Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:43 — 20.3MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Thanks to Riley, Richard, and Aiden and Aiden’s unnamed friend for suggestions this week! We’re going to learn about some geckos and other reptiles that live in trees. Thanks also to Llewelly for a small correction about lions. Also, I mispronounced Strophurus–it should be more like Stroff-YOUR-us but I’m too lazy to fix it.

Further reading:

Cancer Clues Found in Gene behind ‘Lemon Frost’ Gecko Color

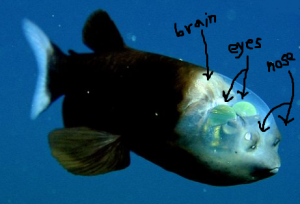

A chameleon’s feets:

A rare healthy lemon frost domestic leopard gecko (photo taken from article linked above):

An ordinary leopard gecko:

I don’t remember what kind of gecko this is (golden spiny-tailed?) but I love it:

A crested gecko looking surprised:

The green iguana:

A black mamba. Watch out!

Flying snake alert!

The draco lizard with its “wings” extended (male) and the draco lizard with its “wings” folded (female):

A parachute gecko showing how it works:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some reptiles, specifically reptiles that live in trees. This is a suggestion from Riley, who wanted to hear about arboreal reptiles in general and the crested gecko in particular. Thanks also to my brother Richard, who suggested the dragon-tailed gecko. An anonymous reviewer also suggested the leopard gecko so we’ll learn about that one too. Specifically, the anonymous reviewer said “me and my friend Aiden suggest either red foxes or leopard geckos.” We actually covered the red fox in episode 138, about city animals, and in episode 106, about domestication, but we’ve only mentioned the leopard gecko briefly way back in episode 20.

Arboreal animals have some traits in common, whether they’re reptiles or mammals or something else. In general, an animal that spends most of its time in trees is small and lightweight, either has long legs or very short legs, may have a long tail to help it balance, and may also have various adaptations to its feet to help it maneuver through branches.

This is the case with the chameleon, which is arboreal and has weird feet. Its feet look more like mittens. The feet are called zygodactylous, which means it has two toes pointing forward and two pointing backwards. A lot of birds have feet like this too. Chameleons have other adaptations for arboreal life, like prehensile tails that can twine around a twig to help it keep its balance. The chameleon really deserves its own episode some day, so let’s move on to learn about some geckos.

The biggest gecko known grows up to two feet long, or 60 cm, but most are much smaller. There are more than 1,800 species known and they’re all really interesting and honestly, adorable. They’re mostly nocturnal and eat small animals like insects. About 60% of all gecko species have toe pads that allow them to walk up walls and windows and even across ceilings.

Like many other lizards, most geckos species can drop their tail if a predator attacks. The tail thrashes around on its own for several minutes, distracting the predator so the gecko can escape. The gecko later regrows a little stumpy tail, but it can’t drop it a second time. Many species of gecko store fat in the tail, so it needs that tail. A genus of gecko called the fish-scaled gecko, which lives on Madagascar and nearby islands, has big scales that come loose easily if an animal tries to bite it or if a scientist tries to capture it. The predator gets a mouthful of scales while the gecko runs off. The scales grow back eventually and can be lost again.

Scientists are always interested in animals that can regenerate parts of the body, to learn how that works. A study published in 2017 identified the type of cells that allow the gecko to regrow the part of its spinal cord that’s lost with its tail. In 2018, the same team published their discovery that geckos renew brain cells. This is amazing, since humans and many other animals are born with all the brain cells they’ll ever have, and if something happens to injure the brain, the damage can’t be repaired. Maybe one day people will be able to heal their brains just like the gecko does.

Most species of gecko don’t have eyelids. Instead, the gecko has a protective scale over its eyeball. To remove dust and other debris from the scale, the gecko licks its eyes.

The leopard gecko grows about 11 inches long, or almost 28 cm, and is one of the species that doesn’t have toe pads. That makes it easier to keep in captivity, since it’s less likely to climb out of its terrarium. It’s a handsome lizard that’s yellowish or orangey in color with black spots, but baby leopard geckos actually have black stripes. It’s native to parts of the Middle East and south Asia where it’s mostly hot and dry, and in the wild it spends its day in a burrow and only comes out at night to hunt.

The leopard gecko has been kept as a pet for so long that some people consider it the first truly domesticated lizard. It’s easy to take care of and is usually comfortable around people. Breeders select for brighter colors than are found in wild geckos, including various color and pattern morphs.

One color variety of domestic leopard gecko is called the lemon frost morph, an especially attractive coloration. It’s a pastel yellow with white underneath and brown or black speckles that form broad bands over the lizard’s back. It’s really pretty and when the trait cropped up unexpectedly around 2015, its owner started breeding for the color. Lemon frost babies were rare and incredibly expensive, with people paying up to $2,000 for a single gecko.

Unfortunately, people soon learned that lemon frost geckos were prone to a type of rare skin cancer that affects the iridophores, which are pigment-producing cells. Up to 80% of all lemon frost morphs develop the cancer. Geneticists have discovered that the color morph is due to a single mutation in a single gene, but that the change in that gene also makes the gecko susceptible to cancer. Scientists are now trying to figure out more about how it works in hopes of learning how to prevent skin cancer in humans.

The dragon-tailed gecko is one name for the golden spiny-tailed gecko, one of twenty species in the genus Strophurus. All Strophurus geckos are from Australia and they all spend most of their lives in trees and shrubs. Unlike other geckos, Strophurus geckos don’t drop their tails when threatened. Instead, they have a unique way of deterring predators. A Strophurus gecko can squirt an incredibly smelly liquid from tiny pores in its tail. If it feels threatened, instead of dropping its tail, it will raise its tail up and wave it back and forth as a warning. It also opens its mouth to reveal a bright yellow or blue lining, which alerts the potential predator that this is not a lizard it wants to mess with. If that doesn’t scare the predator away, it will squirt liquid at its face. The liquid is sticky and smells horrible, and if it gets in an animal’s eyes it can cause eye irritation.

Strophurus geckos grow up to 5 inches long, or 13 cm, and species may look very different from each other. Some are drab and spiny, some are smooth and brighter in color. The dragon-tailed gecko has a broad reddish or golden stripe down the top of its tail.

The crested gecko is native to a collection of remote Pacific islands called New Caledonia. It can grow more than 10 inches long, or 25 cm. It has tiny spines above its eyes that look like eyelashes and more spines in two rows down its back, like a tiny dragon. It can be brown, reddish, orange, yellow, or gray, with various colored spots, which has made it a popular pet. These days all pet crested geckos were bred in captivity, since it’s now protected in the wild.

The crested gecko spends most of its time in trees, and not only does it have adhesive toe pads, it also has tiny claws. Most geckos don’t have claws. It can drop its tail like other geckos, but it doesn’t grow back. This doesn’t seem to bother the gecko, though.

The crested gecko was discovered by science in 1866, but wasn’t seen after that in so long that people thought it was extinct. Then it was rediscovered in 1994, so hurrah for the crested gecko!

Let’s move on from geckos to some other arboreal reptiles. A lot of reptiles live mostly in trees, and not all of them are small. The green iguana, for instance. It’s native to southern Mexico into parts of South America but has been introduced in many other places in the Americas, where it’s often considered an invasive species. In warm weather it lives in trees, although it will climb down to the ground in cool, rainy weather, and it can grow up to six and a half feet long, or 2m.

Although the iguana can be really long, most of its length is tail. It has an incredibly long tail for its size. It’s not that heavy, either, with the biggest green iguana ever weighed only a little more than 20 lbs, or 9.1 kg. Most are much lighter. It has long legs and long toes with claws, which makes it a good climber. It uses its tail to balance. It’s usually a drab olive-green or brown in color, although babies are brighter green with reddish spots and some adults are more orange in color. The tail is patterned with broad stripes. It has spines along its back and down its chin, and males develop a large dewlap that hangs down under the neck.

Although the iguana looks like a small dragon, it eats leaves, flowers, fruit, and other plant material, although it will also sometimes eat a grasshopper or snail and even bird eggs every so often. Many people keep green iguanas as pets, but they can be hard to keep healthy in captivity.

Another big reptile that lives in trees is the black mamba, a snake that lives in parts of Africa. It’s a slender snake that can be black in color, but that’s actually rare. The name black mamba comes from the inside of the snake’s mouth, which is black. When it feels threatened, it will raise its head high and open its mouth as a threat display. It can even flatten its neck to look like a hood like some cobras do. You really don’t want to see this threat display, because the black mamba’s venom is deadly and it’s an aggressive snake. Without treatment and antivenin, someone who is bitten can die within 45 minutes.

The mamba’s body can be gray, gray-green, brown, or brownish-yellow. It can grow nearly 15 feet long, or 4.5 meters, which makes it the second-longest venomous snake in the world, after the king cobra that we talked about in our Q&A episode last week.

The black mamba mostly lives in open forests and savannas, and it’s equally at home on the ground and in trees. It hides in termite mounds or in holes in trees at night, then comes out in the morning to warm up in the sunshine. Then it goes hunting, usually for small animals like rodents but also for larger ones like the rock hyrax. The rock hyrax can grow almost two feet long, or 50 cm, and looks kind of like a big rodent even though it’s not a rodent. It’s actually most closely related to the elephant. The black mamba will sneak up on a hyrax, bite it quickly, and then just wait until it dies to swallow it whole. The mamba also hunts birds and bats, which is why it spends so much time in the trees.

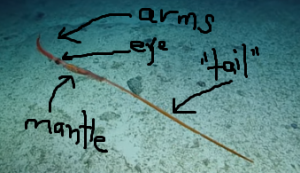

Some reptiles are so well adapted to living in trees that they can glide from tree to tree, like the flying snakes we talked about in episode 56. Flying snakes live in southeast Asia, and of course they can’t really fly. A flying snake has ridged scales on its belly that help it climb trees, and when it wants to move from one tree to another, it can flatten its body by flaring its ribs. This gives it more surface area to catch air, like a long skinny Frisbee. It’s been measured as gliding as far as 100 meters, or 109 yards, which is just a little longer than an American football field.

The largest species of flying snake, the golden tree snake, can grow over four feet long, or 1.3 meters. It’s striped black, gold, and yellow although some may be green and black. It eats small animals it finds in trees, including frogs, birds, bats, and lizards. It’s venomous, but its venom is weak and not dangerous to humans.

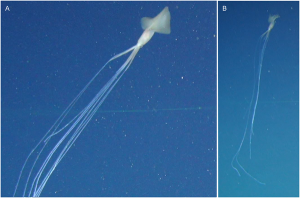

Many lizards can glide too, including the draco lizard. The draco lizard is common throughout much of southeast Asia and spends almost its whole life in trees, eating insects like ants and termites. It’s a small, slender lizard that only grows about 8 inches long at most, or 20 cm, and that includes its very long tail. Many gliding animals, like the flying squirrel, have gliding membranes called patagia that stretch from the front legs to the back legs, but the draco lizard is different. It has greatly elongated ribs that it can extend like wings, and the skin between the ribs acts as a patagium. This skin is usually yellow or brown so that the lizard looks like a falling leaf when it’s gliding.

The male draco also has a brightly colored dewlap under its chin that it can extend to attract a mate. When a female is ready to lay her eggs, she climbs down from her tree, finds some soil that’s soft enough for her to stick her head into to make a little hole, and then lays her eggs in the hole and covers them with dirt to hide them.

The draco lizard is beautiful and looks like a tiny dragon, and I want one to live in my garden and every time I go out to water my plants or pull weeds, I want it to fly down and ride around on my shoulder.

To bring us full circle, some geckos can also glide using thin membranes of skin around their body, legs, tail, and toes that act as patagia. They’re called parachute geckos, which is just perfect.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!