Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:36 — 12.6MB)

Further reading:

Audubon’s Bird of Washington: Unraveling the fraud that launched The Birds of America

The Mystery of the Missing John James Audubon Self-Portrait

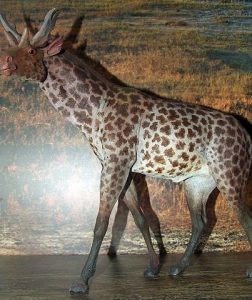

Washington’s eagle, as painted by Audubon:

The tiny detail in Audubon’s golden eagle painting that is supposed to be a self-portrait:

The golden eagle painting as it was published. Note that there’s no tiny figure in the lower left-hand corner:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This past weekend I was out of town, or to be completely honest I will have been out of town, because I’m getting this episode ready well in advance. Since July 4 was only a few days ago, or will have been only a few days ago, and July 4 is Independence Day in the United States of America, I thought it might be fun to talk about a very American bird, Washington’s eagle.

We talked about it before way back in episode 17, and I updated that information for the Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie book for its own chapter. When I was researching birds for episode 381 I revisited the topic briefly and realized it’s so interesting that I should just turn it into a full episode.

We only have two known species of eagle in North America, the bald eagle and the North American golden eagle. Both have wingspans that can reach more than 8 feet, or 2.4 meters, and both are relatively common throughout most of North America. But we might have a third eagle, or had one only a few hundred years ago. We might even have a depiction of one by the most famous bird artist in the world, James Audubon.

In February 1814, Audubon was traveling on a boat on the upper Mississippi River when he spotted a big eagle he didn’t recognize. A Canadian fur dealer who was with him said it was a rare eagle that he’d only ever seen around the Great Lakes before, called the great eagle. Audubon was familiar with bald eagles and golden eagles, but he was convinced the “great eagle” was something else.

Audubon made four more sightings over the next few years, including at close range in Kentucky where he was able to watch a pair with a nest and two babies. Two years after that he spotted an adult eagle at a farm near Henderson, Kentucky. Some pigs had just been slaughtered and the eagle was looking for scraps. Audubon shot the bird and took it to a friend who lived nearby, an experienced hunter, and both men examined the body carefully.

According to the notes Audubon made at the time, the bird was a male with a wingspan of 10.2 feet, or just over 3 meters. Since female eagles are generally larger than males, that means this 10-foot wingspan was likely on the smaller side of average for the species. It was dark brown on its upper body, a lighter cinnamon brown underneath, and had a dark bill and yellow legs.

Audubon named the bird Washington’s eagle and used the specimen as a model for a life-sized painting. Audubon was meticulous about details and size, using a double-grid method to make sure his bird paintings were exact. This was long before photography.

So we have a detailed painting and first-hand notes from James Audubon himself about an eagle that…doesn’t appear to exist.

Audubon painted a few birds that went extinct afterwards, including the ivory-billed woodpecker and the passenger pigeon, along with less well-known birds like Bachman’s warbler and the Carolina parakeet. He also made some mistakes. Many people think Washington’s eagle is another mistake and was just an immature bald eagle, which it resembles.

But here’s the problem. Audubon wasn’t always truthful. He painted some birds that he never saw but claimed he did, because another bird illustrator had painted them first. Once he claimed he went hunting with Daniel Boone in Kentucky in 1810, but at that time Boone would have been in his 70s and was living several states away.

Audubon also claimed that he discovered a little bird called Lincoln’s sparrow, but this wasn’t the case. His wife’s transcript of his diary doesn’t match up with the account that Audubon published about the discovery, but magically, when his granddaughter published her version of the diary later, Audubon’s discovery of the sparrow was in it. Historians think his granddaughter changed the diary entry to match up with Audubon’s published claim, and then she burned the original diaries. Further research into Audubon’s published writings have revealed plagiarism, false data, outright lies, and even completely fake species.

Audubon was also patriotic, as evidenced by his naming the eagle after George Washington. His journals and letters are full of praise for Washington, who died in 1799, only fifteen years before Audubon first saw the “great eagle.” There’s always a chance that Audubon wanted to name a bird after his idol, but not just any bird. It had to be majestic and bold, the largest eagle in the world! Maybe he decided to invent one.

Audubon also needed money to continue his work of painting birds, and most of the money came from English nobility. His painting and notes about a gigantic eagle made a real splash, bringing him money and fame for the rest of his life. But no evidence of the eagle’s existence has been discovered in the last 200 years. All we have are one man’s notes, a painting, and some stories of other specimens here and there. What we don’t have are the specimens, not even any feathers.

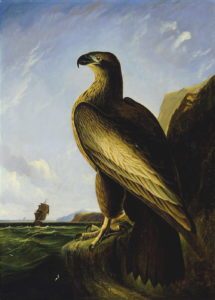

While we’re talking about one Audubon eagle mystery, let’s learn about another mystery. While Audubon was an incredible painter of birds, he wasn’t all that great at painting people. Only two of his famous bird paintings contain human figures, and one of them is his painting of the golden eagle. The other is a hunter painted in the background of the snowy egret, but Audubon didn’t paint that figure himself. He painted the bird, but hired another artist to paint the background. But this isn’t the case for the golden eagle painting, and that’s where the mystery lies. Even though it’s not technically anything to do with the bird, I know we’re all here for a good mystery too, so let’s talk about this painting.

Most of the time Audubon shot the birds he painted, which isn’t a great thing to do but which was common back then for scientists and collectors to shoot even very rare animals. Few people really understood conservation at the time. In the case of the golden eagle, though, the bird was already so rare in the early 19th century that Audubon couldn’t find one to shoot. He eventually bought one from a museum in 1833—but the bird wasn’t dead. It was injured, and Audubon was so impressed by its beauty that he almost set it free. But he needed to paint the bird, and in order to do that to his own meticulous standard, the bird had to be dead so he could really examine it in detail. So, after wrestling with his conscience, he killed the bird.

He spent the next two weeks drawing, studying, and eventually painting the bird. As soon as he finished, he reportedly had a mental breakdown. Not only had he been painting almost nonstop for years at that point, he really didn’t like killing birds. Plus, in the case of the golden eagle, instead of shooting it from a distance, he had killed it up close in person—as humanely as possible, but he still ended its life, and that bothered him.

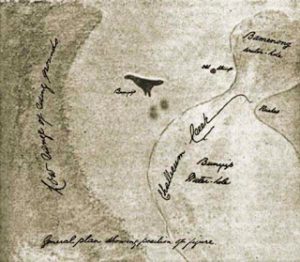

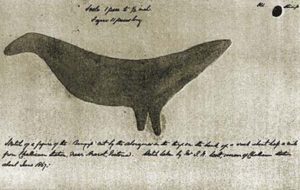

The mystery comes from a detail in the painting’s background. The golden eagle is shown in front of a dramatic background of snowy mountains, with a dead snowshoe hare in its talons. But in a tiny detail in the lower left-hand corner, a man is shown crossing a gorge on a fallen tree trunk. Strapped onto the man’s back is a dead golden eagle.

The man is awkwardly rendered, but experts believe it’s a self-portrait of Audubon himself. Some experts believe Audubon included himself with a dead eagle, navigating a perilous climb, to indicate his emotional struggle in killing the bird. But when the painting was eventually included in Audubon’s famous book of bird illustrations, the figure was gone. The gorge with the fallen tree remains, but the little man carrying the dead bird has been painted out.

The question is why. Who made that decision, Audubon himself or the publisher? If Audubon did it, was it because he was embarrassed that he’d included a self-portrait, or was he embarrassed at the poor rendering of his figure, or did he just think it detracted from the painting, or some other reason? If the publisher did it, did he dislike the badly painted little man, or did Audubon ask him to remove the figure, or some other reason? We don’t know, and very likely we’ll never know.

While Audubon reportedly loved birds, it turns out he wasn’t a great human. Besides shooting a whole lot of birds and other animals, sometimes hundreds in a single day, and lying in published scientific papers, he “owned” enslaved people and reportedly made money selling them. (Just saying that sentence makes me so mad. You cannot own people.) In 2023, members of the National Audubon Society called for the group to change its name and drop any mention of Audubon, and when the board of directors said no, a lot of members resigned.

I came into this topic really hoping Washington’s eagle was a real bird, and believing that James Audubon was an artist who loved birds and was an honest man who made some mistakes. Now I’ve discovered that Audubon was a liar and a bad person, and that Washington’s eagle was probably just the result of one of his lies. At least we still have golden eagles, bald eagles, and lots of other amazing birds to admire!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!