Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:12 — 13.6MB)

Thanks to Aila, Stella, George, Richard from NC, Emilia, Emerson, and Audie for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

How removing a dam could save North Carolina’s ‘lasagna lizard’

Why Has This North Carolina Town Embraced a Strange Salamander?

Scentists search for DNA of an endangered salamander in Mexico City’s canals

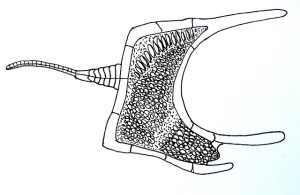

An X-ray of the slender snipe eel:

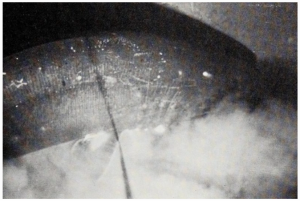

The head and body of a slender snipe eel. The rest is tail [picture by opencage さん http://ww.opencage.info/pics/ – http://ww.opencage.info/pics/large_17632.asp, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26595467]:

_Nemichthys_scolopaceus_2-300x300.jpg)

The hellbender:

A wild axolotl with its natural coloration:

A captive bred axolotl exhibiting leucism:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to talk about some amphibians and fish. Thanks to Aila, Stella, George, Richard from NC, Emilia, Emerson, and Audie for their suggestions!

We’ll start with Audie’s suggestion, the sandbar shark. It’s an endangered shark that lives in shallow coastal water in the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Oceans. A big female can grow over 8 feet long, or 2.5 meters, while males are smaller on average. It can be brown or gray in color, and its dorsal fin is especially big for a shark its size.

The sandbar shark eats fish, crustaceans like crabs, cephalopods like octopuses, and other small animals. It spends a lot of time near the bottom of the seabed, looking for food, and it will also swim into the mouths of rivers. Since it resembles a bull shark, which can live just fine in rivers for quite a while and which can be dangerous to swimmers, people are sometimes afraid of the sandbar shark, but it hardly ever bites people. It just wants to be left alone to find little fish to eat.

Emilia and Emerson both asked to learn more about eels. Eels are fish, but not every animal that’s called an eel is actually an eel. Some are just eel-shaped, meaning they’re long and slender. Electric eels aren’t actually eels, for instance, but are more closely related to catfish.

The longest eel ever reliably measured was a slender giant moray. That was in 1927 in Queensland, Australia. The eel measured just shy of 13 feet long, or 3.94 meters. We talked about some giant eels in episode 401, but this week let’s talk about a much smaller eel, one that Emerson suggested.

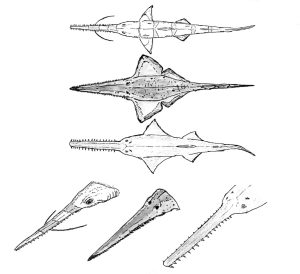

That’s the snipe eel, the name for a family of eels consisting of nine species known so far. They live in every ocean in the world, and some species are deep-sea animals but most live a little nearer the surface. The largest species can grow an estimated 5 feet long, or 1.5 meters, but because all species of snipe eel are so incredibly thin, even the longest individual weighs less than a football, either American or regular, take your pick.

The snipe eel gets its name from its mouth, which is long and slightly resembles the beak of a bird called the snipe. The snipe is a wading bird that pokes its long, flexible bill into mud to find small animals like insect larvae, worms, and snails. But unlike the bird’s bill, the snipe eel’s jaws have a bend at the tip. The upper jaw bends upward, the lower jaw bends downward so that the tip of the jaws are separated. It doesn’t look like that would be very helpful for catching food, but scientists think it helps because the fish’s mouth is basically always open. Since it mainly eats tiny crustaceans floating in the water, it doesn’t even need to open its mouth to catch food. It has tiny teeth along the jaws that point backwards, so when a crustacean gets caught on the teeth, it can’t escape.

The slender snipe eel is especially unusual because it can have as many as 750 vertebrae in its backbone. That’s more than any other animal known. Most of its length is basically just an incredibly long, thin tail, with its organs bunched up right behind its head. Even its anus is basically on its throat.

We don’t know a whole lot about the snipe eel, since it lives deep enough that it’s hardly ever seen by humans. Most of the specimens discovered have been found in the stomachs of larger fish.

Now, let’s leave the world of fish behind and look at some amphibians. First, George wanted to learn about the hellbender, and points out that it’s also called the snot otter or lasagna lizard. I don’t understand the lasagna part but it’s funny.

The hellbender is a giant salamander that lives in parts of the eastern United States, especially in the Appalachian Mountains and the Ozarks. It can grow nearly 30 inches long, or 74 cm, and is the fifth heaviest amphibian alive today in the whole world. It spends almost all its life in shallow, fast-moving streams hiding among rocks. As water rushes over and around rocks, it absorbs more oxygen, which is good for the hellbender because as an adult it breathes through its skin. To increase its surface area and help it absorb that much more oxygen, its skin is loose and has folds along the sides.

The hellbender is flattened in shape and is brown with black speckles on its back. It mostly eats crayfish, but it will also eat frogs and other small animals. Its skin contains light-sensitive cells, which means that it can actually sense how much light is shining on its body even if its head is hidden under a rock, so it can hide better.

Aila and Stella suggested we talk about the axolotl, and a few years ago Richard from NC sent me a lot of really good information about this friendly-looking amphibian. I’d been planning to do a deep dive about the axolotl, which we haven’t talked about since episode 275, but sometimes having a lot of information leads to overload and I never did get around to sorting through everything Richard sent me.

Richard also suggested we talk about a rare mudpuppy, so let’s learn about it before we get to the axolotl. It’s called the Neuse river waterdog, although Richard refers to it as the North Carolina axolotl because it resembles the axolotl in some ways, although the two species aren’t very closely related.

The mudpuppy, also called the waterdog, looks a lot like a juvenile hellbender but isn’t as big, with the largest measured adult growing just over 17 inches long, or almost 44 cm. It lives in lakes, ponds, and streams and retains its gills throughout its life.

The mudpuppy is gray, black, or reddish-brown. It has a lot of tiny teeth where you’d expect to find teeth, and more teeth on the roof of its mouth where you would not typically expect to find teeth. It needs all these teeth because it eats slippery food like small fish, worms, and frogs, along with insects and other small animals.

The Neuse River waterdog lives in two watersheds in North Carolina, and nowhere else in the world. It will build a little nest under a rock by using its nose like a shovel, pushing at the sand, gravel, and mud until it has a safe place to rest. If another waterdog approaches its nest, the owner will attack and bite it to drive it away.

The mudpuppy exhibits neoteny, a trait it shares with the axolotl. In most salamanders, the egg hatches into a larval salamander that lives in water, which means it has external gills so it can breathe underwater. It grows and ultimately metamorphoses into a juvenile salamander that spends most of its time on land, so it loses its external gills in the metamorphosis. Eventually it takes on its adult coloration and pattern. But neither the mudpuppy nor the axolotl metamorphose. Even when it matures, the adult still looks kind of like a big larva, complete with external gills, and it lives underwater its whole life.

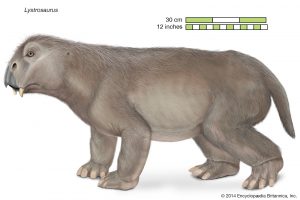

The axolotl originally lived in wetlands and lakes in the Mexico Central Valley. This is where Mexico City is and it’s been a hub of civilization for thousands of years. A million people lived there in 1521 when the Spanish invaded and destroyed the Aztec Empire with introduced diseases and war. The axolotl was an important food of the Aztecs and the civilizations that preceded them, and if you’ve only ever seen pictures of axolotls you may wonder why. Salamanders are usually small, but a full-grown axolotl can grow up to 18 inches long, or 45 cm, although most are about half that length.

Most wild axolotls are brown, greenish-brown, or gray, often with lighter speckles. They can even change color somewhat to blend in with their surroundings better. Captive-bred axolotls are usually white or pink, or sometimes other colors or patterns. That’s because they’re bred for the pet trade and for medical research, because not only are they cute and relatively easy to keep in captivity, they have some amazing abilities. Their ability to regenerate lost and injured body parts is remarkable even for amphibians. Researchers study axolotls to learn more about how regeneration works, how genetics of coloration work, and much more. They’re so common in laboratory studies that you’d think there’s no way they could be endangered—but they are.

A lot of the wetlands where the axolotl used to live have been destroyed as Mexico City grows. One of the lakes where it lived has been completely filled in. Its remaining habitat is polluted and contains a lot of introduced species, like carp, that eat young axolotls as well as the same foods that axolotls eat. Conservationists have been working hard to improve the water quality in some areas by filtering out pollutants, and putting up special barriers that keep introduced fish species out.

Even if the axolotl’s habitat was pristine, though, it wouldn’t be easy to repopulate the area right away. Axolotls bred for the pet trade and research aren’t genetically suited for life in the wild anymore, since they’re all descended from a small number of individuals caught in 1864, so they’re all pretty inbred by now.

Mexican scientists and conservationists are working with universities and zoos around the world to develop a breeding program for wild-caught axolotls. So far, the offspring of wild-caught axolotls that are raised in as natural a captive environment as possible have done well when introduced into the wild. The hard part is finding wild axolotls, because they’re so rare and so hard to spot.

Scientists have started testing water for traces of axolotl DNA to help them determine if there are any to find in a particular area. If so, they send volunteers into the water with nets and a lot of patience to find them.

The axolotl reproduces quickly and does well in captivity. Hopefully its habitat can be cleaned up soon, which isn’t just good for the axolotl, it’s good for the people of Mexico City too.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, corrections, or suggestions, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com.

Thanks for listening!