Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:46 — 19.4MB)

Let’s learn about some of the biggest sharks in the sea–but not sharks that want to eat you!

Further reading:

‘Winged’ eagle shark soared through oceans 93 million years ago

Manta-like planktivorous sharks in Late Cretaceous oceans

Before giant plankton-eating sharks, there were giant plankton-eating sharks

An artist’s impression of the eagle shark (Aquilolamna milarcae):

Manta rays:

A manta ray with its mouth closed and cephalic fins rolled up:

Pseudomegachasma’s tooth sitting on someone’s thumbnail (left, photo by E.V. Popov) and a Megachasma (megamouth) tooth on someone’s fingers (right):

The megamouth shark. I wonder where its name came from?

The basking shark, also with a mega mouth:

The whale shark:

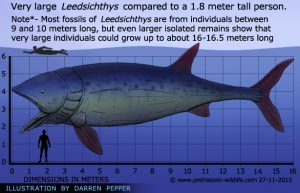

Leedsichthys problematicus (not a shark):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at some huge, weird sharks, but they’re not what you may expect when you hear the word shark. Welcome to the strange world of giant filter feeders!

This episode is inspired by an article in the brand new issue of Science, which you may have heard about online. A new species of shark is described in that issue, called the eagle shark because of the shape of its pectoral fins. They’re long and slender like wings.

The fossil was discovered in 2012 in northeastern Mexico, but not by paleontologists. It came to light in a limestone quarry, where apparently a quarry worker found it. What happened to it at that point isn’t clear, but it was put up for sale. The problem is that Mexico naturally wants fossils found in Mexico to stay in Mexico, and the authors of the study are not Mexican. One of the authors has a history of shady dealings with fossil smugglers too. On the other hand, the fossil has made its way back to Mexico at last and will soon be on display at a new museum in Nuevo León.

Fossils from this quarry are often extremely well preserved, and the eagle shark is no exception. Sharks don’t fossilize well since a shark’s skeleton is made of cartilage except for its teeth, but not only is the eagle shark’s skeleton well preserved, we even have an impression of its soft tissue.

The eagle shark was just slightly shorter than 5 ½ feet long, or 1.65 meters. Its tail looks like an ordinary shark tail but that’s the only ordinary thing about it. The head is short and wide, without the long snout that most sharks have, it doesn’t appear to have dorsal or pelvic fins, and its pectoral fins, as I mentioned a minute ago, are really long. How long? From the tip of one pectoral fin to the other measures 6.2 feet, or 1.9 meters. That’s longer than the whole body.

Researchers think the eagle shark was a filter feeder. Its mouth would have been wide to engulf more water, which it then filtered through gill rakers or some other structure that separated tiny animals from the water. It expelled the water through its gills and swallowed the food.

The eagle shark would have been a relatively slow swimmer. It glided through the water, possibly flapping its long fins slowly in a method called suspension feeding, sometimes called underwater flight. If this makes you think of manta rays, you are exactly correct. The eagle shark occupied the same ecological niche that manta rays do today, and the similarities in body form are due to convergent evolution. Rays and sharks are closely related, but the eagle shark and the manta ray evolved suspension feeding separately. In fact, the eagle shark lived 93 million years ago, 30 million years before the first manta remains appear in the fossil record.

The eagle shark lived in the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow sea that stretched from what is now the Gulf of Mexico straight up through the middle of North America. Because it’s the only specimen found so far, we don’t know when it went extinct, but researchers suspect it died out 65 million years ago at the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs. We also don’t have any preserved teeth, which makes it hard to determine what sharks it was most closely related to. Hopefully more specimens will turn up soon.

Now that we’ve mentioned the manta ray, let’s talk about it briefly even though it’s not a shark. It is big, though, and it’s a filter feeder. If you’ve never seen one before, they’re hard to describe. If it had gone extinct before humans started looking at fossils scientifically, we’d be as astounded by it as we are about the eagle shark—maybe even moreso because it’s so much bigger. Its body is sort of diamond-shaped, with a blunt head and short tail, but elongated fins that are broad at the base but end in drawn-out points.

Manta rays are measured in width, sometimes called a wingspan since their long fins resemble wings that allow it to fly underwater. There are two species of manta ray, and even the smaller one has a wingspan of 18 feet, or 5.5 meters. The larger species can grow 23 feet across, or 7 meters. Some other rays are filter feeders too, all of them closely related to the manta.

The manta ray lives in warm oceans, where it eats zooplankton. Its mouth is wide and when it’s feeding it moves forward with its mouth open, letting water flow into the mouth and through the gills. Gill rakers collect tiny food, which the manta ray swallows. It has a pair of fins on either side of the mouth that are sometimes called horns, but which are properly called cephalic fins. Cephalic just means “on the head.” These fins help direct water into the mouth. When a manta ray isn’t feeding, it closes its mouth just like any other shark, folding its shallow jaw shut. For years I thought it closed its mouth by folding the cephalic fins over it, but that’s not the case, although it does roll the fins up into little points. The manta ray is mostly black with a white belly, but some individuals have white markings on the back and black speckles and splotches underneath. We talked about some mysteries associated with its coloring in episode 96.

The eagle shark isn’t the only filter feeding shark. The earliest known is Pseudomegachasma, the false megamouth, which lived around 100 million years ago. It was only described in 2015 after some tiny shark teeth were found in Russia. The teeth looked like those of the modern megamouth shark, although they’re probably not related. The teeth are only a few millimeters long but that’s the same size as teeth from the megamouth shark, and the megamouth grows 18 feet long, or 5.5 m.

Despite its size, the megamouth shark wasn’t discovered until 1976, and it was only found by complete chance. On November 15 of that year, a U.S. Navy research ship off the coast of Hawaii pulled up its sea anchors. Sea anchors aren’t like the anchors you may be thinking of, the big metal ones that drop to the ocean’s bottom to keep a ship stationary. A sea anchor is more like an underwater parachute for ships. It’s attached to the ship with a long rope on one end, and opens up just like a parachute underwater. The tip of the parachute has another rope attached with a float on top. When the navy ship brought up its sea anchors, an unlucky shark was tangled up in one of them. The shark was over 14 ½ feet long, or 4 ½ m, and didn’t look like any shark anyone had ever seen.

The shark was hauled on board and the navy consulted marine biologists around the country. No one knew what the shark was. It wasn’t just new to science, it was radically different from all other sharks known. Since then, only about 100 megamouth sharks have ever been sighted, so very little is known about it even now.

The megamouth is dark brown in color with a white belly, a wide head and body, and a large, wide mouth. The inside of its lower lip is a pale silvery color that reflects light, although researchers aren’t sure if it acts as a lure for the tiny plankton it eats, or if it’s a way for megamouths to identify each other. It’s sluggish and spends most of its time in deep water, although it comes closer to the surface at night.

The basking shark is even bigger than the megamouth. It can grow up to 36 feet long, or 11 meters. It’s so big it’s sometimes mistaken for the great white shark, but it has a humongous wide mouth and unusually long gill slits, and, of course, its teeth are teensy. It’s usually dark brown or black, white underneath, and while it spends a lot of its time feeding at the surface of the ocean, in cold weather it spends most of its time in deep water. In summer, basking sharks gather in small groups to breed, and sometimes will engage in slow, ponderous courtship dances that involve swimming in circles nose to tail.

But the biggest filter feeder shark alive today, and possibly alive ever, is the whale shark. It gets its name because it is literally as large as some whales. It can grow up to 62 feet long, or 18.8 meters, and potentially longer.

The whale shark is remarkably pretty. It’s dark gray with a white belly, and its body is covered with little white or pale gray spots that look like stars on a night sky. Its mouth is extremely large and wide, and its small eyes are low on the head and point downward. Not only can it retract its eyeballs into their sockets, the eyeballs actually have little armored denticles to protect them from damage. The body also has denticles, plus the whale shark’s skin is six inches thick, or 15 cm.

The whale shark lives in warm water and migrates long distances. It mostly feeds near the surface although it sometimes dives deeply to find plankton. It filters water differently from the megamouth and basking sharks, which use gill rakers. The whale shark has sieve-like filter pads instead. The whale shark doesn’t need to move to feed, either. It can gulp water into its mouth by opening and closing its jaws, unlike the other living filter feeders we’ve talked about so far.

We talked about the whale shark a lot in episode 87, if you want to know more about it.

All these sharks are completely harmless to humans, but unfortunately humans are dangerous to the sharks. Even though they’re all protected, they’re vulnerable to getting tangled in nets, killed by ships running over them, and killed by poachers.

One interesting thing about these three massive filter feeding sharks is their teeth. They all have tiny teeth, but the mystery is why they have teeth at all. Their teeth aren’t just tiny, they have a LOT of teeth, more than ordinary sharks do. It’s the same for the filter feeding rays. They have hundreds of teensy teeth that the animals don’t use for anything, as far as researchers can tell. One theory is that the babies may use their teeth before they’re born. All of the living filter feeders we’ve talked about, including manta rays, give birth to live pups instead of laying eggs. The eggs are retained in the mother’s body while they grow, and she can have numerous babies growing at different stages of development at the same time. The babies have to eat something while they’re developing, once the yolk in the egg is depleted, and unlike mammals, fish don’t nourish their babies through umbilical cords. Some researchers think the growing sharks eat the mother’s unfertilized eggs, and to do that they need teeth to grab hold of slippery eggs. That still doesn’t explain why adults retain the teeth and even replace them throughout their lives just like other sharks. Since all of the filter feeders have teeth although they’re not related, the teeth must confer some benefit.

So, why are these filter feeders so enormous? Many baleen whales are enormous too, and baleen whales are also filter feeders. Naturally, filter feeders need large mouths so they can take in more water and filter more food out of it. As a species evolves a larger mouth, it also evolves a larger body, and this has some useful side effects. A large animal retains heat even if it’s not actually warm-blooded. A giant fish can live comfortably in cold water as a result. Filter feeding also requires much less effort than chasing other animals, so a giant filter feeder has plenty of energy for a relatively low intake of food. And, of course, the larger an animal is, the fewer predators it has because there aren’t all that many giant predators. At a certain point, an adult giant animal literally has no predators. Nothing attacks an adult blue whale, not even the biggest shark living today. Even a really big great white shark isn’t going to bite a blue whale. The blue whale would just bump the shark out of the way and probably go, “HEY, STOP IT, THAT TICKLES.” The exception, of course, is humans, who used to kill blue whales, but you know what I mean.

Let’s finish with a filter feeder that isn’t a shark. It’s not even closely related to sharks. It’s a ray-finned fish that lived around 165 million years ago, Leedsichthys problematicus. Despite not being related to sharks and being a member of what are called bony fish, its skeleton is partially made of cartilage, so fossilized specimens are incomplete, which is why it was named problematicus. Because the fragmented fossils are a problem. I’m genuinely not making this up to crack a dad joke, that’s exactly why it got its name. One specimen is made up of 1,133 pieces, disarticulated. That means the pieces are all jumbled up. Worst puzzle ever. Remains of Leedsichthys have been found in Europe and South America.

As a result, we’re not completely sure how big Leedsichthys was. The most widely accepted length is 50 feet long, or 16 meters. If that’s anywhere near correct, it would make it the largest ray-finned fish that ever lived, as far as we know. It might have been much larger than that, though, possibly as long as 65 feet, or 20 meters.

Leedsichthys had a big head with a mouth that could open extremely wide, which shouldn’t surprise you. Its gills had gill rakers that it used to filter plankton from the water. And we’re coming back around to where we started, because like the eagle shark, Leedsichthys had long, narrow pectoral fins. Some palaeontologists think it had a pair of smaller pelvic fins right behind the pectoral fins instead of near the tail, but other palaeontologists think it had no pelvic fins at all. Because we don’t have a complete specimen, there’s still a lot we don’t know about Leedsichthys.

The first Leedsichthys specimen was found in 1886 in a loam pit in England, by a man whose last name was Leeds, if you’re wondering where that part of the name came from. A geologist examined the remains and concluded that they were part of (wait for it) a type of stegosaur called Omosaurus. Two years later the famous early palaeontologist Othniel Marsh examined the fossils, probably rolled his eyes, and identified them as parts of a really big fish skull.

In 1899, more fossils turned up in the same loam pits and were bought by the University of Cambridge. IA palaeontologist examined them and determined that they were (wait for it) the tail spikes of Omosaurus. Leeds pointed out that nope, they were dorsal fin rays of a giant fish, which by that time had been named Leedsichthys problematicus.

In 1982, some amateur palaeontologists excavated some fossils in Germany, but they were also initially identified as a type of stegosaur—not Omosaurus this time, though. Lexovisaurus. I guess this particular giant fish really has been a giant problem.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!