Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:10 — 16.5MB)

Subscribe: | More

This week we range across the world to solve (sort of) the mystery of the wyvern, the basilisk, the cockatrice, and crowing snakes! Thanks to listener Richard E. for suggesting this week’s topic!

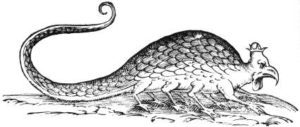

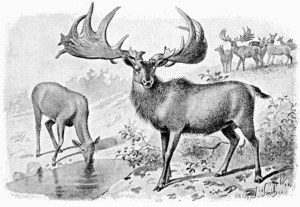

From left to right, or whatever since the three have been confused since at least the middle ages: the basilisk, the cockatrice, and the wyvern:

The king cobra, or maybe the basilisk:

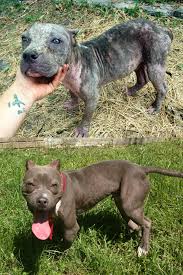

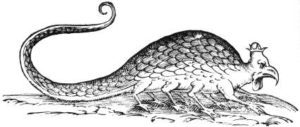

The Egyptian mongoose/ichneumon, or maybe the cockatrice:

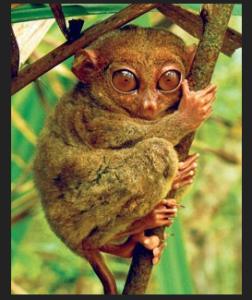

Basilisk!

Further reading:

Extraordinary Animals Revisited by Karl P.N. Shuker

Gode Cookery: The Cockentrice – A Ryal Mete

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode was inspired by listener Richard E., who suggested the wyvern as a topic. He even attached some photos of wyverns in architecture around Leicester, England. I forgot to ask him if he lives in Leicester or just visits the city, but I looked at the photos and was struck by how much the wyvern resembles the cockatrice. Next thing I knew, I was scouring the internet for audio files of howling snakes. It all makes sense by the end.

Before we jump in, I’d like to apologize to a guy named Mike W. who is from Leicester. Mike, if by some crazy coincidence you’re listening, I am so, so sorry for the way I treated you in London in 1996. I was a jerk in my 20s, to put it mildly. You were such a great guy and I have felt awful ever since.

Okay, my oversharing out of the way, let’s talk about wyverns.

The word wyvern is related to the word viper, and originally that’s what it meant, but by the 17th century the word had lost its original meaning and was attached to a heraldic animal instead. The wyvern has been popular in heraldry since the middle ages.

In video games, the wyvern is usually a two-legged dragon with wings. In heraldry, it’s less dragonlike and more snakey, but it almost always has one pair of legs and one pair of wings. Frequently it wears a crown or has some sort of crest, and quite often its head looks a lot like a rooster’s.

The heraldic wyvern doesn’t seem to have ever been considered a real animal, but the cockatrice was. The cockatrice is usually depicted as a snakelike animal with a one pair of legs, one pair of wings, and a rooster-like head. You see the connection. But here’s the really confusing thing. The words cockatrice and basilisk were used more or less interchangeably as early as the 14th century. In fact, in the King James Version of the Bible, Isaiah 14 Verse 29 mentions a cockatrice, while the same verse in the English Revised Version uses the word basilisk instead.

Those two words don’t even sound alike. And if like me you grew up playing Dungeons & Dragons and reading books like Walter Wangerin Jr.’s The Book of the Dun Cow, you think of the cockatrice and the basilisk as totally different animals.

I’m going to talk about the basilisk first. Then I’ll come back to the cockatrice.

The basilisk has an old, old pedigree. A lot of online sources claim that Pliny the Elder was the first to describe the basilisk in his natural history in about 79 CE, but it was already a well-known animal by then. We know because the Roman poet Lucan, who died in 65 CE, makes reference to the basilisk twice in his epic poem Pharsalia in a way that implies his audience was completely with the animal’s supposed abilities.

The basilisk was supposed to be deadly—so deadly, in fact, that if a man on horseback speared a basilisk, the venom would run up the spear and kill not only the rider, but the horse too. That’s one of the stories Lucan references in his poem. Pliny also includes it in his natural history.

All the basilisk had to do was look at you and you’d die or be turned to stone. Birds flying in sight of a basilisk, no matter how high above it they were, would die in midair. The ground around a basilisk’s home was blighted, every plant dead and even the rocks shattered.

So what did the basilisk look like? Pliny describes it this way. I’ve taken this quote from a site called “The Medieval Bestiary,” which has a much clearer translation than Wikipedia’s and other sites that seem to have copied Wikipedia.

“It is no more than twelve inches long [30 cm] and has white markings on its head that look like a diadem. Unlike other snakes, which flee its hiss, it moves forward with its middle raised high.”

In other words, the basilisk was a snake, and not even a big snake. And according to Pliny, the weasel was capable of killing the basilisk. “The serpent is thrown into a hole where a weasel lives and the stench of the weasel kills the basilisk at the same time as the basilisk kills the weasel.”

In other words, someone would pick up a basilisk—which was supposed to be deadly to touch—and toss it down into a weasel’s burrow, and the weasel and the basilisk would both end up dead. Pliny, did you even think about what you were writing?

But back up just a little and the story starts to make more sense. We all saw “Rikki Tikki Tavi” as kids, right? The mongoose does look like a weasel. It’s also resistant to the king cobra’s venom and will prey on it and other snakes. The king cobra has an expandable hood with light-colored false eye spots on it. Its venom is so potent that it can kill a human in half an hour, and one of the final symptoms is paralysis, which may account for reports of the basilisk turning people to stone. King cobras can’t spit their venom, but many other cobras can. And most importantly, the weird notion that the basilisk moves forward with its middle raised high maybe explained by the king cobra’s habit of rearing up when threatened. It can still move forward when its front is raised.

But the king cobra is a big snake. Its average length is about twelve feet [3.7 m] and it can grow as long as 18 feet [5.5 meters]. Pliny describes a snake only a foot long [30 cm]. It’s possible Pliny just wrote the length wrong, conflated the cobra with some smaller snake, or scribes made a mistake copying the original writing. But the idea that the basilisk is actually a cobra seems cemented not by Pliny but by Lucan. Let me quote from book nine of Pharsalia, verses 849 to 853:

“There upreared his regal head

And frighted from his track with sibilant terror

All the subjects swam

Baneful, ere darts his poison. Basilisk.

In sands deserted king.”

A hissing poisonous crowned animal that rears up? It sounds like a king cobra to me. And the fact that stories about the basilisk mention its terrible hissing makes it even more likely.

The king cobra’s hiss sounds more like a growl. It has low-frequency resonance chambers in its windpipe that enhance and deepen the sound of its hiss. Here’s a clip of one, and I would not want to hear this coming from a snake the length of a truck:

[scary hissing]

At some point, though, the basilisk became a more lizard-like animal in western culture and took on rooster-like characteristics. The Venerable Bede, an English monk who lived from about the year 672 to 735, was the first to write down the story of the basilisk as many of us know it today. He said the basilisk was born from an egg laid by an old rooster. Hens do occasionally change sex and take on male characteristics, such as growing a pronounced crest and wattles, long tail feathers, and crowing. Sometimes they stop laying eggs but sometimes they don’t.

Incidentally, the other chickens take all this in stride and do not make a big deal about where the new rooster can go to the bathroom.

Other details got added to the basilisk story over the centuries. Sometimes the egg is described as round and leathery, which is true of many reptile eggs, and sometimes a toad is supposed to brood the egg until it hatches. Sometimes the rooster has to lay the egg at a certain time of year or moon phase. Whatever the circumstances surrounding the egg being laid, the animal that hatches from it is supposed to be a deadly serpent or lizard.

These are all details not described by Pliny. My guess is that the story of a rooster’s egg hatching into a deadly reptile was already a folktale in England when Pliny wrote his Natural History. The stories got conflated, probably by scholars who thought they described the same animal. That might also explain why the word cockatrice got grafted onto the rooster-egg legend. Let’s go back to learn about the cockatrice to figure out how.

The word cockatrice comes from a medieval Latin word that was a translation of the Greek word ichneumon from our old friend Pliny’s Natural History. It’s the same name used for the mongoose, although it can also mean otter. According to Pliny, the ichneumon will fight a snake by first covering itself with several coats of mud and letting it dry to form armor. Pliny also describes the ichneumon as waiting for a crocodile to open its jaws for the little tooth-cleaning birds to enter. When the crocodile falls asleep during the bird’s ministrations, the ichneumon runs down its throat and eats the croc’s intestines, killing it.

So the word that inspired the cockatrice wasn’t a snake at all. It was something that killed snakes and crocodiles. The confusion seems to be etymological. Ichneumon means something like “tracker” from a Greek word I can’t spell, track or footstep. Translated into Latin, it becomes cockatrix [probably spelled wrong] for the word for “tread.” Cockatrice is the corruption of cockatrix. But a cockatrice to English-speaking ears no longer sounds like any kind of snake-killing mammal. It sounds like the word cock, a rooster, combined with a slithery-sounding ending. So it’s very possible the confusion came from the word change mixed with confused tellings of the basilisk story. And when you consider that Chaucer referred to the basilisk as a basilicock, it’s easy to see that English speakers, at least, have been confusing the words and monsters for many centuries.

So it seems we’ve solved this mystery once and for all. The basilisk was a king cobra, the cockatrice was a mongoose, the wyvern was a fanciful heraldic animal, and we’re done.

But wait. Not so fast.

There are widely spread stories of snakes with combs and wattles that can crow like roosters. But those stories aren’t from England. They’re from Africa, with related stories in the West Indies.

The story goes that there’s a snake in east and central Africa that can grow up to twenty feet long [6 meters]. It’s dark brown or gray but has a scarlet face with a red crest that projects forward. Males also have a pair of face wattles and can crow, while females cluck like hens. Supposedly they have deadly venom and will lunge down from trees to attack humans who pass beneath.

At this point I got a little frantic and started trying to find out more about snake sounds. I didn’t think snakes could do anything but hiss, but it turns out that snake vocalizations are a lot more interesting than that.

In addition to the cobra’s deep hiss, bull snakes grunt. That’s how they get their name; they sound a little like cows. And at least one snake makes a sound no one would expect. That’s the Bornean cave racer, Orthriophis taeniurus grabowskyi, native to Sumatra and Borneo. It’s a lovely slender blue snake, not poisonous, also called the beauty ratsnake, and can grow some six feet long [1.8 m]. Some subspecies are kept as pets, but not grabowskyi as far as I know.

The snake has been known to science for a long time, but in 1980, a scientific exploration of the Melinau cave system in Borneo heard an eerie hoarse yowling in the dark, something like a cat. After the scientists no doubt wet their pants, they spotted a beauty ratsnake coiled on the cave floor. It was clearly making the sound.

I tried so hard to find audio of this snake. I really, really wanted to share it. But I’ve had no luck so we’ll just have to imagine it.

Most snakes don’t have vocal cords. That’s the name given to folds of tissue above the larynx. Snakes do have a larynx, and the bull snake, also called the pine snake or gopher snake, and native to the southeastern United States as far north as New Jersey, has a single vocal cord and a well-developed glottis flap. They’re noisy little guys for snakes. They grunt, hiss, and rattle their tails against dead leaves to scare potential predators away. Here’s a sample:

[hissing snake]

There are also stories from all around the world, from every region where snakes live, about snakes mimicking prey to draw it near. The stories come from people from every walk of life who are in position to observe nature closely: farmers, hutners, fishers, explorers—but unfortunately not any scientists. Not yet, anyway. Here’s one of the many examples given in Karl Shuker’s excellent book Extraordinary Animals Revisited, an excerpt I’ve chosen for reasons that will shortly become clear. It’s from an African report from 1856.

“The story of the cockatrice, so common in many parts of the world, is also found among the Demares. But instead of crowing, or rather chuckling like a fowl when going to roost, they say it bleats like a lamb. On its head like the guinea fowl it has a horny protuberance of a reddish color.”

It’s entirely possible that many snakes make sounds that mimic other animals, although whether they do it to lure prey near or whether it’s just a coincidence is another thing. But what about the whole issue about snakes not being able to hear airborne sounds? When I was a kid, I remember reading many books that said snakes can’t hear, they can only detect vibrations from the ground through their jaw bones.

Well, that’s not actually true. Snakes can hear sounds quite well, although their range of hearing is limited compared to mammals. In fact, a survey published in 2003 by the Quarterly Review of Biology confirms that snakes are more sensitive to airborne sounds than they are to ground-borne sounds. So it’s not that ridiculous to imagine a snake that makes sounds people might interpret as crowing or clucking.

But what about the wattles? A lot of snakes have head decorations, including many species of horned vipers that have modified scales above the eyes that really do look like horns. The rhinoceros viper has two or three horns on its nose. I couldn’t find any snakes with wattle-like frills, but it’s not out of the range of possibility. Plus, sometimes snakes don’t fully shed their skins and end up with bits and pieces of old skin left behind, which can stick out from the body.

Whether the African crowing snake legends have anything to do with the European legends of basilisks hatched from rooster eggs, I have no idea. The stories are different enough that I’m inclined to think they’re not related. Then again, reports of crowing snakes might have influenced the basilisk legend.

Incidentally, there’s a real-life lizard given the name basilisk, also called the Jesus lizard because it runs on water to escape predators. It lives in tropic rain forests in Central and South America and can run as fast as seven miles per hour [11 km/hr] on its hind legs, and when it reaches water it just keeps going. It’s big webbed feet and its speed keep it from sinking immediately.

The name ichneumon has been given to a few modern animals too: a type of mongoose that ancient Egyptians believed ate crocodile eggs, and various types of flies and wasps that parasitize caterpillars.

I was hoping that the cockatrice and wyvern would have lent their names to modern real animals too, but I couldn’t find any. But I did find something almost as good. In the middle ages there was a fancy dish called a cockatrice. I found this at a site called “Gode Cookery dot com” where good is spelled g-o-d-e. The site has it listed under cockentrice, with an N. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

Here’s a sample recipe, which the site took a book published in 1888 titled “Two Fifteenth Century Cookery-Books.”

“Take a capon, scald it, drain it clean, then cut it in half at the waist. Take a pig, scald it, drain it as the capon, and also cut it in half at the waist. Take needle and thread and sew the front part of the capon to the back part of the pig, and the front part of the pig to the back part of the capon, and then stuff it as you would stuff a pig. Put it on a spit and roast it, and when it is done, gild it on the outside with egg yolks, ginger, saffron, and parsley juice, and then serve it forth for a royal meat.”

A capon, incidentally, can mean either a castrated rooster or an old rooster. Either way, roast cockatrice sounds better than turducken, and way better than being the guy who has to throw the basilisk into the weasel den.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!