s head. It was dark brown, plain in color, and swam with an undulating side-to-side motion. It dived by sinking straight down, moved quickly, and sometimes seemed to play in the water by swimming in circles.

All this is great information, but it doesn’t resemble any known animal. It also doesn’t necessarily resemble the other witness statements. Let’s go over some of the more detailed sightings and see if we can come to some conclusions.

A man named William Foster reported bunches along the monster’s length, although he also described them as rings. When the animal’s head rose from the water, the first thing Foster saw was what he described as a prong or spear. It was about a foot long, or 30 centimeters, and tapered to a point. His interviewer asked if the spear might have been a tongue, but Foster didn’t think so.

Three men on a schooner named the Laura, becalmed in the mouth of the harbor, witnessed the monster in late August. Sewall Toppan, master of the ship, reported that the monster’s head was the size of a 10-gallon keg, which would have been about 18 inches tall, or 46 centimeters, and 16 inches in diameter, or 40 centimeters. He said its head was held about 6 inches out of the water, or 15 centimeters, and that he could see 10 or 15 feet of its length disappearing into the water, or 3 to 4.5 meters. He didn’t see any kind of prong, but two of his sailors did.

One of the two sailors was Robert Bragg, who reported that the monster was swimming rapidly toward the ship with its head and about 15 feet of its body out of the water, or 4.5 meters. As it drew closer he saw its tongue, which he described as looking like a harpoon about 2 feet long, or 61 centimeters. He even reported that the animal raised its tongue almost straight up several times. He also said it was dark brown and smooth.

The third Laura witness, helmsman William Somerby, corroborated Bragg’s details, including the animal’s tongue, which he mentioned was light brown. As the monster passed within 40 feet of the ship, or 12 meters, Somerby even saw one of its eyes clearly. He said it was the size of an ox’s eye and was completely dark brown or possibly black. He and Bragg both noted that the animal had a bunch above its eyes, presumably meaning a bump or knob of some kind.

All three men said that they were familiar with whales and the animal was not a whale.

August 14 was a warm day and the water was calm. A man named Matthew Gaffney, a ship’s carpenter by trade but in his heart a monster hunter, borrowed a boat and took his brother and a friend with him to row. He also took a musket.

As the small boat approached cautiously, the monster was spiraling around in the water, as various people reported it doing on and off throughout the day. Gaffney waited until the boat was as close as it could safely approach without risking being capsized, then fired a shot at the monster’s head.

He was a good marksman and was certain he hit the animal, which sank immediately below the surface and vanished. Worried that the wounded monster would be enraged once its initial shock wore off, Gaffney and all the other boats on the harbor took off for shore. But when the sea monster resurfaced some distance off, it was obviously unbothered by being shot at. It continued its apparently playful circling around in the harbor.

Several witnesses who saw the monster on August 14, before and after Gaffney’s attempt to shoot it, gave statements. William H. Foster said it at first moved slowly, but then sped up and twisted and turned through the water. Sometimes its head would bend around toward its tail, and Foster specifically said that when that happened, parts of its body between the bunches would raise up as much as 8 inches out of the water, or 20 centimeters, showing that the animal was at least 40 feet long, or 12 meters.

Lonson Nash saw the sea serpent and reported that it moved quickly and left a long wake, and that while it swam underwater sometimes, it didn’t seem to be very far under. He could track its progress underwater by the disturbance it made on the surface. He also saw it double around so that its head was sometimes near its tail, but he mentioned that when it was swimming forward, it appeared perfectly straight.

Later that day, a shipmaster named Epes Ellery saw the monster’s head through a spyglass. He reported that it was flattened on top like a snake’s and that its mouth resembled a snake’s mouth—presumably meaning it had a thin lower jaw. He reported that its joints were the size of two-gallon kegs and rose about 6 inches above the surface, or 15 centimeters. He said the animal swam with a vertical motion, not a side-to-side motion.

An unnamed woman reported that the sea monster’s bunches looked like gallon kegs tied in a line. Another man said he saw the creature’s bunches at the surface as it lay still for a while, and that around 50 feet, or 15 meters, of its length was visible although he couldn’t see its head or tail. Other witnesses that same day reported much the same thing.

Captain Elkanah Finney saw the sea monster from shore later in August, after his son reported seeing something strange in the harbor. Finney first thought it was a bunch of seaweed, but when he looked at it through his spyglass he realized it was an animal moving quickly through the water. He said it might have been 100 feet long, or 30 meters, with 30 or 40 bunches down its length. In fact, he said it looked like a string of buoys and that each bunch was about the size of a barrel.

There are lots of other reports, all of them similar to these. The sea monster, whatever it was, spent a lot of time in and around Gloucester Bay that summer and even returned the following two summers. People were obviously seeing something. The question is what.

Let’s look at the sightings where the monster had a prong or that it stuck out a long, straight tongue. This sounds a lot like a narwhal. A narwhal can grow up to about 18 feet long, or 5.5 meters, and males, and some females, have a brown or brownish spiral tusk that can grow just over 10 feet long, or 3 meters. Many people think the narwhal’s tusk is a horn that sticks up from its forehead, but it’s actually an elongated tooth that grows through the upper lip. That would explain why some of the witnesses thought it was a tongue.

A young narwhal is black or dark brown, although it grows lighter throughout its life so that old narwhals are almost white. A young animal would also have a short tusk. A narwhal often swims with its head out of the water and a male will sometimes lift his tusk up and down in the air. He can do this easily because, unlike most whales, the narwhal’s neck vertebrae aren’t fused and can bend the head around.

Most importantly, the narwhal is an Arctic animal and isn’t typically found as far south as Massachusetts, although it’s certainly been seen in that part of the ocean on rare occasions. Its rareness, together with its odd appearance compared to other whales, might lead witnesses to think it wasn’t a whale at all but some kind of monster.

That doesn’t explain the bunches, though. The witnesses on the schooner Laura didn’t report seeing any bunches on their sea monster (whose “tongue” reportedly looked like a harpoon), but William Foster’s pronged sea monster did have bunches.

Some researchers have dismissed the bunches, or humps, as a string of narwhals or other small whales traveling in a line. That’s definitely a possibility, but too many witnesses described the bunches as being always partially out of the water, not moving up and down. Not only that, the bunches were seen when the sea monster was lying quietly on the placid surface, not moving, often for long stretches.

Remember, though, that many witnesses described the bunches as resembling a line of buoys or kegs tied on a line. The animal often seemed to swim in circles until its head nearly touched its tail. William Foster reported that when it did this, its body between the bunches would rise several inches out of the water. Lonson Nash said when it was swimming forward, its body appeared perfectly straight.

Maybe witnesses weren’t seeing a long serpentine animal with bumps along its back. Maybe they were seeing a string of kegs used as buoys to keep fishing nets afloat, that had become tangled around a small whale’s tail.

Small kegs or large pieces of cork were sometimes used for this purpose at the time, including in Newfoundland and Norway. If a net tangled around a narwhal’s tail, the animal might have become used to dragging its burden around until the net eventually rotted away and freed the whale. This is something that still happens to whales today with nets and other fishing gear, although these days the nets are all plastic and won’t rot.

Narwhals mostly eat fish and squid, and often dive deeply to find food along the ocean floor. Our entangled narwhal chasing fish underwater might appear to be traveling in playful circles as the net dragged along behind and above it. Pulling all the buoys underwater would probably be difficult for the whale, which would explain why it mostly stayed near the surface.

It’s not a perfect match, of course, but the tangled-narwhal hypothesis fits a lot of the details reported for the Gloucester sea serpent. Narwhals also often travel in small groups, so if the entangled narwhal was with a few friends, that would explain why not every witness saw the bunches.

As for the Linnaean Society of New England, their investigation of the sea monster was excellent for the time. They took the sightings seriously and tried to remain impartial, although the members did seem to start from an assumption that the animal was an actual serpent of some kind.

Unfortunately, they made one fatal blunder. In late September 1817, someone found and killed a snake 3.5 feet long, or a little over a meter, that had bunches all down its spine. It was found only a few miles from Gloucester Harbor. The Linnaean Society decided it had to be a baby sea serpent.

They said so loudly and even proposed a scientific name for the sea serpent. But it wasn’t long before the “baby sea serpent” was identified as a common black snake. The body was dissected and the bunches turned out to be tumors from a diseased spine. The society’s investigation became a joke. But at least we still have the eyewitness accounts they gathered.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!