Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:03 — 26.0MB)

So many interesting hoofed animals in this episode, so many awesome suggestions! Thanks to Page, Elaine, Pranav, Richard E., Richard from NC, and Llewelly!

Further Reading:

Meet the Takin: The Largest Mammal You’ve Never Heard Of

New hope for the elusive okapi, the Congo’s mini giraffe

The Resurrection of the Arabian Oryx

Eucladoceros was not messing around with those antlers:

Megaloceros and Thranduil’s elk in the Hobbit movies. COINCIDENCE?

The stag-moose. What can I say? This thing is AWESOME:

Hoplitomeryx. Can you have too many horns? No, no you cannot:

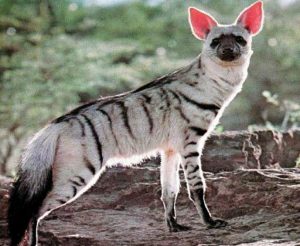

The gerenuk, still beautiful but freaky-looking:

The golden takin looking beautiful [pic from the article linked above]:

The elusive okapi:

Okapi bums [pic from the article linked above]:

The giraffe being really tall and a baby giraffe being somewhat less tall:

A giraffe exhibiting dwarfism but honestly, he is still plenty tall:

The Arabian oryx is just extra:

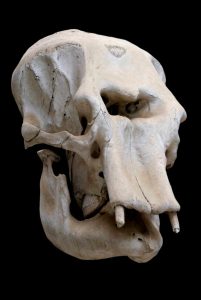

The weird, weird tusks of the babirusa. Look closely:

Show Transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Back in episode 116, we talked about some amazing hoofed animals. This week we’re going to look at some more amazing hoofed animals that you may have never heard about. Some are extinct but some are running around out there looking awesome even as we speak! Thanks to Page, Elaine, Pranav, Richard E., Richard from NC, and Llewelly for their suggestions! If you’re a Patreon subscriber you may recognize part of the end of the episode as largely from a Patreon episode, by the way.

Let’s start with an extinct deer with amazing antlers. Llewelly suggested it, or more accurately replied to a Twitter conversation mentioning it. That counts as a suggestion. It’s been a while but I think the conversation was about the Hobbit movies.

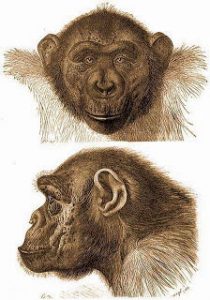

Eucladoceros was a deer the size of a moose but with much weirder antlers. We’re not talking about the Megaloceros, often called the Irish elk, although it was distantly related. Eucladoceros’s antlers were much different. They branched up and out but were spiky like an ordinary deer’s antlers instead of palmate like a moose’s or Megaloceros’s antlers. But they were seriously big, with up to twelve points each and over five and a half feet across, or 1.7 meters. The deer itself stood just under 6 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.8 meters. It’s often called the bush-antlered deer because the antler’s many points look like the branches of a bush.

Eucladoceros lived in Eurasia but we’re not completely sure when it went extinct or why. We don’t really know that much about it at all, in fact, which is surprising because it was such a big animal. It was one of the earliest deer with branching antlers and it probably went extinct before humans encountered it, but we don’t know that for sure either.

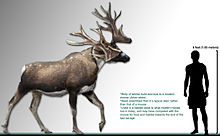

Another deer relation is a gigantic animal called the stag moose that lived at the very end of the Pleistocene, or ice age, until around 13,000 years ago. It probably looked a lot like a huge, muscular deer more than a moose, but had moose-like antlers that grew up to 6 1/2 feet across, or 2 meters. The animal itself stood almost six feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.8 m, which is about the size of the modern moose. It lived in northern North America until melting glaciers allowed other animals to migrate into the area, and the modern moose outcompeted its cousin.

Early deer and deer relations looked a lot different from the deer we’re familiar with today. For instance, Hoplitomeryx. It was a ruminant and therefore related to modern deer, but while it probably looked a lot like a deer, it didn’t have antlers. It had horns. Antlers grow every year from the skull and the animal sheds them later, usually after breeding season. Horns are permanent, usually made of a bony core with a keratin sheath over it.

Hoplitomeryx lived around 11 to 5 million years ago in one small area of Europe. Specifically, it lived on a large island near what is now Italy, although the island is now part of a little peninsula. It probably also lived on other, smaller islands nearby. While some specimens found are quite small, probably due to island dwarfism, some grew as big as the bush-antlered deer, over 5 ½ feet tall, or 1.7 meters.

It had a pair of horns that were shaped like a modern goat’s, that grew from the top of its head and curved backwards. And it had a smaller pair of horns underneath those horns that grew outward. And it had a single horn that was about the same size or bigger and shaped the same as the goat-like horns, but which grew in the middle of the forehead like a really weird unicorn. Also, it had fangs. I am not making this up. It’s sometimes called the five-horned deer for obvious reasons.

We also don’t know much about Hoplitomeryx except that it was really awesome, so let’s move on to our next strange hoofed animal. This one is a suggestion by Page, who wanted to know more about the gerenuk. We talked about it in episode 167 but it’s such an interesting animal that there’s more to learn about it.

The gerenuk is an antelope that lives in East Africa. It’s considered a type of gazelle, although it’s not very closely related to other gazelles. It’s slender with long legs and a long neck, and stands about three feet tall at the shoulder, or 105 cm. The male has a pair of S-shaped, ridged black horns that can grow up to 18 inches long, or 45 cm, while the female doesn’t have horns at all. It’s reddish-brown with a pale belly and a pale stripe down its sides, a short tail, and a white patch around each eye. But as we talked about in episode 167, its legs are extremely thin—so thin that they look like sticks, especially the front legs.

The gerenuk is the only type of antelope that can stand on its hind legs, which it does all the time. It will even use its front legs to pull branches down closer to its mouth while standing on its hind legs. As a result, even though it’s not very big, it can reach leaves that other antelopes can’t. Not only does this mean it can find food where other antelopes can’t, it also means it doesn’t need very much water because it can reach tender leaves with a higher moisture content.

Like many gazelles, the gerenuk marks its territory with scent glands. It has scent glands on its knees, covered with tufts of hair, and scent glands in front of its eyes. So if you see a gerenuk rubbing its knees or face on a branch, that’s why.

Our next hoofed animal is the golden takin, which looks kind of like a musk ox except that it has pale golden fur. But it isn’t a musk ox although it is in the family Bovidae. It’s actually most closely related to sheep but is sometimes referred to as a goat-antelope. It does resemble the mountain goat in some respects, which makes sense because it lives in the Himalayan Mountains in China. As a result, it has a lot of adaptations to intense cold.

It has a thick coat that grows even thicker in winter, with a soft, dense undercoat to trap heat next to the body. It also has large sinus cavities that warm the air it breathes before it reaches the lungs, which means it has a big snoot. Its skin is oily, which acts as a water repellent during rain and snowstorms. In spring it migrates to high elevations, but when winter starts it migrates back down to lower elevations where it’s not quite as cold.

Like the gerenuk, the golden takin will stand on its hind legs to reach leaves, but it has to balance its front legs against something to stay upright. It will eat just about any plant material it can reach, including tree bark, tough evergreen leaves, and bamboo. Yes, bamboo. It sometimes shares the same bamboo forests where pandas live. The golden takin is a strong animal that will sometimes push over small trees so it can eat the leaves. It visits salt licks regularly, and some researchers think it needs the minerals available at salt licks to help neutralize the toxins found in many plants it eats.

Both male and female golden takins have horns, which grow sideways and back from the forehead in a crescent and can be almost three feet long, or 90 cm. It has a compact, muscular build and can stand over four feet tall at its humped shoulder, or around 1.4 m. Baby golden takins are born with dark gold-brown fur that helps camouflage it, but as it ages, it fur grows more and more pale gold. A full-grown golden takin is big enough and strong enough that it doesn’t have many predators. If a bear or wolf threatens it, it can run fast if it needs to or hide in dense underbrush.

Next, let’s learn about an animal requested by both Elaine and Pranav. In the 19th century and earlier, Europeans exploring central Africa kept hearing about an elusive animal that lived deep in the remote forests. It was supposed to be a kind of donkey or zebra, but it was so little-known that some Europeans started calling it the African unicorn because they didn’t even think it existed.

In 1899, a British man named Harry Johnston decided to get to the bottom of the African unicorn mystery. When he asked the Pygmy people about it, they knew exactly what he was talking about and showed him some hoof prints. Like most Europeans at the time, Johnston thought the African unicorn was a zebra, so he was surprised to learn that it had cloven hooves.

The Pygmy people also gave Johnston some strips of skin from the animal, and later he bought two skulls and a complete skin. He sent these to England where the animal was identified as a giraffe relation. It was named Okapia johnstoni, and is known by the name okapi.

The okapi’s discovery by science was as astounding in its way as the coelacanth’s discovery a few decades later. Until it was described in 1901, scientists thought all the giraffe relations had died out long ago. Paleontologists had found fossils that showed how the giraffe evolved from a more antelope-like animal, and suddenly there was a living animal with those same features. It was mind-blowing!

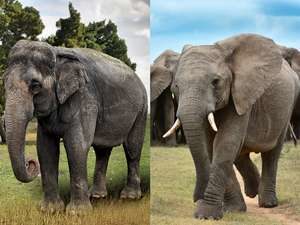

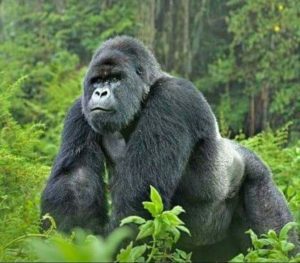

The okapi is the giraffe’s closest living relation, but it doesn’t look much like a giraffe. For one thing, it’s not quite five feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.5 meters, and while it does have a long neck, it’s nothing like as long as a giraffe’s. It looks more like an antelope than a giraffe, at least at first glance. It’s dark reddish-brown with pale gray markings on its face, and its lower legs are white and its rump and upper legs are striped black and white. It also has a tail with a tuft at the end like a giraffe’s. Females are usually larger than males.

The male okapi has a pair of ossicones on his head, but they’re not very long compared to giraffe ossicones. As you may remember, an ossicone is a bony projection from the skull that’s covered with skin and hair. The female has little forehead bumps instead of actual ossicones.

The okapi lives in rainforests in central Africa and is a solitary animal. It has a long tongue like a giraffe which it uses to grab leaves. Its tongue is almost as long as the giraffe’s, up to 18 inches long, or 46 cm, whereas the giraffe’s tongue is 20 inches long, or 56 cm. A female okapi has one calf every two years or so, and in the first month of life, the calf doesn’t defecate at all. Not a single baby okapi poop. Some babies may hold it until they’re ten weeks old. Scientists aren’t sure if this same behavior is found in the wild, since okapis are hard to observe in the wild and most behavioral observations come from captive animals, but the hypothesis is that by not defecating, the baby is less likely to attract the attention of leopards who would smell the poops.

For a long time scientists thought the okapi didn’t make any sounds at all, just some whistles and chuffing sounds. It turns out, though, that a mother okapi communicates with her baby with infrasound, which is below the range of human hearing.

Speaking of giraffes, in March of 2021 a study of the giraffe genome was published, focusing on the giraffe’s adaptations for growing so extremely tall. One interesting discovery is that the giraffe has very little sense of smell although it has excellent eyesight. This makes sense considering that the giraffe’s head is so far above the ground. Most scents left by predators will be on or close to the ground, not high up in the air. The giraffe also doesn’t sleep very much and it shows a lot of genetic adaptations for extremely high blood pressure. It needs that high blood pressure to push blood up its long neck to its brain. Researchers are especially interested in the genetics of blood pressure, since high blood pressure in humans is a serious problem that can lead to all sorts of medical issues.

We’ve talked about giraffes before, especially in episode 50, about the tallest animals. Giraffes have extremely long necks and legs and a big male can stand 19.3 feet high, or 5.88 m, measured at the top of his head. Even a short giraffe is over 14 feet tall, or 4.3 meters. To put that into perspective, the average height of a ceiling in an average home is 8 or 9 feet high, or just over 2.5 meters. This means a giraffe could look into an upstairs window to see if you have any giraffe treats, and not only would it not need to stretch to see in, it would probably need to lower its head.

But in 2015, a team of biologists surveying the animals in the Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda, which is in eastern Africa, noticed a male giraffe that had much shorter legs than usual. They nicknamed him Gimli after one of the dwarf characters from Lord of the Rings, and estimated his height as just over nine feet tall, or about 2.8 meters. Gimli would not be able to peek into an upstairs window, but he was still a fully grown giraffe.

Since dwarfism affects the length of an animal’s limbs, it was obvious that Gimli was actually a dwarf giraffe, the first ever documented.

Then, in 2018, a different team of scientists found a different giraffe in a different place, Namibia in southwest Africa, who was fully grown but also had short legs. He was also a male, nicknamed Nigel, and was hanging around with some other giraffes on a private farm. The farmer had seen Nigel plenty of times over several years. Nigel’s height was estimated at 8 ½ feet tall, or 2.6 meters.

In animals, dwarfism can result from inbreeding, which is sometimes done on purpose by humans trying to breed cute pets. It also just sometimes happens, a random mutation that affects growth hormones. In the wild, an animal with unusually short legs usually doesn’t live very long. Either it can’t run fast enough to escape a predator or it can’t run fast enough to catch prey. Both Gimli and Nigel appear healthy, though, and even a short giraffe is still a large animal that can kick and run pretty fast.

Next, Richard from North Carolina suggested the Arabian oryx, and it is a beautiful and amazing hoofed animal. It’s a large antelope and used to live throughout the Middle East, but by the 1930s, habitat loss and hunting had restricted it to the desert in northwestern Saudi Arabia. Then oil company employees and Arabian princes both discovered the fun that is to be had when you have a car and a machine gun and can just drive around shooting everything you see. Such fun, driving animals to extinction, I’m being sarcastic of course. The last few Arabian oryx survived to 1972, but they were effectively extinct decades before then.

But. Zoos to the rescue. The Arabian oryx is a beautiful animal that does well in captivity, so lots of zoos had them on display. In 1960 conservationists realized they had to act fast if the oryx wasn’t going to go extinct completely, and they started a captive-breeding project called Operation Oryx at the Phoenix Zoo in Arizona, which is in the southwestern United States. They managed to capture three of the remaining wild animals and added to the herd with captive-bred oryxes donated by other zoos.

Operation Oryx was such a success that in only twenty years they were able to reintroduce oryx into the wild. Currently there are an estimated 1,200 oryxes in the wild with another 7,000 or so in zoos and conservation centers around the world. It’s still vulnerable, but it’s not extinct.

The oryx is white with dark brown or black markings, including dark legs and a pair of long, straight, slender black horns. Both males and females have these horns, which can grow up to two and a half feet long, or 75 cm. Since the oryx itself only stands a little over three feet high at the shoulder, or 1 meter, the horns are sometimes longer than the animal is tall. The oryx lives in small herds of mixed males and females, which travel widely in their desert habitat to find food and water. During the hot part of the day, the oryx digs a shallow nest under a tree or bush to lie in. It also has a short tufted tail. I just noticed the tail in a picture I’m looking at. It’s so cute.

In the last weird hoofed animals episode, we ended with a pig relation, so we’re going to end this episode with a pig relation too. Richard E. suggested the babirusa, and you definitely need to know about this weird piggy.

The babirusa is native to four islands in Indonesia. It’s related to pigs, but researchers think it split off from other pigs early on because of how different it is. Females have only one pair of teats, for instance, and usually only one piglet is born at a time, sometimes two. Females make a nest of branches to give birth in.

The babirusa also lacks the little bone in the snout that helps most pig species root. The babirusa only roots in very soft mud, but sometimes it digs for roots with its hooves. It eats plants of all kinds, including cracking nuts with its strong jaws, and will eat insect larvae, fruit, mushrooms, and even occasionally fish and small animals when it can catch them. Unlike most pigs, the babirusa is good at standing on its hind legs to reach branches, much like deer, which is why it’s sometimes called the deer-pig. Its stomach is more like a sheep’s than a pig’s, with two sacs that help it digest fibrous plant material, and it has relatively long, slender legs compared to most pigs.

Most pigs have tusks of some kind, but the babirusa’s are really weird. At first glance they’re just surprisingly long tusks that curve up and back, but when you look closer, you see that the upper pair actually grows up through the top of the snout.

The babirusa boar has two pairs of tusks, which are overgrown canine teeth. The lower pair jut out from the mouth the way most pig tusks do. The upper pair are the weird ones. Before a male babirusa is born, the tooth sockets for its upper canines are normal, but gradually they twist around and the teeth grow upward instead of down. They grow right up through the snout, piercing the skin, and then continue to grow up to 17 inches long, or 43 cm, curving backwards toward the head. In at least one case, a tusk has grown so long it’s actually pierced the boar’s skull.

For a long time researchers assumed males used their tusks to fight, but males fight by rearing on their hind legs and kicking each other with their forehooves. Then researchers decided the tusks were actually for defense during fights, to keep a boar from getting its face kicked. But the tusks aren’t actually very strong and don’t appear to be used for much of anything. Most likely, it’s just a display for females.

The babirusa does well in captivity, even becoming quite tame. Many zoos keep them, which is a good thing because they’re becoming more and more endangered as their island habitats are taken over by farming and development.

So that’s it for the second episode about strange hoofed animals. I guarantee you that we’re going to have a third because there are so many.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!