Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:49 — 13.0MB)

Thanks to Alexandra, Jayson, and Eilee for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

The nomenclatural status of the Alula whale

Field Guide of Whales and Dolphins [1971]

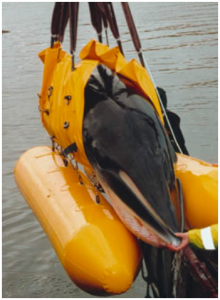

The little Benguela dolphin [photo taken from this site]:

The spinner dolphin almost looks like it has racing stripes [photo by Alexander Vasenin – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25108509]:

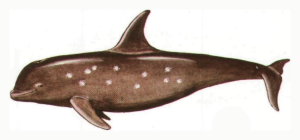

The Alula whale, which may or may not exist:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s learn about some whales and dolphins, including an ancient whale and a mystery whale, all of them really small. Thanks to Alexandra, Eilee, and Jayson for their suggestions!

Let’s start with an ancient whale, suggested by Jayson. The genus Janjucetus has been known since its first species was described in 2006, after a teenage surfer in Australia discovered the fossils in the late 1990s. It grew to about 11 feet long, or 3.5 meters, and lived about 25 million years ago. So far it’s only been found around Australia. But much more recently, just a few months ago as this episode goes live, a new species was described. That’s Janjucetus dullardi, also found in Australia along the same beach where the first Janjucetus species was found, and dating to around the same time period.

We don’t know a lot about the newly described whale, since it’s only known from some teeth and partial skull. Scientists think the individual was a juvenile and estimate it was only around 6 feet long when it died, or 2.8 meters. Small as it was, it would have been a formidable hunter when it was alive. Its broad snout was shaped sort of like a shark’s and it had strong, sharp teeth and large eyes.

Because it was an early whale, it wouldn’t have looked much like the whales alive today. It might even have had tiny vestigial back legs. Its eyes were huge in proportion to its head, about the size of tennis balls, and it probably relied on its eyesight to hunt prey because it couldn’t echolocate.

Its serrated teeth and strong jaws indicate that it might have hunted large animals, but some scientists suggest it could also filter feed the same way a crabeater seal does. Modern crabeater seals have similar teeth as Janjucetus, as do a few other seals. The projections on its teeth interlock when the seal closes its mouth, so to filter feed the seal takes a big mouthful of water, closes its teeth, and uses its tongue to force water out through its teeth. Amphipods and other tiny animals get caught against the teeth and the seal swallows them.

If Janjucetus did filter feed, it probably also hunted larger animals. Otherwise its jaws wouldn’t have been so strong or its teeth so deeply rooted. But Janjucetus wasn’t related to modern toothed whales. While it wasn’t a direct ancestor of modern baleen whales, it was part of the baleen whale’s family tree. Baleen whales, also called mysticetes, have baleen plates made of keratin instead of teeth. After the whale fills its mouth with water, it closes its jaws, pushes its enormous tongue up, and forces all that water out through the baleen. Any tiny animals like krill, copepods, small squid, small fish, and so on, get trapped in the baleen. It’s just like the crabeater seal, but really specialized and way bigger.

Whether or not Janjucetus could and did filter feed doesn’t really matter, because the fact that it’s an ancestral relation of modern baleen whales but it had teeth helps us understand more about modern whales.

Next, Eilee wanted to learn about the Benguela [BEN-gull-uh] dolphin, also called Heaviside’s dolphin. It lives only off the southwestern coast of Africa, and it’s really small, only a little over 5 and a half feet long at the most, or 1.7 meters. It’s dark gray with white markings, with a blunt head that’s almost cone-shaped and a triangular dorsal fin.

The Benguela dolphin is named for its ecosystem. The Benguela current flows northward along the coast, bringing cold, nutrient-rich water up from the depths, which attracts lots of animals. The dolphin lives in relatively shallow water and mainly eats fish and octopuses that it finds on or near the sea floor.

The Benguela dolphin lives in social groups and sometimes hangs out with other species of dolphin. It doesn’t travel very far throughout the year, barely more than 50 miles, or 80 km. When it hunts for food, it uses very high-pitched navigation clicks that orcas can’t hear, but when it’s in safe areas, socializing without any predators around, it communicates and navigates with lower-pitched sounds. Sharks also sometimes attack it and sometimes humans will catch and eat one, but for the most part, it lives a pretty stress-free life just hanging out with its friends and eating little fish. And that’s basically all we know about this little dolphin.

Alexandra wanted to hear about the spinner dolphin, which is common in warmer waters throughout the world. It’s called the spinner dolphin because it likes to leap into the air, spinning around as it does like an American football, which is pretty spectacular. No one except the spinner dolphin is completely sure why it spins, but scientists speculate it serves more than one purpose. The activity takes a lot of energy, so it might be a way to signal to other dolphins that it’s really strong and fit. The big splash when it lands on its side may be a way to communicate with other dolphins. The action might also help dislodge parasites like remora fish that really do attach themselves to bigger, faster animals to hitch rides and incidentally steal food.

Whatever the reason, the spinner dolphin is one of the most acrobatic dolphins in the world. It not only spins, but it jumps around, flips, slaps its tail on the water, and basically acts like a kid on the first swimming pool visit of the summer. Like most dolphins and whales, it’s a social animal, hanging out with friends, family, and sometimes other dolphin species. It eats small animals like fish, squid, and crustaceans, and at least some populations are nocturnal so they can hunt animals that migrate to shallower water at night.

The spinner dolphin is actually pretty small, growing to not quite 7 feet long at most, or 2.4 meters. It’s mainly dark gray on top, lighter gray on the sides, and pale gray or white on its belly.

Let’s finish with our mystery whale or dolphin, called the Alula whale because it was sighted near the town of Alula, Somalia at some time prior to the early 1970s. In 1971 a Dutch sea captain reported that he had seen these whales on multiple occasions, in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. But although it’s a distinctive-sounding whale or dolphin, its existence hasn’t been verified.

Captain Willem Mörzer Bruyns, whose name I have mispronounced, described the Alula whale as being similar in size and shape to the orca or pilot whale, with a tall dorsal fin and rounded forehead. It was sepia brown all over, though, except for white scars all over its body that were shaped sort of like stars. He reported seeing small groups of these whales, anywhere from 4 to 8 of them, traveling together on at least four occasions. He estimated the whales were up to 24 feet long, or 7.2 meters.

There’s quite a bit of confusion about this mystery whale spread across the internet. Some sites I looked at mentioned a book written by Mörzer Bruyns called Field Guide of Whales and Dolphins, published in 1971, but quoted a different book, A World Guide to Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises published in 1981 by Donald S. Heintzelman.

Let me quote the relevant paragraphs from the 1971 book, the original:

“At first encounter a school of 4 approached the ship head on and seeing the dorsal fins the author thought they were [orcas]. When they passed the ship at a distance of less than 50 yards just under the surface in the flat calm, clear sea, it was obvious that this was a different species. … These dolphins were seen in the area during crossings in April, May, June and September, usually swimming just under the surface with the dorsal fin above the water. One duty officer reported he observed them chasing a school of smaller dolphins, who tried to escape. There is, however, a possibility that both species were chasing the same prey.”

If you go to Wikipedia to read about the Alula whale, as of mid-November 2025, it states that the dorsal fin was about 6 and a half feet tall, or 2 meters. But Mörzer Bruyns reported that the dorsal fin was 2 feet tall, or about 60 cm. That’s an important difference. Orcas, AKA killer whales even though they’re actually big dolphins, are distinctively patterned with black and white, and a male orca can have a dorsal fin up to 6 feet tall, or 1.8 meters, while a female’s is typically less than half that height. The pilot whale is also a dolphin, despite its name, but it has a relatively small dorsal fin and is black, dark gray, or sometimes brown. Some researchers suggest that Mörzer Bruyns misidentified pilot whales as something mysterious, but the details he provided don’t really match up.

There are a lot of little-known whales alive today, some only discovered in the last few decades. It’s possible that the Alula whale really is a very rare small whale or dolphin. It’s not clear from his report, but it sounds like Mörzer Bruyns saw the whales on several occasions in the same year. If so, maybe the Alula whale doesn’t actually live in that part of the ocean most of the time, and Mörzer Bruyns saw the same small group several times that just happened to have traveled to the Indian Ocean that year. Maybe no one else has seen them because they’re all living in some remote part of the ocean where humans seldom travel. Hopefully someone will spot one soon.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!