Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:58 — 13.1MB)

What’s the difference between a snake and a legless lizard? Find out this week and learn about all kinds of interesting reptiles without legs that aren’t actually snakes!

The slow-worm. Not a snake:

Burton’s legless lizard. Not a snake:

The excitable delma. Not a snake:

The Mexican mole lizard. Not a snake or a worm:

The red worm lizard (Amphisbaena alba). Also not a snake or a worm, but honestly, it looks a lot like I imagine the Mongolian death worm to look:

The giant legless skink. Not a snake:

Stacy’s bachia. Not a snake:

Further reading (and this is where I got the Stacy’s bachia picture above):

Bachia lizards–look, no hands!

An Explosive Enigma from Kalmykia—the ‘Other’ Mongolian Death Worm?

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

A couple of weeks ago we discussed the Mongolian death worm and the possibility that it was an animal called an amphisbaenian, which is a reptile without legs that’s not a snake. But there are lots of other legless reptiles that aren’t snakes. So this week we’re going to learn about legless lizards and their friends.

Researchers have determined that leglessness evolved in reptiles many different times in species that aren’t related, often in species that spend at least part of their time underground. If the legs get in the way of burrowing or other movement, over time individuals born without legs or with much smaller legs end up finding more food than those with legs. That means they’re more likely to reproduce, and their offspring may inherit the trait of no legs or smaller legs.

Some legless lizards look so much like snakes at first glance that it can be hard to tell them apart. The common slow-worm, for instance, lives throughout most of Europe and part of Asia. It grows to about a foot and a half long, or 50 cm, and is brown. It mostly eats slugs and worms so it spends most of its time in damp places or underground. But while it looks superficially like a snake, it’s not a snake. It’s a lizard with no legs. Like some other lizard species, including many legless lizards, it can even drop its tail if it’s threatened and then regrows a little tail stump.

So how can you tell the difference between a legless lizard and a snake? The one big clue is if the reptile blinks. Snakes don’t have eyelids; instead, their eyes are protected by a transparent scale that covers the eye completely. Lizards have eyelids and blink. Legless lizards have a different head shape from snakes too, usually more blocky and less flattened. The tongue is not so much forked as just notched, and shorter and less slender than a snake’s tongue.

Species of one family of legless lizards do sometimes have legs. Honestly, this is almost as confusing as the whole deer and antelope mix-up from episode 116. The family is Pygopodidae and they’re actually most closely related to geckos although they don’t look much like geckos. They look like snakes, and to make things even more complicated, geckos and Pygopodids don’t have eyelids. I know I know, I just said lizards have eyelids but geckos are an exception. Pygopodids don’t have front legs at all, but some do have vestigial hind legs that look more like little flaps than actual legs. They’re sometimes called flap-footed lizards as a result. They live in Australia and New Guinea.

One Pygopodid is Burton’s legless lizard, which does actually have vestigial hind legs. It lives in parts of Australia and Papua New Guinea and is kind of a chunky reptile with a pointed nose. It’s brown or gray, sometimes with long stripes, and can grow to more than three feet long, or one meter. It eats other lizards, especially skinks, but will also sometimes eat small snakes.

Burton’s legless lizard mostly stays in leaf litter in forests. Sometimes it will twitch the end of its tail to attract a lizard, which it then grabs by the neck. It will swallow small lizards whole, but if it’s too big to swallow, it will just hold onto its neck until the lizard suffocates or just gives up out of exhaustion. It can also retract its eyes so they’re less likely to be injured if its prey fights back.

The excitable delma is another pygopodid, this one without any legs at all. It lives in many parts of Australia and can grow nearly two feet long, or 54 cm, but almost half that length is tail. It’s shy and nocturnal, so even though it’s very common, it’s seldom seen. It’s brown or grayish with darker stripes on its head. The reason it’s called the excitable delma is because it uses its long tail to jump, twisting and changing directions as it jumps repeatedly up to six inches off the ground, or 15 cm. It does this to escape from predators but it also sometimes just jumps around for the heck of it, according to observations of excitable delmas in captivity. It can also make a squeaky sound. It likes dry, rocky areas and eats insects.

There are other reptiles that look like snakes but aren’t, in addition to the legless lizards. We talked about the amphisbaenians in the Mongolian animals episode a few weeks ago, and also in episode 10. Amphisbaenians are sometimes called worm lizards because they look less like snakes than they do worms. They’re related to both legless lizards and snakes but lost their legs independently.

The amphisbaenian moves like a worm, not a snake. Its skin is loosely attached to its body so that it can move freely, and it bunches up its skin the way a worm bunches up its body, then extends it to move forward or backward. This kind of action is called peristalsis, by the way. Unlike worms, the amphisbaenian has scales because it’s a reptile, but the scales are often arranged in rings that make it look even more like an earthworm. Many amphisbaenians are pink like many earthworms, too.

Most amphisbaenians live underground their entire lives, hunting worms, insect grubs, and other small animals. In most cases they only come to the surface at night or after a heavy rain. Most have no legs at all, but one family consisting of four species, all of them native to Mexico, has little front legs. One of these species is the Mexican mole lizard, which can grow over a foot long, or more than 30 cm. It mostly eats soft-bodied animals like worms and termites, but it will occasionally eat small lizards. It’s pink and has little black dots for eyes and is actually really cute, but don’t let that fool you. If you are a worm, the Mexican mole lizard is a murder machine. It has sharp little teeth that it uses to bite pieces from its prey instead of swallowing them whole.

All the other known amphisbaenians have no legs at all, and for most species we know very little about them. The red worm lizard, for instance, lives throughout much of western South America and appears to be common, but it lives underground and is hardly ever seen. It’s the largest amphisbaenian known and can grow nearly three feet long, or 85 cm, although it’s only a few inches thick, or around 6 cm. It’s brown, reddish, or yellowish in color with a white belly and has tiny eyes that are barely visible. Its tail is blunt and rounded like other amphisbaenian tails, but its tail is tough enough to withstand bites from predators without being injured. If the red worm lizard feels threatened, it raises its head and tail and bends itself into a U shape so that it looks like it has two heads.

That’s why the amphisbaenian has that name, by the way. In ancient mythology, the amphisbaena was a serpent with a head on each end of its body. It was said to mostly eat ants, and that’s actually a good observation of the real amphisbaenian, which often eats ants, termites, and other insects.

Legless skinks are another group of lizards that either have no legs at all or just little flaps instead of hind legs. The males are the ones with the hind leg flaps, which they use to hold onto the female while mating. Most legless skinks look sort of like amphisbaenians, with a blunt-ended tail that’s sometimes hard to tell from the head, but more snakey than wormy for the most part.

One example is the giant legless skink, which is dark gray or black with no legs, and which lives in South Africa. It grows almost a foot and a half long, or 42 cm, and is a little bit of a chonk. We still don’t know much about it but it probably eats insects and other invertebrates like most legless skinks do.

A while back, Llewelly sent me a link to an article about Stacy’s bachia, a lizard that lives in the tropics of South America. It’s a member of the spectacled lizards, which all have lower eyelids that are transparent. That way the lizard can see even if its eyes are closed. I put a link to the article in the show notes if you want to read it.

Stacy’s bachia usually has no hind legs, although it may have little stubby ones, but it hatches with small front legs. But it spends most of its life burrowing in soil and in leaf litter as it hunts termites, ants, and other small animals, and eventually all its legs wear away to nothing.

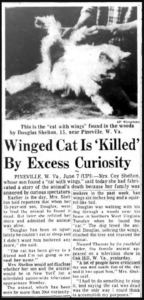

Let’s finish with a mystery animal. Kalmykia is a small region of Russia, and the native people of the area are called Kalmyks. The Kalmyks report that there’s an animal that lives in both the steppes and in sand dunes in the desert that looks like a snake but isn’t a snake, which they actually call the short gray snake. It grows around 20 inches long, or 50 cm, and has smooth skin and a tail that’s short and rounded at the end. It has no legs. This report is from zoologist Karl Shuker’s blog, and check the show notes for a link. The person who told him about this animal also says it’s about six to eight inches thick, or up to 20 cm, so if that’s correct it’s even more of a chonk than the giant legless skink.

Kalmykia is west of Kazakhstan, which is west of Mongolia, so there’s always the possibility that this legless animal is related to or the same animal as the Mongolian death worm that we talked about in episode 156. But Kalmykia is actually pretty far away from Mongolia, and the short gray snake is different from the death worm in two important ways. One, reports say it has no bones. If this is true, it must be some kind of invertebrate, not a reptile. It’s also supposed to move like a worm, although remember that the amphisbaenian does too and it’s a reptile.

But the other thing reported about the short gray snake is much weirder than having no bones. Apparently if someone hits the animal in a particular place on its back—presumably with a stick—it EXPLODES. It explodes into goo that spreads for several feet in every direction, or about a meter, leaving nothing else behind.

It’s possible this isn’t a real animal but a folktale, something like American tall tales about the hoop snake that’s supposed to grab its tail in its mouth and roll itself along like a hoop. The hoop snake is not a real animal, in case you were wondering. There’s no way of telling whether the exploding boneless short gray snake is a real animal, a folktale, or reports of more than one real animal that have gotten mixed up in translation. Hopefully someone who lives in Kalmykia will investigate and find out more. In the meantime, don’t hit any animals with sticks. For one thing, that’s mean. For another, it might explode and leave you covered in goo.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!