Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:29 — 17.7MB)

Many animals have differences between males and females, but some species have EXTREME differences!

The elephant seal male and female are very different sizes:

The huia female (bottom) had a beak very different from the male (top):

The eclectus parrot male (left) looks totally different from the female (right):

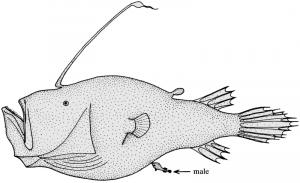

The triplewart seadevil, an anglerfish. On the drawing, you can see the male labeled in very small letters:

The female argonaut, also called the paper nautilus, makes a delicate see-through shell:

The male argonaut has no shell and is much smaller than the female (photo by Ryo Minemizu):

Lamprologus callipterus males are much larger than females:

The female green spoonworm. Male not pictured because he’s only a few millimeters long:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I still have a lot of listener suggestions to get to, and don’t worry, I’ve got them all on the list. But I have other topics I want to cover first, like this week’s subject of extreme sexual dimorphism!

Sexual dimorphism is when the male of a species looks much different from the female. Not all animals show sexual dimorphism and most that do have relatively small differences. A lot of male birds are more brightly colored than females, for instance. The peacock is probably the most spectacular example, with the males having a brightly colored, iridescent fan of a tail to show off for the hens, which are mostly brown and gray, although they do have iridescent green neck feathers too.

But eclectus parrot males and females don’t even look like the same bird. The male is mostly green while the female is mostly red and purple. In fact, the first scientists to see them thought they were different species.

Males of some species are larger than females, while females of some species are larger than males. In the case of the elephant seal, the males are much larger than females. We talked about the northern elephant seal briefly last week, but only how big the male is. A male southern elephant seal can grow up to 20 feet long, or 6 meters, and can weigh up to 8,800 pounds, or 4,000 kg. The female usually only grows to about half that length and weight. The difference in this case is because males are fiercely territorial and fight each other, so a big male has an advantage over other males and reproduces more often. But the female doesn’t fight, so her smaller size means she doesn’t need to eat as much.

Another major size difference happens in spiders, but in this case the female is far larger than the male in many species. For instance, the body of the female western black widow spider, which lives throughout western North America, is about half an inch in length, or 16 mm, although of course that doesn’t count the legs. But the male is only half this length at most. Not only that, the male is skinny where the female has a large rounded abdomen, and the male is brown with pale markings, while the female is glossy black with a red hourglass marking on her abdomen. Female western widows can be dangerous since their venom is strong enough to kill many animals, although usually their bite is only painful and not deadly to humans and other mammals. But while the male does have venom, he can only inject a tiny amount with a bite so isn’t considered very dangerous in comparison.

The reason many male spiders are so much smaller than females is that the females of some species of spider will eat the male after or even during mating if she’s hungry. The smaller the male is, the less of a meal he would be and the less likely the female will bother to eat him. In the case of the western black widow, the male prefers to mate with females who are in good condition. In other words, he doesn’t want to spend time with a hungry female.

If you remember episode 139, about skunks and other stinky animals, we talked about the woodhoopoe and mentioned the bill differences between males and females. The male woodhoopoe has a longer, more curved bill than the female because males and females eat a slightly different diet of insects so they won’t compete for the same food sources.

But a bird called the huia took beak differences to the extreme. The huia lived in New Zealand, although it officially went extinct in 1907. It was a wattlebird, which gets its name from the brightly colored patch of skin on either side of the face, called wattles. In the case of the huia, the wattles were orange, while the feathers over most of the body were glossy black. It also had a strip of white at the tip of the long tail. The male’s beak was fairly long and pointy, although it also curved down slightly. But the female’s beak was much longer and more slender, curving downward in an arc.

The huia lived in forests in New Zealand, where it ate insects, especially beetle grubs that live in rotting logs. People used to think that a mated pair worked together to get at grubs and other insects. The male would use his shorter, stouter bill to break away pieces of rotting wood until the grub’s tunnel was exposed, and then the female would use her longer, more slender bill to fish the grub out of the tunnel. But actual observations of the huia before it went extinct indicate that it actually didn’t do this. Like the woodhoopoe, males and females preyed on different kinds of insects. The male did break open rotting wood with its beak in a way that’s very different from woodpeckers, though. Instead of hammering at the wood, it would wedge its bill into a crevice of the wood and open its beak, and the muscles and other structures it used to do so were so strong that it could easily break pieces of wood off. This action is known as gaping and other birds do it too, but the huia was probably better at it than any other bird known.

The huia went extinct partly due to habitat loss as European settlers cleared forests to make way for farming, and partly due to overhunting. Museums wanted stuffed huias for display, and the feathers were in demand to decorate hats. And as a result, we don’t have any huias left.

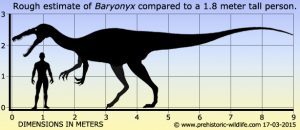

Sometimes the size difference between males and females reaches extreme proportions. We’ve talked about the anglerfish several times in different episodes, and it’s a good example. It’s a deep-sea fish with a bioluminescent lure on its head that it uses to attract prey. Different species grow to different sizes, but let’s just talk about one this time, the triplewart seadevil.

The triplewart seadevil is found throughout much of the world’s oceans, preferably in medium deep water but sometimes in shallow water and sometimes as deep as 13,000 feet, or 4000 meters. The female grows to about a foot long, or 30 cm. It’s black in color, although young fish are brown. Its body is covered with short spines and it has a lure on its head like other anglerfish. The lure is called an illicium, and it’s a highly modified dorsal spine that the fish can move around, including extending and retracting it. At the end of the illicium is a little bulb that contains bioluminescent bacteria. Whatever animals are attracted to the glowing illicium, the fish gulps down with its great big mouth.

But that’s the female triplewart seadevil. The male is tiny, only 30 mm long at the most. The male doesn’t have an illicium; instead, his jaws and teeth are specialized for one thing: to bite onto the female and never let go. When a male finds a female, he chooses a spot on her underside to latch on, and once he does, his mouth and one side of his body actually fuse to the female’s body. Their circulatory and digestive systems fuse too. Before the male finds a female, he has great big eyes, but once he fuses with a female his eyes degenerate because he no longer needs them. He’s fully dependent on the female, and in return she always has a male around to fertilize her eggs. But this attachment is actually pretty rare, because it’s hard for deep-sea fish to find each other.

Another sea creature where the females are much larger and very different from the males is the argonaut, or paper nautilus. The argonaut is an octopus that lives in the open ocean in tropical and subtropical waters. Instead of living on the bottom of the ocean, though, the paper nautilus lives near the surface, and while the female looks superficially similar to a nautilus, it’s only distantly related.

The female argonaut generally grows to about 4 inches long, or 10 cm, although the shell she makes can be up to a foot across, or 30 cm. In contrast, males are barely half an inch long, or 13 mm. The female’s eight arms are long because she uses them to catch prey, with two of her arms being larger than the others. She grabs small animals like sea slugs, crustaceans, and small fish and bites it with her beak, and like other octopuses she can inject venom at that point too. But the male has tiny little short arms except for one, which is slightly larger.

Like other cephalopods, the male uses one of his arms to transfer sperm to the female so she can fertilize her eggs. In most cephalopods that means an actual little packet of sperm that the male places inside the female’s mantle for her to use later. But in the argonaut, the male’s larger modified arm is called a hectocotylus, and it has little grooves that hold sperm. The male inserts the hectocotylus into the female’s mantle, then detaches it and leaves the arm inside her. Then he leaves and regrows the arm, as far as researchers know. We don’t actually know for sure since it’s never been observed, but octopuses do have the ability to regenerate lost arms. The female usually keeps the hectocotylus and sometimes ends up with several.

At that point the female creates a shell by secreting calcite from the tips of her two larger arms. The shell is delicate, papery, and white, and it resembles the shell of the ammonite, which we talked about in episode 86. The female lays her eggs inside the shell, then squeezes inside too, although she can come and go as she likes.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about the argonaut, but we know more than we used to. In the olden days people thought the female used her two larger arms as sails at the surface of the water. Eventually scientists figured out that was wrong, but they were still confused as to why there only seemed to be female argonauts. They didn’t know that the males were so small and so different, and in fact when early researchers found hectocotyluses inside the females, they assumed they were parasitic worms of some kind. Eventually they worked that part out too.

But still, for a very long time researchers thought the argonaut’s shell was just for protecting the eggs, but it turns out that the female uses the shell as a flotation device. She can control how much air the shell contains, which allows her to control how close to the surface she stays. In a 2010 study of argonauts rescued from fishing nets and released into a harbor, if the shell doesn’t contain enough air, the argonaut will jet to the surface and stick the top of its shell above the water. The shell has small openings at this point so air can get in, and once the argonaut decides it’s enough, she seals the holes by covering them with two of her arms. Then she jets downward again until she’s deep enough below the surface that the pressure compresses the air inside the shell and cancels out the weight of the shell. This means the argonaut won’t bob to the surface but she also won’t sink, and instead she can just swim normally by shooting water from her funnel like other octopuses.

A species of cichlid fish from Lake Tanganyika in Africa, Lamprologus callipterus, also differs in size due to a shell, but not like the argonaut. Instead, the male is much larger than the female. The male can be up to five inches long, or nearly 13 cm, while the female is less than two inches long, or 4 ½ cm. The females lay their eggs in shells, but not shells they make. The shells come from snails, so the male needs to be larger so he can pick up and carry a big empty shell. The female, though, still needs to be small enough to fit inside the shell.

A moth called the rusty tussock moth is also sexually dimorphic. Its caterpillar grows around 1 to 1.5 inches long, or 3 to 4 cm, with females being a little larger than male caterpillars but otherwise very similar. But after the caterpillars pupate, they’re much different. The male moth has orangey or reddish-brown wings and a wingspan of about 1.5 inches, or almost 4 cm. The female doesn’t have wings at all. She emerges from her cocoon and perches next to it, and releases pheromones that attract a male. After the female mates, she lays her eggs on her old cocoon and dies, as does the male.

Let’s finish up with an animal you may never have heard of, the green spoonworm. It’s a marine worm that lives throughout much of the Mediterranean and the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. It lives on the sea floor in shallow water, partly buried in gravel and sand. The female grows up to about six inches long, or 15 cm, and sort of looks like a mostly deflated dark green balloon, although it may also look kind of lumpy. It also has a feeding proboscis that it can extend several feet, or about a meter.

As a larva, the green spoonworm floats around in the water, but whether it becomes male or female depends on where it settles. If it lands on the seafloor it transforms into a female and starts secreting a toxin called bonellin. Bonellin is what gives the green spoonworm its dark green color. The bonellin is mostly concentrated in the feeding proboscis and allows the spoonworm to paralyze and kill the tiny animals it eats.

But if the larva happens to land on a female green spoonworm, contact with the bonellin causes it to become a male. And the male is only a few mm long, doesn’t produce bonellin, and can’t even survive on its own. The female sucks the male into her body through the feeding proboscis, but instead of digesting him, he lives inside her and fertilizes her eggs. In return she provides him with all the nutrients he needs. A female may have more than one male living inside her, making sure that her eggs will always be fertilized.

There are lots more animals that show extreme sexual dimorphism, of course, but that at least gives you an idea of how different animals evolve to fit different environmental pressures. Weird as they seem to us, to the animals in question, it’s just normal–and it’s our appearance and how we do things that would seem weird to them. Perspective is everything.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!