Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:11 — 13.6MB)

Thanks to Conner, Tim, Stella, Cillian, Eilee, PJ, and Morris for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Extinct Hippo-Like Creature Discovered Hidden in Museum: ‘Sheer Chance’

The golden lion tamarin has very thin fingers and sometimes it’s rude:

The golden lion tamarin also has a very long tail:

The cotton-top tamarin [picture by Chensiyuan – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=153317160]:

The pangolin is scaly:

The pangolin can also be round:

The East Siberia lemming [photo by Ansgar Walk – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52651170]:

An early painting of a mammoth:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at some mammals suggested by Conner, Tim, Stella, Cillian, Eilee, PJ, and Morris. Let’s jump right in, because we have a lot of fascinating animals to learn about!

We’ll start with suggestions by Cillian and Eilee, who both suggested a monkey called the tamarin. Tamarins live in Central and South America and there are around 20 species, all of them quite small.

Cillian specifically suggested the golden lion tamarin, an endangered species that lives in a single small part of Brazil. It has beautiful golden or orange fur that’s longer around the face, like a lion’s mane but extremely stylish. Its face is bare of fur and is gray or grayish-pink in color, with dark eyes and a serious expression like it’s not sure where it left its wallet. It grows about 10 inches long, or 26 cm, not counting its extremely long tail.

The golden lion tamarin spends most of its time in trees, where it eats fruit, flowers, and other plant material, along with eggs, tree frogs, insects, and other small animals. It has narrow hands and long fingers to help it reach into little tree hollows and crevices where insects are hiding, but if it can’t reach an insect that way, it will use a twig or other tool to help.

The golden lion tamarin lives in small family groups, usually a mated pair and their young children. A mother golden lion tamarin often has twins, sometimes triplets, and the other members of her family help take care of the babies.

Because the golden lion tamarin is endangered, mainly due to habitat loss, zoos throughout the world have helped increase the number of babies born in captivity. When it’s safe to release them into the wild, instead of only releasing the young tamarins, the entire family group is released together.

Eilee suggested the cotton-top tamarin, which lives in one small part of Colombia. It’s about the same size as the golden lion tamarin, but is more lightly built and has a somewhat shorter tail. It’s mostly various shades of brown and tan with a dark gray face, but it also has long white hair on its head. Its hair sticks up and makes it look a little bit like those pictures of Einstein, if Einstein was a tiny little monkey.

Like the golden lion tamarin, the cotton-top tamarin lives in small groups and eats both plant material and insects. It’s also critically endangered due to habitat loss, and it’s strictly protected these days.

Next, both Tim and Stella suggested we learn about the pangolin. There are eight species known, which live in parts of Africa and Asia.

The pangolin is a mammal, but it’s covered in scales except for its belly and face. The scales are made of keratin, the same protein that makes up fingernails, hair, hooves, and other hard parts in mammals. When it’s threatened, it rolls up into a ball with its tail over its face, and the sharp-edged, overlapping scales protect it from being bitten or clawed. It has a long, thick tail, short, strong legs with claws, a small head, and very small ears. Its muzzle is long with a nose pad at the end, it has a long sticky tongue, and it has no teeth. It’s nocturnal and uses its big front claws to dig into termite mounds and ant colonies. It has poor vision but a good sense of smell.

Some species of pangolin live in trees and spend the daytime sleeping in a hollow tree. Other species live on the ground and dig deep burrows to sleep in during the day. It’s a solitary animal and just about the only time adult pangolins spend time together is when a pair comes together to mate. Sometimes two males fight over a female, and they do so by slapping each other with their big tails.

Unfortunately for the pangolin, its scales make it sought after by humans for decoration. People also eat pangolins. Habitat loss is also making it tough for the pangolin. All species of pangolin in Asia are endangered or critically endangered, while all species of pangolins in Africa are vulnerable. Pangolins also don’t do well in captivity so it’s hard for zoos to help them.

Next, Conner wants to learn about the lemming, a rodent that’s related to muskrats and voles. Lots of people think they know one thing about the lemming, but that thing isn’t true. We’ll talk about it in a minute.

The lemming grows up to 7 inches long, or 18 cm, and is a little round rodent with small ears, a short tail, short legs, and long fur that’s brown and black in color. It eats plant material, and while it lives in really cold parts of the northern hemisphere, including Siberia, Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland, it doesn’t hibernate. It just digs tunnels with cozy nesting burrows to warm up in, and finds food by digging tunnels in the snow.

Lemmings reproduce quickly, which is a trait common among rodents, and if the population of lemmings gets too large in one area, some of the lemmings may migrate to find a new place to live. In the olden days people didn’t understand lemming migration. Some people believed that lemmings traveled through the air in stormy weather and that’s why a bunch of lemmings would suddenly appear out of nowhere sometimes. They’d just drop out of the sky. Other people were convinced that if there were too many lemmings, they’d all jump off a cliff and die on purpose, and that’s why sometimes there’d be a lot of lemmings, and then suddenly one day not nearly as many lemmings.

Many people still think that lemmings jump off cliffs, but this isn’t actually true. They’re cute little animals, but they’re not dumb.

Next, let’s learn about two extinct animals, starting with PJ’s suggestion, the woolly mammoth. We actually know a lot about the various species of mammoth because we have so many remains. Our own distant ancestors left cave paintings and carvings of mammoths, we have lots of fossilized remains, and we have lots of subfossil remains too. Because the mammoth lived so recently and sometimes in places where the climate hasn’t changed all that much in the last 10,000 years, namely very cold parts of the world with deep layers of permafrost beneath the surface, sometimes mammoth remains are found that look extremely fresh.

The woolly mammoth was closely related to the modern Asian elephant, but it was much bigger and covered with long fur. A big male woolly mammoth could stand well over 11 feet tall at the shoulder, or 3.5 meters, while females were a little smaller on average. It was well adapted to cold weather and had small ears, a short tail, a thick layer of fat under the skin, and an undercoat of soft, warm hair that was protected by longer guard hairs. It lived in the steppes of northern Europe, Asia, and North America, and like modern elephants it ate plants. It had long, curved tusks that could be over 13 feet long, or 4 meters, in a big male, and one of the things it used it tusks for was to sweep snow away from plants.

The woolly mammoth went extinct at the end of the last ice age, around 11,000 years ago, although a small population remained on a remote island until only 4,000 years ago.

Our last animal this week is Morris’s suggestion, and it’s actually not a single type of animal but a whole order. Desmostylians were big aquatic mammals, and the only known order of aquatic mammals that are completely extinct.

When you think of aquatic mammals, you might think of whales, seals, and sea cows, or even hippos. Desmostylians didn’t look like any of those animals, and they had features not found in any other animal.

Desmostylians lived in shallow water off the Pacific coast, and fossils have been found in North America, southern Japan, parts of Russia, and other places. They first appear in the fossil record around 30 million years ago and disappear from the fossil record about 7 million years ago. They were fully aquatic animals that probably mostly ate kelp or sea grass, similar to modern sirenians, which include dugongs and manatees.

Let’s talk about Paleoparadoxia to find out roughly what Desmostylians looked and acted like. Paleoparadoxia grew about 7 feet long, or 2.15 meters, and had a robust skeleton. It had short legs, although the front legs were longer and its four toes were probably webbed to help it swim. It probably acted a lot like a sirenian, walking along the sea floor to find plants to eat. Its nostrils were on the top of its nose so it could take breaths at the surface more easily, and it had short tusks in its mouth, something like modern hippos. It may have looked a little like a hippo, but also a little like a dugong, and possibly a little like a walrus.

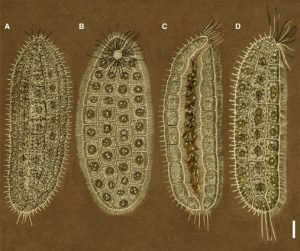

One really strange thing about Desmostylians in general are their teeth. No other animals known have teeth like theirs. Their molars and premolars are incredibly tough and are made up of little enamel cylinders. The order’s name actually means “bundle of columns,” referring to the teeth, and the bundles point upward so that the tops of the columns make up the tooth’s chewing surface. Actually, chewing surface isn’t the right term because Desmostylians probably didn’t chew their food. Scientists think they pulled plants up by the roots using their teeth and tusks, then used suction to slurp up the plants and swallow them whole.

We still don’t know very much about Desmostylians. Scientists think they were outcompeted by sirenians, but we don’t really know why they went extinct. We don’t even know what they were most closely related to. They share some similarities with manatees and elephants, but those similarities may be due to convergent evolution. Then again, they might be related. Until we find more fossils, the mysteries will remain.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, corrections, or suggestions, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com.

Thanks for listening!