Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:01 — 13.5MB)

Thanks to Nora, Holly, Stephen, and Aila for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

How ‘bin chickens’ learnt to wash poisonous cane toads

Monkeys in Australia? Revisiting a Forgotten Furry Mystery Down Under

The Australian white ibis:

The greater glider looks like a toy:

The thorny devil is very pointy:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to talk about some animals native to Australia, which is Nora’s suggestion. We’ll learn about animals suggested by Holly, Stephen, and Aila, along with a mystery animal reported in the 1930s in northern Australia.

Australia isn’t currently connected to any other landmass and hasn’t been for about 50 million years. That means that most animals on the continent have been evolving separately for a very long time. While in other parts of the world placental mammals took over many ecological niches, marsupials are still the dominant mammal type in Australia. Most marsupial females give birth to tiny, helpless babies that then continue their development outside of her body, usually in a pouch.

But let’s start the episode not with a marsupial but with a bird. Stephen suggested the Australian white ibis, a beautiful bird that doesn’t deserve its nickname of bin chicken.

The white ibis is related to ibises from other parts of the world, but it’s native to Australia, and is especially common in eastern, northern, and southwestern Australia. It’s a large, social bird that likes to gather in flocks. Its body is mostly white with a short tail, long black legs, and a black head. Like other ibises, the adult bird’s head is bare of feathers. It also has a long, down-curved black bill that it uses to dig in the mud for crayfish and other small animals. When the bird spreads its magnificent black-tipped wings, it displays a stripe of featherless skin that’s bright red.

The Australian white ibis prefers marshy areas where it can eat as many frogs, crayfish, mussels, and other animals as it can catch. But at some point around 50 years ago, the birds started moving into more urban areas. They discovered that humans throw out a lot of perfectly good food, and before long they started to become a nuisance to people who had never encountered raccoons and didn’t know they should clamp those trash barrels closed really securely.

But no matter how annoying the Australian white ibis can be to people, it’s been really helpful in another way. In the 1930s, sugarcane plantation owners wanted to control beetles and other pests that eat sugarcane plants, so they released a bunch of cane toads in some of their fields in Queensland. But the cane toads didn’t do any good eating the beetles. Instead, they ate native animals and spread like wildfire. Since the toads are toxic, nothing could stop them, and there are now an estimated two billion cane toads living in Australia. But the Australian white ibis eventually figured out how to deal with cane toads.

The ibis will grab a cane toad, then whip it around and throw it into the air so that the toad secretes its toxins in hopes that the bird will leave it alone. Then the ibis will wash the toad in water or wipe it in wet grass, which washes away the toxins. Then the ibis eats the toad. Goodbye, toad!

Our next Australian animal is one suggested by Holly, the greater glider. When I saw the picture Holly sent, I was convinced it wasn’t a real animal but a toy plushie, but that’s just what the greater glider looks like. It’s incredibly cute!

The greater glider lives in eastern Australia, and as you might guess from its name, it is the largest of the three glider species found in Australia, and it can glide from tree to tree on flaps of skin between its front and back legs. Until 2020 scientists thought there was only one species of glider with local variations in size and coat color, but it turns out those differences are significant enough that it’s been split into three separate but closely related species.

The greater glider is nocturnal and only eats plant material, mostly from eucalyptus trees. It has a long fluffy tail, longer than the rest of its body is. Its tail can be as much as 21 inches long, or 53 cm, while its body and head together can measure as much as 17 inches long, or 43 cm. It has dense, plush fur, a small head with big round ears, black eyes, and a little pinkish nose, and it superficially looks like a big flying squirrel. But the greater glider isn’t a rodent. It’s a marsupial, closely related to the ringtail possum. Some individuals have dark gray or black fur and some have lighter gray or brown fur, but all greater gliders have cream-colored fur on their tummies.

The greater glider’s gliding membranes, also called patagia, are connected at what we can refer to as their elbows and ankles. It uses its long tail as a rudder and it’s very good at gliding from tree to tree. It almost never comes down to the ground if it can avoid it. When it glides, it folds its front legs so its little fists are under its chin and its elbows are stuck out, which stretches the membranes taut.

Aila suggested we learn more about the thorny devil, an Australian reptile we talked about way back in episode 97. It’s a spiky lizard that grows to around 8 inches long, or 20 cm. In warm weather its blotchy brown and yellow coloring is paler than in colder weather, when it turns darker. It can also turn orangey, reddish, or gray to blend in to the background soil. Its color changes slowly over the course of the day as the temperature changes. It also tends to turn darker if something threatens it.

It has a thick spiny tail that it usually holds curved upward, which makes it look kind of like a stick. It moves slowly and jerkily, rocking back and forth on its legs, then surging forward a couple of steps. Researchers think this may confuse predators. It certainly looks confusing.

As if that wasn’t enough, the thorny devil has a false head on the back of its neck. It’s basically a big bump with two spikes sticking out of its sides. When something threatens the lizard, it ducks its head between its forelegs, which makes the bump on its neck look like a little head. But all its spines make it a painful mouthful for a predator. If something does try to swallow it, the thorny devil can puff itself up to make it even harder to swallow, like many toads do. It does this by inflating its chest with air.

The thorny devil eats ants, specifically various species of tiny black ants found only in Australia. It has a sticky tongue to lick them up. This is very similar to the horned lizard of North America, also called the horny toad even though it’s not a toad, which we talked about most recently in episode 376. But despite their similarities in looks, behavior, and diet, the horned lizard and the thorny devil aren’t closely related. It’s just yet another example of convergent evolution.

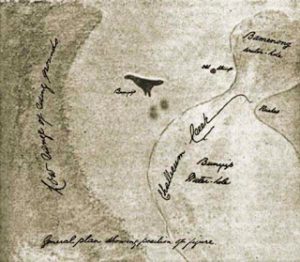

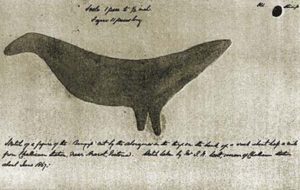

Now, let’s finish with a strange report from the 1930s about a colony of hundreds, if not thousands, of monkeys in Australia. Australia doesn’t have very many native placental mammals, and no monkeys. But several Australian newspapers reported in 1932 that a party of gold prospectors encountered the monkeys in northern Australia, specifically Cape York Peninsula. The monkeys were reportedly gathered in one area to eat a huge crop of red nuts, and they appeared to be large monkeys that weighed up to 30 lbs, or 13 kg. Another gold prospector said in follow-up articles that he too had seen the monkeys and even shot a few of them, although he hadn’t saved any part of the bodies.

Newspaper hoaxes were pretty common back in the day, but by the 1930s things had mostly settled down and papers were more interested in imparting actual news instead of making it up. Cape York Peninsula was quite remote at the time, with rivers, rainforests, and savannas where a lot of animals unknown to science probably still live. But not monkeys!

One thing to remember is that at the end of the 19th century, it was a fad to release animals from one area into another. That’s how the European starling was introduced to North America, where it has become incredibly invasive. In the early 1890s, a group of people released a hundred starlings into New York City’s Central Park, because they wanted all the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s writings to be present in the United States. This fad included Australia, where colonizers tried to release all sorts of animals. Most of the animals didn’t survive long, and we don’t have any records of monkeys being released, but it’s possible that someone just did it for fun and didn’t tell anyone.

Another suggestion is that the prospectors saw tree kangaroos and thought they were monkeys, even though tree kangaroos don’t actually look like monkeys. They look like little kangaroos that live in trees, not to mention they’re mostly nocturnal. Besides, the local Aboriginal people reportedly told the prospectors about the monkeys, and they would have identified tree kangaroos easily if that’s what they were. No other native Australian animal known to live in the area resembles a monkey either.

Zoologist Karl Shuker suggests the monkeys might have been macaques native to New Guinea. New Guinea isn’t all that far away from Australia, and macaques were often kept as pets too. It would have been pretty easy for someone to buy a bunch of macaques, import them on a ship, and release them into the wilderness. Or the macaques might have gotten there on their own, rafting to Australia on fallen trees washed out to sea during storms.

If there really were monkeys in Australia 90 years ago, of course, the big question is: are they still there?

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!