Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:37 — 17.9MB)

This week we’re going to learn about some more big cats, especially the mysterious onza of Mexico and the yemish of Patagonia.

And you should totally check out the charming podcast Cool Facts about Animals.

A jaguar:

A jaguarundi:

A puma, not dead:

The Rodriguez onza, dead:

A giant otter:

Further reading:

The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals by Karl P.N. Shuker

Monsters of Patagonia by Austin Whittall

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about a couple of mystery cats that you might not have heard of, and learn about a few non-mystery animals along the way.

There are several cats native to Mexico. We’ve talked about the puma recently, in episode 52. It’s the same cat that’s also called the cougar or mountain lion, and it lives throughout most of the Americas. It’s tawny or brownish in color with few markings beyond dark and white areas on the face, and sometimes faint tail rings and mottled spots on the legs.

The jaguar is a spotted cat related to lions, tigers, leopards, and other big cats. It lives throughout much of Central and South America, and in North America as far north as Mexico, and was once common in the southwestern United States too but was hunted to extinction there. It prefers tropical forests and swamps, likes to swim, and is relatively stocky with a shorter tail than its relatives. Its background color is tawny or brownish with a white belly, and its spots, called rosettes, are darker. But melanistic jaguars aren’t especially uncommon. They look all black at first glance, but their spots are visible up close. Oh, and a big shout-out to the charming podcast Cool Facts About Animals who did a show about jaguars recently. I definitely recommend it, especially if you’ve got younger kids who love animals.

In 2011, a hunter and his daughter in Arizona took pictures of a spotted cat treed by their dogs, and alerted wildlife officials. The officials studied the photos and said yes, that’s a jaguar. Since then, he’s been monitored by trail cam and conservationists working in the Santa Rita Mountains. Since jaguars have unique spot patterns, we know it’s the same cat, a male that local elementary school kids have named El Jefe. Officials think El Jefe moved to Arizona from a nearby jaguar sanctuary in Mexico, and for years he was the only known jaguar in the United States. In late 2017, a second male jaguar was caught on camera in southern Arizona. Researchers hope that more jaguars will move into the area, which was part of their original range.

Pumas and jaguars are the two biggest cats found in Mexico. But there is a third big cat, a mystery big cat. The onza has been reported in Mexico for centuries. It’s supposed to look like a puma but more lightly built with longer legs and possibly darker fur or dark markings, especially striping on the legs.

The first problem is the name onza. The term is applied to a lot of different big cats in Mexico and other Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries. For instance, in Brazil the word onça means jaguar, and in fact the jaguar’s scientific name is Pathera onca. The related English word ounce was once the name of the lynx and is now sometimes used for the snow leopard, Panthera uncia. So it’s possible that old reports of onzas just refer to pumas or jaguars, or one of the many other cats that live in the area, such as the jaguarundi.

The jaguarundi sometimes lives in Mexico as far north as southern Texas, although it’s much more common in South and Central America. It’s black or brownish-grey, which is called the grey phase, or red-brown or tawny, called the red phase. In the past the two phases were thought to be separate species. Adult jaguarundis don’t usually have any markings, but cubs have spots on their bellies. That is adorable. It’s closely related to the puma but is smaller, not much bigger than a domestic cat, and unlike most cats it’s diurnal instead of nocturnal, which means it’s mostly active during the day.

The jaguarundi has a flattish head, more like an otter than a cat. A gray phase jaguarundi may be the animal referred to in the writings of Bernal Diaz del Castillo, who in the early 16th century wrote about a lion that resembled a wolf in Montezuma’s menagerie, in 1519. It also happens to be called an onza in some parts of Mexico.

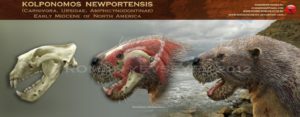

Some animals labeled onzas have been killed and examined. On January 1, 1986 a big cat killed in Sinaloa State in Mexico, called the Rodriguez onza, was examined by a team of experts, including Stephen O’Brien, an expert in feline molecular genetics. They reported that the animal’s DNA was indistinguishable from that of a puma. But it definitely didn’t look like an ordinary puma. I have a picture of it in the show notes. It was long-bodied and slender with dark markings. So it’s possible that stories of onzas arose from sightings of pumas with this sort of coat color variation, or it’s possible there is a remote population of pumas with a leggier build than ordinary pumas, and every so often one wanders out where it’s seen or killed. Pumas can show considerable variance in appearance, so it wouldn’t be that unusual for an occasional individual to be born that’s longer legged than most and that also has more or darker markings than usual.

Then again, who knows? There might be a subspecies of puma or a completely different species of cat out there. If so, hopefully we’ll find out more about it soon so it can be protected and studied.

Jaguarundis make a lot of different vocalizations. Here’s one. It sounds more like a bird than a cat, but I promise you, that’s a jaguarundi.

[cat sound]

Way back in episode 22 I touched on the yemish, or Patagonian water tiger. I think it’s time to revisit it in more detail. Look, I have a fantastic book called Monsters of Patagonia so you’re going to be hearing about Patagonia on this podcast for a long, long time.

The iemisch, or hyminche, or lemisch, or some other variation, is often called a water tiger but linked not with a feline at all, but with a ground sloth. This is entirely the fault of a single man, Florentino Ameghino.

Ameghino lived in the late 19th century and died in 1911. He was from Argentina, born to Italian immigrants, and is still highly regarded as a paleontologist, anthropologist, zoologist, and naturalist, from back in the days when you could specialize in lots of disciplines and still do tons of field work. He has an actual crater on the moon named after him. You don’t get a moon crater unless you’re pretty awesome. But Ameghino had at least one bee in his bonnet, and it involved giant ground sloths like megatherium. He was convinced they were still alive in the remote areas of South America, especially Patagonia.

In an 1898 paper he wrote about the yemish in Patagonia, which he said was a “Mysterious four legged massive beast, of a terrible and invulnerable appearance, whose body cannot be penetrated by missiles or burning branches. They call it Iemisch or ‘water tiger’ and mentioning its name terrorizes them; when interrogated and asked for details, they become grim, drop their heads, turn mute or evade answering.”

I got this quote from the Monsters of Patagonia book, of course. You can find a link in the show notes if you want to order your own copy of the book. It’s a fun read, but I should point out that I do a lot of fact-checking before I include information from the book because there are some inaccuracies and fringey theories. Also, it has no index.

Ameghino said his brother Carlos, who was also a paleontologist, had sent him a piece of hide reputedly from a yemish, which he had gotten from a Tehuelche hunter. The hide had tiny bones embedded in it, called osteoderms, which are a feature of giant ground sloths. Ameghino claimed that the yemish was a giant ground sloth, which he named Neomylodon.

Mylodon, as opposed to Ameghino’s Neomylodon, was a 10 foot long, or 3 meter, ground sloth that did indeed have osteoderms embedded in its thick hide. It had long, sharp claws and ate plants, probably dug burrows, and lived throughout Patagonia and probably most of South America. The important thing here is that mylodon remains, including dung as well as dead animals, have been found in caves in Patagonia, and the remains look so fresh that the discoverers thought they were only a few years old. It turns out that they’re all about 10,000 years old, but were preserved by cold, dry conditions in the caves.

So the piece of hide was probably really from a giant ground sloth, but not one that had been alive recently. Most researchers think that the sloths of Patagonia were already extinct when the area was first settled by humans, but discoveries of what looked like recently dead animals with fearsome claws and a hide that couldn’t be pierced with arrows might very well have contributed to stories of local monsters.

But that’s beside the point, because once you get past Ameghino’s obsession with the yemish being a real live giant ground sloth, it’s clear it’s something completely un-slothlike. The exact term yemish isn’t known from any language in Patagonia, but it might be a corruption of hymché, a water monster, or yem’chen, which means water tiger in the Aonikenk language. An even closer match from the same language means sea wolf and is pronounced ee-m’cheen [iü’mchün]. Other languages in the area call the elephant seal yabich, which also sounds similar to yemish. In other words, it’s pretty clear that the yemish is a water animal of some sort.

The sea wolf is what we call a sea lion, a type of huge seal. Sea lions and elephant seals sometimes come up rivers and into freshwater lakes, which may account for some of the numerous lake monster legends in Patagonia. As for the hymché, it may have a natural explanation too that is nevertheless just as mysterious as just calling it a monster.

French naturalist André Tournouer explored Patagonia in 1900, and at one point while following a stream, he and his expedition saw what their guide called a hymché. It was the size of a large puma but with dark fur, rounded head, no visible ears, and pale hair around the eyes. It sank under the water when Tournouer shot at it, and later they found some catlike tracks in the sand along the bank.

From the description, it’s possible that the hymché was a spectacled bear. We learned about it in episode 42. It lives in the Andes Mountains of South America but was formerly much more widespread, and is usually black with lighter markings around the eyes that give it its name. Its ears are small and its head is more rounded than other bears. While it spends most of its time in the treetops, it actually does swim quite well. But as far as we know, spectacled bears don’t live in Patagonia.

So, back to the yemish. According to Ameghino’s 1898 paper, he said the Tehuelche referred to it as the water tiger. Since there is no local word for tiger in South America, since tigers live in Asia, this is probably a translation of the local word for puma. The jaguar did formerly live in Patagonia but was hunted to extinction there over a century ago. The yemish supposedly spent much of its time in the river and dragged horses and other animals into the water when they came down to drink. Its feet were flat, its ears tiny, it had big claws and fangs, and its toes were webbed for swimming. It had shorter legs than a puma but was bigger than one.

This sounds like one specific animal that does live in Patagonia, and it’s not a tiger or any kind of feline at all. It may be an otter. Flat feet with claws and webbed toes? Check. Tiny ears and scary teeth? Check. Longer than a puma but with much shorter legs? Check. Otters don’t kill animals as big as horses, of course, but this could be an exaggeration. Otters will scavenge on freshly dead animals, so the story of a mule that fell off a precipice onto a river bank, and was discovered dead and half-eaten the next morning with strange paw prints all around it, fits with an otter family having an unexpected feast delivered to their doorstep.

Not only that, but some tribes do call otters “river tigers.” Stories of monstrous otter-like animals are common throughout much of South America, not just Patagonia, and are frequently translated as “river tiger.” In Monsters of Patagonia, Whittall wonders why some tribes have two names for the otter in that case, an ordinary name and a name denoting a monster. It’s possible the monster version of the otter either refers to a folkloric beast, an animal like a sea lion that was once seen far from its ordinary home, or two kinds of otter in the area, one bigger and more ferocious than the other.

The southern river otter lives in Patagonia, both in rivers and along the seashore. It’s not especially big, maybe four feet long including the tail, or 1.2 meters. But the rare marine otter also lives along the western and southern coasts of Patagonia. Its scientific name, Lontra felina, means “otter cat, and in Spanish it’s often called gato marino, or sea cat. But the marine otter is small, typically smaller than the river otter and at the very most, around five feet long or 1.5 meters.

But if you remember episode 37, about the dobhar-chu, you may remember the giant otter. It lives in South America north of Patagonia and is now endangered, with only around 5,000 animals left in the wild after being hunted extensively for its fur for decades. It’s protected now, although loss of habitat and poaching are still big problems. It grows to around 6 feet long now, or 1.8 meters, but when it was more common some big males could grow over eight feet long, or 2.5 meters. If in the past an occasional giant otter—twice the length of an ordinary otter—strayed into the rivers of Patagonia, it would definitely be seen as a monster.

Whittall rejects the idea that the yemish is an otter, although he doesn’t mention the giant otter. He also rejects the jaguarondi as the yemish since it’s much too small, although it does like to swim and fish and, as mentioned earlier, it does look remarkably like an otter in many ways. He suggests the yemish might be an unknown giant aquatic rodent, citing as proof the existence of a cow-sized rodent that once lived in Patagonia during the ice age. I’m not convinced. Nothing about the yemish sounds like a rodent. It does sound like an otter, possibly a known otter, possibly a now extinct otter—or, maybe, a giant version of the jaguarondi, also now extinct. But maybe not.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!