Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:06 — 12.2MB)

Thanks to Fleur, Yuzu, and Richard from NC for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

World’s rarest parrot, extinct in wild, hatches at zoo

This Parrot Stood 3 Feet Tall and Ruled the Roost in New Zealand Forests 19 Million Years Ago

The magnificent palm cockatoo:

The gigantic kakapo:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have a bird episode, specifically some interesting parrots. Thanks to Fleur, Yuzu, and Richard from NC for their suggestions!

Parrots are intelligent, social birds that are mostly found in tropical and subtropical parts of the world, but not always. Most parrots eat plant material exclusively, especially seeds, nuts, and fruit, but some species will eat insects and other small animals when they get the chance. Most parrots are brightly colored, but again, not always. And, unfortunately, most parrot species are endangered to some degree due to habitat loss, hunting for their feathers and for the pet trade, and introduced predators like cats and rats.

All parrots have a curved beak that the bird uses to open nuts and seeds, but which also acts as a tool or even a third foot when it’s climbing around in trees. All parrots have strong clawed feet that they also use to climb around and perch in trees, and to handle food and tools.

Let’s start with Yuzu’s suggestions, the cockatoo and the parakeet. A parakeet is a small parrot, but it’s a term that refers to a lot of various types of small parrots. This includes an extinct bird called the Carolina parakeet.

It was small parrot that was common throughout a big part of the United States. It had a yellow and orange head and a green body with some yellow markings, and was about the size of a mourning dove or a passenger pigeon. Its story of extinction mirrors that of the passenger pigeon in many ways. The Carolina parakeet lived in forests and swamps in big, noisy flocks and ate fruit and seeds, but when European settlers moved in, turning forests into farmland and shooting birds that were considered pests, its numbers started to decline. In addition, the bird was frequently captured for sale in the pet trade and hunted for its feathers, which were used to decorate hats.

By 1860 the Carolina parakeet was rare anywhere except the swamps of central Florida, and by 1904 it was extinct in the wild. The last captive bird died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, which was not only the same zoo where the last passenger pigeon died in 1914, it was the same cage. It was declared extinct in 1939.

The parakeet Yuzu is probably referencing is the budgie, or budgerigar. It’s the one that’s extremely common as a pet, and it’s native to Australia. In the wild it’s green and yellow with black markings, but the domestic version, which has been bred in captivity since the 1850s, can be all sorts of colors and patterns, including various shades of blue, yellow all over, white, and piebald, meaning the bird has patches of white on its body.

The budgie can learn to repeat words and various sounds, especially if it’s a young bird. I had two parakeets as a kid, named Dandelion and Sky so you can guess their colors, and neither learned to talk although I really tried to teach them. Some birds just aren’t interested in mimicry, while others won’t stop, especially if they get attention when they speak.

In the wild, budgies live in flocks that will travel long distances to find food and water. The birds mostly eat grass seeds, especially spinifex, but will sometimes eat wheat, especially in areas where farmland has destroyed much of their wild food. They’re social birds that are sometimes called lovebirds, although that’s the name of a different type of bird too, because they will preen and feed their mates.

Like many birds, the parakeet can see ultraviolet light, and their feathers glow in UV light. This makes them even more attractive to potential mates, as if the parakeet wasn’t beautiful enough to start with.

Yuzu also asked about the cockatoo. There are 21 species of cockatoo, also native to Australia and other nearby places, including Indonesia and New Guinea. It’s much larger than the budgie and most species have a crest of some kind. It lives in flocks and eats various types of plant material, including flowers and roots, but it will also eat insects. The cockatoo isn’t as brightly colored as many parrots, and is usually black, white, or gray, often with patches of color on the crest, cheeks, or tail.

The pink cockatoo is white with pale salmon pink markings on the body, and brighter pink and yellow on its crest. The sulphur-crested cockatoo is white with pale yellow on the undersides of the wings and tail, and a bright yellow crest. We talked about the palm cockatoo in episode 23 because not only does it look like it should be a drummer of the Muppet Animal variety, since it’s black with red cheeks and a big messy crest, it does actually use sticks and nuts to drum against tree branches, to attract a mate.

Richard from NC suggested we learn about Spix’s macaw, also called the blue macaw, because it’s considered one of the world’s rarest parrots. In fact, it was declared extinct in the wild in 2019. It only survives at all because of intensive conservation efforts, including a captive breeding program spread over multiple zoos.

The blue macaw is native to one small part of Brazil in South America, although it used to be much more common several hundred years ago. It’s blue with a gray-blue head. It’s such a beautiful parrot that it was driven to extinction by people trapping the birds to sell as pets, even though that had been outlawed by Brazil, although its numbers had been falling for centuries due to habitat loss. It relied on a particular species of tree called the tree of gold, because its flowers are bright yellow. The blue macaw nested in these trees, and its seedpods were one of its main foods. As groves made up of the tree of gold were chopped down to make way for farmland and towns, the bird became more and more rare.

Luckily, even though the blue macaw doesn’t breed very quickly in captivity, by 2022 there were enough healthy young birds to release twenty into the wild. Just a few weeks ago as this episode goes live, another egg has hatched in captivity in a bird conservation center in Belgium, after the previous hundred eggs were infertile and never hatched.

Next, Fleur wanted to learn more about the kakapo, a flightless, nocturnal parrot that lives only in New Zealand. We talked about it in episode 313, but it’s definitely time to revisit it.

The kakapo is the largest living parrot. It has green feathers with speckled markings, blue-gray feet, and discs of feathers around its eyes that make its face look a little like an owl’s face. That’s why it’s sometimes called the owl parrot. Males are almost twice the size of females on average. It can grow over two feet long, or 64 cm, and can weigh as much as 9 lbs, or about 4 kg. That’s way too heavy for it to fly, but its legs are short but strong and it will jog for long distances to find food. It can also climb really well, right up into the very tops of trees. It uses its strong legs and its large curved bill to climb. Then, to get down from the treetop more efficiently, the kakapo will spread its wings and parachute down, although its wings aren’t big enough or strong enough for it to actually fly. A big heavy male sort of falls in a controlled plummet while a small female will land more gracefully.

The kakapo evolved on New Zealand where it had almost no predators. A few types of eagle hunted it during the day, which is why it evolved to be mostly nocturnal. Its only real predator at night was one type of owl. As a result, the kakapo was one of the most common birds throughout New Zealand when humans arrived.

But by the end of the 19th century, the kakapo was becoming increasingly rare everywhere. By 1970, scientists worried that the kakapo was already extinct. Fortunately, a few of the birds survived in remote areas. Several islands were chosen as refuges, and all the kakapos scientists could find were relocated to the islands, 65 birds in total. While the kakapo is doing a lot better now than it has in decades, it’s still critically endangered. The current population is 237 individuals according to New Zealand’s Department of Conservation.

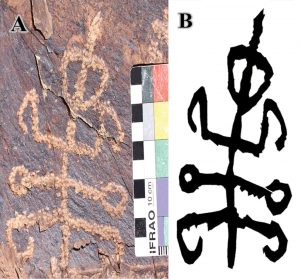

The kakapo may be the largest living parrot, but it’s not the largest parrot that ever lived. That would be the giant parrot. It’s known only from a few fossils dated to between 16 and 19 million years ago, but from those fossils scientists estimate that the giant parrot grew around 3 feet tall, or almost a meter, and possibly weighed almost twice what the kakapo weighs. It’s the largest parrot that ever lived as far as we know, and it was probably related to the kakapo.

We don’t know a lot about the giant parrot because only two fossils have been found, both of them leg bones and probably from the same individual. They bones are so big that scientists initially thought they belonged to an eagle. Hopefully soon more fossils will come to light so we can learn more about the giant parrot. For all we know, those leg bones belonged to a young parrot that wasn’t fully grown yet. Maybe the adults were even bigger than we think!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!