Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 28:20 — 28.2MB)

I just adopted two black cats, named Dracula and Poe, so let’s learn about domestic cats! Thanks to RosyWindFox, Nicholas, Richard E., Kim, and an anonymous listener who all made suggestions and contributed to this episode in one way or another!

Further listening:

Weird Dog Breeds – an unlocked Patreon episode

Two beautiful examples of domestic cats (Dracula on left, Poe on right, and it is really hard to photograph a black cat):

The African wildcat, ancestor of the domestic cat:

The blotched tabby (left) and regular tabby (right):

A cat’s toe pads (Poe’s toes, in fact):

The big friendly Maine Coon cat:

The Norwegian forest cat SO FLUFFY:

The surprised-looking Singapura cat:

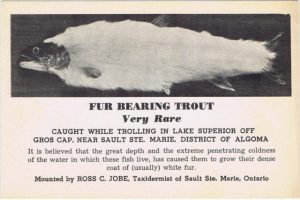

The hairless sphynx breed (with sweater):

The Madagascar forest cat:

The European wildcat:

This came across my feed today and it seemed appropriate, or inappropriately funny depending on your point of view:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I had a different episode planned for this week, but then I adopted two cats, so this week’s episode is going to be about the domestic cat! It also happens to be a suggestion from RosyWindFox after we got to talking about podcasts and animals. Rosy also kindly sent me some research she had done about cats for a project of her own, which was a great help!

But Rosy isn’t the only listener who contributed to this episode. Nicholas suggested weird cats a while back, Richard E. suggested unusual cat breeds, and Kim suggested an episode about domestic cats as invasive species. And we have another suggestion by a listener who wants to remain anonymous about keeping exotic animals as pets, which I thought would fit in well after we talk about invasive species. We’ll also learn about some mystery cats while we’re at it. So buckle up for this big episode about little cats, and thanks to everyone who sent suggestions!

We don’t want to leave the dog lovers out so before we start talking about cats, back in June of 2019 patrons got an episode about strange dog breeds, also suggested by Nicholas. I’ve unlocked that episode so that anyone can listen. There’s a link in the show notes and you can just click the link and listen in your browser, no Patreon login required.

So, most people are familiar with the domestic cat, usually just called a cat. It’s different from the similar-sized felid called a wildcat because it’s actually domesticated. Even domestic cats that have never lived with a human are still part of a species shaped by domestication, so instead of wild cats, wild domestic cats are called feral cats.

Researchers estimate that the domestic cat developed from a species of African wildcat about 10,000 years ago, or possibly as long as 12,000 years ago. This was around the time that many cultures in the Middle East were developing farming, and farming means you need to store grain. If you store grain, you attract mice and other rodents. And what animals famously like to catch and eat rodents? Cats! Wildcats started hanging around farms and houses to catch rodents, and since the humans didn’t want the rodents, they were fine with the cats. Farms that didn’t have any cats had more rodents eating their stored grain, so it was just a matter of time before humans made the next logical step and started taming wildcats so they could trade cats to people who needed them. Besides, wildcats are pretty animals with sleek fur, and if you’ve ever stood by the tiger exhibit in a zoo and wished you could pet a tiger, you will understand how your distant ancestors felt about wildcats.

The species of wildcat is Felis silvestris lybica, the African wildcat, which lives in northern Africa and Southwest Asia. It’s still alive today and looks so much like a domestic cat that it can be hard to tell the species apart, although the African wildcat has long legs and specific markings. For a long time people thought some populations of domestic cats developed from the European wildcat, which we talked about in episode 52, but modern genetic and behavioral studies suggest that all domestic cats are descended from the African wildcat. All wildcat species are pretty closely related, though, and domestic cats and wildcats can and do sometimes interbreed and produce fertile kittens.

The main difference between the African wildcat and the domestic cat is the wildcat’s color. It’s usually a yellowish-gray with lighter belly, with darker stripes and spots. It also has small ear tufts at the tips of the ears.

If you remember episode 106, where we talked about domestication, you’ll remember that some of the wolves that hung around human camps probably initiated domestication. They saw that humans had a pretty sweet deal going and if they alerted those humans to danger and acted nice otherwise, they’d get food. Well, wildcats probably did the same thing. Yes, humans were loud and clumsy and scary, but humans also sometimes gave you food and petted you.

Over many, many generations, the wildcats evolved into cats that didn’t just tolerate humans, they liked humans. It was harder for cats than it was for dogs, though, since canids already lived in packs that were structured similarly to human groups. This is why many people think that dogs are friendlier than cats, because dogs and humans have so many similarities. But cats have adapted really well to human culture.

Wildcats are mostly solitary animals, only coming together during mating season. But domestic cats will live together along with their human family. I adopted my two cats because they get along so well even though they’re not related.

In the olden days people brought cats with them when they moved the same way they took their dogs. The cats were useful to hunt and kill mice that tried to get into the family’s food. People on ships brought cats along for the same reason, because if rats and mice ate the ship’s food stores, the sailors might go hungry. This helped spread cats around the world. In medieval times, cats were so important to sailors that some areas passed laws that a cat had to be onboard a ship for it to set sail.

Egyptian cats were especially in demand, probably because they were more friendly than other cats. So many people wanted Egyptian cats that Egypt passed laws to stop the sale or trade of cats to foreigners, with the oldest law dating to 1700 BCE. But for the most part, cats weren’t selectively bred the way dogs were. Cats were allowed to have babies with whatever mate they chose, which were sometimes wildcats.

It probably wasn’t until about a thousand years ago that humans started taking a real interest in what cats looked like. Until then most domestic cats probably looked a lot like their wild ancestors. But medieval cat owners started selectively breeding cats for particular colors and patterns, such as the blotched tabby pattern. This is a recessive form of the ordinary tabby pattern, which is usually just thin stripes. The blotched tabby is big swirls of color against a paler background. People in the olden days apparently liked the blotched tabby pattern and bred for it.

The domestication of canids, as you may remember from episode 106, usually comes along with behavioral and physical changes. Many dog breeds have puppy-like faces, with a rounder head and shorter jaws. The ears may stay floppy, the tail may have a curl, and coat patterns may change from their wild ancestors’. But this hasn’t really happened in cats, and some researchers think it’s because the cat wasn’t fully domesticated until around 1,000 years ago when this selective breeding started taking place. But cats do show one really interesting adaptation to domestication that wildcats never show. They meow.

Wildcats are usually pretty silent. A wildcat is mostly solitary so it doesn’t need to communicate with pack mates, and it needs to stay quiet so it won’t alert its prey or potential predators. But young cats need to communicate with their mother, which they do by crying and chirping and meowing. Domesticated cats retain this impulse and will talk to humans in the same way that kittens talk to mama cats. Yes, our cats are talking baby talk to us.

If you’re not familiar with the sounds cats make, this is a recording of my cat Poe.

[cat meowing]

Cats don’t just meow and chirp, though. They also purr, as do wildcats and some big cats. We still aren’t sure exactly how cats generate the sound calling purring, but researchers think the cat uses its laryngeal muscles to produce the sound as it breathes in and out. Usually purring denotes relaxation, but a cat may also purr if it’s hurt, stressed, or afraid. Some researchers suggest that the specific frequency of purring vibrations actually promotes the growth of bone and tissue, which helps a cat heal faster if it’s hurt. A cat’s purring is good for people too, acting as a stress reliever.

This is what a purring cat sounds like. This is my cat Dracula purring while I petted him:

[cat purring]

The cat has a rough tongue covered with tiny spines that contain keratin. It uses its tongue to clean and arrange its fur. It has keen hearing, good vision, especially at night, and a good sense of smell. While it can see color, it can’t distinguish between red and green, so if you happen to have red-green color blindness, just reassure yourself that you can see like a cat. The cat can hear into the ultrasonic range, which helps it find rodents which communicate in ultrasound. Some of the noises small kittens make are in the ultrasonic range too, which means most predators can’t hear them but the mama cat can.

If you have a pet cat or have looked closely at a friend’s cat, you’ll know that a cat has whiskers on either side of its nose above its mouth, above its eyes, and some short whiskers on the backs of its legs. All these whiskers are extremely sensitive and help the cat navigate its surroundings in darkness, both by touching things and by reacting to small air currents. You’ll also probably know that a cat’s eyes have slit pupils that react to light. In bright light the pupils contract until they’re practically just a narrow black line. In full darkness they enlarge until the pupils are round, which lets in as much light as possible. Like many nocturnal or largely nocturnal animals, the cat also has a reflective lining in the back of the eye called the tapetum lucidum, which reflects light back through the eye and improves night vision even more. This is why a cat’s eyes seem to shine in the dark.

Cats are climbers, with many adaptations that help it climb. Its claws are retractable, especially its front claws. Most of the time the claws remain inside little sheaths in the toe pads, which keeps them from wearing down and means the cat can walk silently without the claws making tapping noises on hard ground. But when the cat needs to climb, or use its claws as weapons, or if it needs extra traction, it basically flexes its toes to extend the claws. The claws grow directly from the toe bones, not out of skin like our own fingernails do. Another adaptation to climbing is the cat’s keen sense of balance. If a cat falls from a height of at least 3 feet, or about a meter, it’s able to twist its body to land right side up, minimizing its chances of getting injured. Researchers used to think that a cat used its tail to twist around as it fell, but it’s something that even cats without tails can do. A tail helps, but it’s not necessary. The cat’s flexible spine and lack of a collarbone are the real reason it works. Not only that, but a cat’s paw pads act as shock absorbers that also help it land safely.

The cat has four toes on the hind feet and five on the front, with the fifth toe acting as a sort of thumb. A cat has a toe pad for each toe, plus a larger pad in the middle that acts as a sort of palm pad. But if you look closely, the cat also has an extra toe pad on its front feet, farther back from the others. Researchers think this extra pad helps give the paws extra traction if the cat needs it, which helps it control how far it skids or doesn’t skid when it jumps. Basically it’s a brake pad.

Let’s look at a few interesting breeds of cat next. The domestic cat doesn’t have big differences between breeds the way dogs do. I mean, think of how different a Chihuahua is compared to a St. Bernard. But there are differences between cat breeds, of course. The Manx cat and a few other breeds have a genetic mutation that results in a short or missing tail, for instance.

The biggest breed of cat is the Maine Coon, which can grow as big as a bobcat or Eurasian lynx, although without being as heavy as those wild felids. The biggest cat ever measured is a Maine Coon named Barivel, who is 3 feet and 11.2 inches long, or 120 cm, from nose to tail. The Maine Coon has a thick, water-repellent coat that helps it survive in cold weather, and it’s well known for being as friendly as a dog. Genetic studies suggest it developed from the Norwegian forest cat, a breed from northern Europe, which itself may have descended from cats carried on Viking ships around a thousand years ago.

The smallest breed that isn’t due to a form of dwarfism is the Singapura, which is a lightly built cat. I can’t find anything definitive about its height, but it only weighs about eight pounds at most, or 3.6 kg, and usually considerably less. It’s beige with brown ticking that makes it look tan and its eyes are large, which makes it look sort of surprised all the time.

There are a few breeds of cat that are hairless, including the Sphynx. Hairlessness is a mutation that crops up in cats very rarely, and the Sphynx breed was only established in the late 1980s after a few decades of breeding for hairlessness, with the initial attempts resulting in cats with a lot of health issues. The current breed is healthier, but because it doesn’t have any hair it gets cold easily. A lot of owners make sure their cats have warm sweaters to wear in cold weather, which is adorable. Sphynx cats can also get sunburned and need to be bathed to remove dirt and oils from their skin. Some people with cat allergies have found that owning a Sphynx cat actually helped them adapt to cats and reduced their allergic reactions, but others have found that they actually react more strongly to Sphynxes than regular cats. This is because people are allergic not to cat hair but to a protein found in cat saliva and skin glands.

Next, let’s look at a mystery cat from Madagascar. Madagascar is a large island off the coast of Africa, home to lemurs and other animals found nowhere else in the world. It doesn’t have any native felids, although people who live on Madagascar do have pet cats. But a scientist named Michelle Sauther, who researches lemurs, kept seeing cats in the forest. They were all tabbies and the locals called them wildcats, but Dr. Sauther wanted to know more about them.

She and her team set up traps for the forest cats. When they trapped a cat, they took photographs, hair and blood samples, and even dental impressions. Then they released the cats back into the wild. Genetic profiles developed from the samples helped solve the mystery of what these cats are. They’re feral cats descended from ship cats that traveled from areas around the Arabian Sea, hundreds and possibly even a thousand years ago. Enough cats jumped ship on Madagascar to develop into a breeding colony that is still around today.

Dr. Sauther is studying the effects of the feral cats on local animals, because cats can cause a lot of damage as introduced predators. Cats are efficient hunters of small animals, especially rodents like mice, but also birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects, and basically any animal they can catch.

That brings us to the issues caused by feral and pet cats around the world. When people bring cats to parts of the world where cats have never before been, the cats can cause rapid extinctions of small animals. On islands the situation is even worse because an animal’s population may be low to start with and the animal can’t just move to a different area to get away from the cats.

The problem is that people often don’t take care of their cats the way they should. Many people don’t get their cats neutered, which means they have kittens that the owner doesn’t want. Instead of finding good homes for the kittens, the owner will just let the kittens grow up wild outside. Soon there’s a colony of feral cats in the area that have to hunt to survive, and local animals are under much more than ordinary pressure of predation. If the local population of small animals declines because of cats, local predators that also depend on those small animals will decline too, causing a cascade effect that can ruin a local ecosystem.

But it always irritates me when people start acting like cats are horrible animals and people who let their cats outside are horrible people who don’t care about their pets or about wild animals. First of all, cats are cats, and cats are predators. No one can change that. And some cats just cannot be happy inside. My last cat, named Jekyll, had been a stray before I adopted him and he was never happy inside. I tried to make him an inside cat but every time I opened the door to leave he would streak outside, no matter how careful I was. Sometimes I couldn’t get him to come back in. And yes, sometimes he brought me dead or dying birds or animals, including an injured baby bunny once, which always made me feel awful. And after a few years, he was hit by a car and killed.

The safest place for a cat is inside your home, with food and water and a litter box you keep clean. A cat should never be allowed to roam freely, especially at night. Cats are tough animals but they’re also small. Many larger animals see them as prey, not to mention the dangers of cars and contracting diseases from other cats. If your cat isn’t happy being inside all the time, try to limit its outside time to when you can be outside with it, to protect both it and any animals around. Make sure it wears a collar with a bell, too—that’s not a perfect solution, because some cats will learn to walk so carefully that the bell won’t ring, but it will help.

Because of people who don’t neuter their cats and just let them roam around, cats and cat owners have a bad reputation among conservationists. Try to understand that the people who talk about how many birds are killed by cats every year aren’t blaming you specifically, although sometimes it feels that way, I know. They’re blaming the irresponsible cat owners and taking their frustration out on all cat owners.

It’s a complicated issue and as you can tell, I’m ambivalent. On the one hand, I absolutely agree that cats are horrible for local wild animal populations. On the other hand, the people who are loudest and angriest about cats killing birds and other animals don’t think twice about driving a car. One figure I found estimates that a million animals are killed by cars every single day in the United States alone, but then again, cats kill even more animals every day. But most of those animals are killed by feral cats, not pet cats. All we can do is be responsible cat owners and do our best to protect both our pets and the wild animals that live near us.

My newly adopted cats are both definitely inside cats. If a mouse comes into the house they can do their job, but otherwise they’re just going to be pouncing on toy mice.

So that leads us to our final topic suggestion, about the ethics of keeping exotic animals as pets. If this seems a little out there for an episode about domestic cats, remember that it wasn’t all that long ago that domestic cats were wildcats, and that they’re still so closely related to wildcats that wildcats and domestic cats can interbreed. Wildcats and domestic cats still look a whole lot alike too. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to scoop up a wildcat and take it home as a pet. But that’s what some people do.

There’s a TV show out now called Tiger King that people are talking about. I haven’t seen it because I just don’t watch TV, but it sounds pretty horrible. From what I gather, the tigers and other animals aren’t properly taken care of and the people who own the animals aren’t very nice. Generally, the kind of people who want an exotic pet are not the kind of people who bother to learn how to properly take care of it. They figure a tiger is just a big cat and they know how to take care of a cat, but that’s not the case at all.

Even if you get a wild animal as a baby and raise it the same way you would a kitten or puppy, it’s still wild. That means that no matter how sweet it was as a baby, once it’s grown, it considers its own needs first and yours second, if at all. It doesn’t consider itself part of the family group and can be unpredictable and dangerous, no matter how well you think you know its personality. In 2011 a mountain lion kept as a pet in Texas grabbed a four-year-old boy through the bars of its cage and mauled him. Fortunately the boy was okay, but the mountain lion was killed by animal control officers, who had already cited the owner for not providing a bigger cage with smaller gaps between bars. It also turned out that the mountain lion’s owner didn’t have a permit to keep it.

Even smaller felids can be dangerous. Many people keep servals as exotic pets, because they look and act a lot like domestic cats but are exotically spotted. The serval lives in parts of Africa and is a little larger than the domestic cat, with long legs and a small head. We’ve talked about the serval before in episode 52. In late 2019 a man in Ohio apparently let his pet serval out to wander the neighborhood, and it attacked one of his neighbor’s dogs. Again, the serval was killed and the owner fined. In both those examples, the animal wasn’t properly taken care of and ended up being killed, which is sad. It’s always the exotic pet that is miserable, often unhealthy, and usually killed when it does something wrong.

So no, I don’t think anyone should keep a wild animal as a pet. If you just really really love wild animals and want to work with them directly, there are lots of appropriate ways you can do it. You can become a zookeeper or exotic animal veterinarian, a scientist or conservationist who studies wild animals, or a photographer who specializes in photographing animals in the wild. All those suggestions are better for you and for the animals than trying to keep a wild animal as a pet.

This is already a really long episode, but let’s finish up with another mystery so I don’t finish the episode by lecturing everyone. You may remember from episode 52 that we talked about the European wildcat that still lives in Europe and Scotland. The Scottish wildcat is critically endangered, with probably no more than around four hundred animals living in Scotland. But there have been reports going back centuries of a wildcat living in Ireland.

The European wildcat did once live in Ireland, but it died out around 3,000 years ago. It’s also been extinct in England since the 1860s. But reports dating to at least the early 19th century in various parts of Ireland indicate that many people saw and even killed large wildcats—but they didn’t look like the European wildcat. They looked more like the African wildcat.

The most obvious difference between the European and the African wildcat is the tail. The African wildcat’s tail looks like a domestic cat’s tail, relatively thin at the end with a slightly pointed tip. The European wildcat’s tail fluffs out at the end instead of tapering. At least one expert from the 19th century proclaimed that the wildcat sightings in Ireland were actually of hybrids of domestic cats and European wildcats. But remember, the European wildcat had gone extinct in Ireland some 3,000 years before. Besides, these animals were reportedly larger and heavier than domestic cats, and feral cats are usually relatively small.

These large cats are still occasionally spotted in Ireland, with a flurry of sightings as recently as 2002. It’s possible people are just mistaking unusually large feral cats for wildcats, but there’s always the possibility that European wildcats still survive in Ireland, but have hybridized with domestic cats so much that its descendants resemble the African wildcat more than the European wildcat. So if you are a mouse who lives in Ireland, watch out.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes for as little as one dollar a month.

Thanks for listening!