Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:58 — 18.2MB)

Let’s start out the new year with a bona fide mystery animal, the White River Monster from Arkansas! Is it a real animal? If so, is it a known animal or something new to science? If it’s a known animal, what could it be? Lots of questions, maybe a few answers! Happy new year!

Further listening:

The not exactly useful picture supposedly of the White River Monster, taken in 1971:

A northern elephant seal, AKA Mr. Blobby:

A Florida manatee:

A bull shark:

Two bottlenose dolphins:

An alligator gar (below) and a human (above):

Alligator gar WEIRD FISH FACE:

Gulf sturgeon:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

If you’ve listened to the final episode of 2019 last week, you’ll remember it was about some mystery water animals of various kinds. Well, I’ve got another water mystery for you today to start off the new year, the White River monster. I heard about this one in a recent episode of MonsterTalk, which is a great podcast I recommend if you don’t already listen to it.

The White River is in North America, originating in the mountains in northwestern Arkansas and flowing from there through Missouri, then back into Arkansas where it joins the Mississippi River. In 1915 a man near the small town of Newport, in the central Ozarks region of Arkansas, saw an enormous animal with gray skin in the river.

A few other people saw it too, but it wasn’t until July of 1937 that things really heated up. The monster returned, and this time a lot of people saw it. News of it hit the local papers and spread throughout the country, and people started showing up to look for it. Some people came prepared to kill or catch it while others just wanted to see it.

Estimates of the monster’s size varied quite a bit. A man named Bramlett Bateman, who owned a lot of the farmland along that stretch of the river, was quoted in several newspaper articles. He described the monster as being the length of three cars in one article, but in another his estimate was smaller, only 12 feet long, or 3.7 m, and four or five feet wide, or 1.2 to 1.5 meters. But it doesn’t seem that he or anyone else got a really good look at it.

It was described by numerous people as being gray-skinned. Bateman said it had “the skin of an elephant…with the face of a catfish.” I dug into as many original newspaper articles as I could find without actually paying for access to them, and very few of them have a real description of the animal. The only description given in a New York Times article from July 23, 1937 is this:

“Half a dozen eye-witnesses…reported seeing a great creature rise to the surface at rare intervals, float silently for a few minutes and then submerge, making its presence known only by occasional snorts that bubbled up from the bottom.”

Another article quotes Bateman as saying he saw the monster “lolling on the surface of the water.”

Bateman decided he was going to blow the monster up with dynamite. What is it about people whose go-to solution to seeing an unidentified animal is to throw dynamite in the water? The local authorities said, uh no, you cannot just throw dynamite into the river, but other people brought machine guns and other weapons and patrolled the river looking for the monster. A plan to make a giant net and catch the monster petered out when people found out that making and deploying a net that big is expensive and difficult.

The monster was mostly reported in an eddy of the river that stretched for about a mile and was unusually deep, about 60 feet deep, or 18 meters. The river is about 75 feet wide at that point, or 23 meters. The Newport Chamber of Commerce hired a diver from Memphis named Charles B. Brown, who brought an eight-foot harpoon with him when he descended into the river. He didn’t find anything, but the tourists had fun.

Suggestions as to what the monster might be ranged from a sunken boat that sometimes bobbed briefly to the surface to a monstrous catfish. Many people were convinced it was a huge fish of some kind, especially an alligator gar.

Eventually sightings tapered off and the excitement died down until June of 1971, when it started being seen again. Again the size estimates were all over the place, with one witness saying it was the size of a boxcar, which would be about 50 feet long, or 15 meters, and 9 feet wide, or 2.8 meters. Another witness said it was only 20 feet long, or 6 meters. Some witnesses said it had smooth skin that looked like it was peeling all over, had a bone sticking out of its forehead, and it made sounds that one witness described as similar to both a horse’s neigh and a cow’s moo. On July 5, 1971, three-toed tracks 14 inches long, or 36 cm, were also found on an island together with crushed plants that showed a huge animal had come out of the water.

This time, at least, no one tried to dynamite or even net the monster. Instead, in 1973 Arkansas passed a law creating the White River Monster Refuge along that section of the river, to protect the monster. But no one has seen it since.

There is a photo of the monster taken in 1971, but it’s a blurry Polaroid that was reproduced in a newspaper and the original lost. The photo was taken by a man named Cloyce Warren, who was out fishing with two friends. Warren said it had “a spiny ridged backbone and [was] splashing all around.”

So what could the White River Monster be? Is it a misidentified known animal, a completely unknown animal, or just a hoax?

Obviously people are seeing something in that part of the White River. But it’s reportedly so big that if there was a population living anywhere in the river, it would be spotted all the time. So maybe it’s an animal that only sometimes strays into the White River and actually lives in the much larger Mississippi River—or even in the Gulf of Mexico, where it sometimes swims upriver.

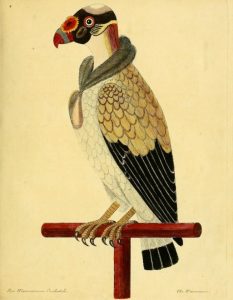

Cryptozoologists and other interested people have made suggestions over the years. One suggestion is that it’s an elephant seal. The northern elephant seal is an enormous animal, although it’s nowhere near 50 feet long. The male is much larger than the female, up to 16 feet long, or 4.8 meters, and bulky with blubber that keeps it warm when diving deeply for food in the Pacific Ocean where it lives.

But wait, the Pacific Ocean? You mean it doesn’t live in the Gulf of Mexico?

Nope, the endangered elephant seal only lives in the Pacific. And the Pacific Ocean is separated from the Gulf of Mexico by a whole lot of the North American continent.

A man named Joe Nickell, who’s a paranormal investigator and who was interviewed on MonsterTalk episode 204, has suggested the White River Monster is a manatee—specifically the Florida manatee, which is a subspecies of West Indian manatee. In the winter it mostly lives around Florida but in summer many individuals travel widely. It’s sometimes found as far north as Massachusetts along the Atlantic coast, and as far west as Texas in the Gulf of Mexico.

The manatee is large, up to 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters, with females being somewhat larger than males. Its skin is gray but since it moves slowly, it can look mottled in color due to algae growing on its skin, and it sometimes also has barnacles stuck to it the way some whales do. It has a pair of front flippers with three or four toenails, no hind legs, and a paddle-like tail. It eats plants and only plants, and is completely harmless to humans, fish, and other animals. Also because it moves slowly and spends a lot of time at the surface, since it’s a mammal and has to breathe air, it’s vulnerable to being injured by boats.

In the 1970s there were only a few hundred manatees alive and it nearly went extinct. It was listed as an endangered species and after a lot of effort by a lot of different conservation groups, it’s now only considered threatened. So while people might recognize a manatee these days, back in the 1970s it was practically unknown everywhere except southern Florida since it was so rare. And in the decades before 1971, people didn’t travel as much and didn’t know much about increasingly rare animals that didn’t live in their particular part of the world.

In other words, it’s completely possible that people from Arkansas would see a manatee in 1915, 1937, and 1971 and not know what it was. But could a manatee really travel that far from the ocean and survive?

The Mississippi River empties into the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana in the United States. Texas is to the west of Louisiana, then Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida to the east. In other words, it’s well within the known range of the Florida manatee. Manatees are known to sometimes travel up the Mississippi. This happened most recently in October of 2016 when a manatee traveled as far as Memphis, Tennessee before it was found dead in a small lake connected to the river. That’s a distance of 720 miles, or 1,158 km, and that was with wildlife officials trying to capture it to return it to the Gulf. That same year a manatee also traveled as far as Rhode Island along the Atlantic coast. Memphis is actually much farther up the Mississippi than the White River is, so if the manatee had branched off into the White River it might have led to new sightings of the White River Monster.

The manatee can live in fresh water perfectly well. One species, the Amazonian manatee, is a fully freshwater animal that never leaves the South American rivers where it lives. But despite its size, the manatee doesn’t have a lot of blubber or fat to keep it warm. The farther away it travels from warm water, the more likely it is to die of cold.

But while an errant manatee might explain some White River Monster sightings, it doesn’t fit with all of them. Other animals from the Gulf of Mexico sometimes find their way up the Mississippi too. It’s a huge river, and since an ocean animal doesn’t understand what a river is, it doesn’t know it’s never going to reach the ocean again unless it turns around. Most marine animals can’t survive for long in fresh water, but some animals, like the manatee, can tolerate fresh water much better. That’s also the case for the bull shark.

In 1937, the same year the White River Monster was spotted for the second time, a five-foot bull shark, or 1.5 meters, was caught in Illinois, which is even farther upstream from the Gulf of Mexico than Tennessee and Arkansas. Bull sharks live throughout much of the world’s oceans in warmer water near coasts and are often found in rivers and lakes, although they don’t live as long in fresh water as they do in salt water. The largest bull shark ever measured was 13 feet long, or 4 meters, so a large one is about the size of a manatee.

Occasionally a dolphin travels up the Mississippi River, but marine dolphins can’t survive for long in fresh water and will die soon if they can’t make their way back to the ocean. A dolphin in fresh water starts to develop skin lesions and then the skin begins to peel, leading to bacterial infection and death. Remember that some witnesses in 1971 described the White River Monster as a gray animal with peeling skin.

Nine different species of dolphin and many species of whale live in the Gulf of Mexico. Of those, only the bottlenose dolphin lives close to the coast and is usually the species that accidentally travels into fresh water and can’t find its way out. The bottlenose dolphin isn’t any larger than the manatee, up to about 13 feet long, or 4 meters.

1971 was an active hurricane year, including the category 5 Hurricane Edith that killed 37 people in mid-September. Marine animals that can travel quickly, like dolphins and sharks, will flee to calmer waters when a hurricane approaches, and while that usually means out to sea, it wouldn’t be out of the question for a frightened dolphin or other large marine animal to make its way into the Mississippi by accident ahead of a hurricane, especially a hurricane as big as Edith.

Another possible identity for the White River Monster is one that was suggested in 1937, the alligator gar. It’s a freshwater fish that lives throughout the Mississippi River and other rivers and lakes in the southern United States and parts of northern Mexico. The alligator gar gets its name because of its toothy jaws, which do resemble an alligator’s, and it can grow up to ten feet long, or 3 meters. It’s a really weird fish and eventually I’ll probably do a full episode on it and its relatives, just as I have a full episode planned about the manatee. It has gills like other fish, but it can also breathe air through its swim bladder, which is lined with lots of blood vessels that absorb oxygen. Every so often an alligator gar will come to the surface and gulp air to replenish the oxygen in its swim bladder, so it would be seen at the surface briefly but periodically as was described by many witnesses. This is also the case for the manatee and dolphin, who breathe air.

The alligator gar is an ambush predator, which means it waits in the water without moving much at all until an animal approaches. Then it shoots forward and grabs it. It mostly eats small fish, invertebrates of various kinds, and waterfowl like ducks.

The final possibility of the White River Monster’s identity is the gulf sturgeon. It’s a subspecies of the Atlantic sturgeon that lives in the Gulf of Mexico, although it’s also known from various rivers in the southeastern United States. The reason it’s found in rivers is that the gulf sturgeon is anadromous [a-NADro-mus], the term for a fish that migrates from the ocean into fresh water to spawn. The salmon is the most famous anadromous fish, which fights its way upriver to spawn and then die. In the case of the gulf sturgeon, it hatches in fresh water and lives there for the first two years or so of its life before making its way downstream to the ocean. Then it returns to freshwater to spawn every spring, usually the same river where it was hatched, and goes back to the ocean in autumn.

The gulf sturgeon fits a lot of the descriptions of the White River Monster sightings. It’s covered with five rows of scutes that project from the back and sides in a sort of low sawtooth pattern, which fits the “spiny ridged backbone” that Cloyce Warren reported seeing in 1971, and its elongated snout has sensory barbels like a catfish, which matches Bramlett Bateman’s 1937 description of the monster having the face of a catfish. It’s gray, gray-green, or brownish in color with a lighter belly, and it can grow up to 15 feet long, or 4.5 meters, although most are about half that length.

The gulf sturgeon usually migrates in groups, but occasionally one can get separated from its group and find its way into a stretch of water by itself. It also doesn’t eat much during the summer when it’s in freshwater. In the winter it lives just off the coast in shallow water, where it’s a bottom feeder. It sucks up invertebrates from the sea floor, feeling for them with their barbels. It gains lots of weight during the winter and then loses it all in the summer. Sturgeons do sometimes jump out of the water, especially in summer–as much as fix feet out of the water. No one’s sure why. Also during the summer, the sturgeon makes a sound like a creaky hinge.

I think it’s probable that the White River Monster sightings are of more than one type of animal, and while we can make an educated guess as to which animals might have been spotted and misidentified, we can’t know for sure. So while at least some of the sightings may have been of a manatee or a gulf sturgeon or another of the animals we talked about today, there’s also the possibility that something else occasionally swims up the Mississippi from the Gulf and into the White River. Hopefully, next time the White River Monster appears, someone gets a really good look at it and some good pictures so we know for sure.

This is what a sturgeon sounds like, by the way:

[sturgeon creaky sound]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!