Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:41 — 20.9MB)

Subscribe: | More

Thanks to Siya, Zachary, Khalil, and Eilee for their suggestions this week!

The enamel pin Kickstarter goes live on Wednesday, August 14, 2024!!

Further reading:

How spiders breathe under water: Spider’s diving bell performs like gill extracting oxygen from water

Aggressive spiders are quick at making accurate decisions, better at hunting unpredictable preys

Into the Spider-Verse: A young biologist shares her love for eight-legged creatures

A New Genus of Prodidominae Cave Spider from a Paleoburrow and Ferruginous Caves in Brazil

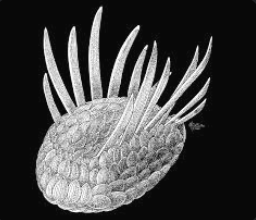

The diving bell spider [photo from this paper]:

Jumping spiders are incredibly cute, even the ones that eat other spiders [photo taken from this excellent site]:

The spoor spider’s web looks like a cloven hoofprint in the sand [photo by JMK – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39988887]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I’m excited this week, because on Wednesday my little Kickstarter to fund getting more enamel pins made goes live, and also we’re talking about some weird and fascinating spiders! Thanks to Siya, Zachary, Khalil, and Eilee for their spider suggestions!

A lot of people are afraid of spiders, but don’t worry. All the spiders in this episode are small and completely harmless unless you are a bug. Also, they probably live very far away from you. Personally, I think most spiders are cute.

Let’s start with a spider suggested by Siya, who pointed out that we don’t actually have very many episodes about spiders. Siya suggested we learn about the diving bell spider, a tiny, remarkable animal that lives in parts of Europe and Asia.

The diving bell spider gets its name because it mostly lives underwater but still needs to breathe air, so it brings air with it into the water. A diving bell made by humans is a structure shaped sort of like a big bell that can be lowered straight down into the water on a cable. If the diving bell doesn’t tip to one side or another, the air inside it stays inside and allows a human diver to take breaths without coming to the surface. A diving bell made by spiders is made of silk but is shaped sort of the same, with an entrance at the bottom. The spider builds its bell among water plants to anchor it and keep it hidden. The spider brings air from the surface to replenish the supply of air inside the bell.

The spider does this by surfacing briefly. Its belly and legs are covered with tiny water-repellent hairs, and after surfacing the hairs trap air, so that when it dives back into the water it’s covered with little silvery bubbles. It swims down to its diving bell and rubs the bubbles off its body, which rise into the bell and are trapped there by the closely woven silk. Then it goes back to the surface for more air.

Once the bell is full of air, the spider only needs to replenish the air supply about once a day under normal circumstances. That’s because the bell itself acts as a sort of external gill. It’s able to absorb oxygen from the water quite efficiently, but it still loses volume slowly because nitrogen from the air diffuses into the water. If not for that, the spider probably wouldn’t need to come to the surface at all.

The diving bell is the spider’s home, especially for the female. Unlike most spiders, the female diving bell spider is much smaller than the male and she hunts differently. The male is an active hunter, swimming quickly to catch tiny animals like mosquito larvae, so he’s large and strong but only has a small diving bell. The female spends most of her time in her diving bell and only swims out to catch animals that come too close, or occasionally to replenish the air in her bell.

When the spider leaves its diving bell to hunt, air bubbles remain trapped on its abdomen, which allows it to breathe while it’s hunting too. Then it can dart back to its bell to get more air or hide if it needs to.

When a male finds a female, he will build his diving bell near hers. If she doesn’t object, he’ll build a little tunnel between the two bells so he can visit her more easily. The pair will mate in the female’s bell and she either attaches her egg sac to the inside wall of her bell or will build a little addition onto her bell that acts as a nursery.

The diving bell spider is gray or black in color and even a big male only grows about 15 mm long, head and body size together. His legs are longer. In the water the spiders appear silver because of the bubbles attached to their bodies.

The spider used to be common throughout much of Asia and Europe, but its numbers are in decline due to pollution and habitat loss, since it needs slow-moving streams, ponds, marshes, and other clean freshwater with aquatic plants to survive. It will bite if it feels threatened and some people claim that its bite is painful and leads to symptoms like fever, but there’s not a lot of evidence for the bite being dangerous or even all that painful to humans.

Next, Zachary suggested the Portia spider, and pointed out that it demonstrates “uniquely intelligent hunting.” If it weren’t such a tiny spider, it might be scary because it’s so smart. Fortunately for humans, not only is it even smaller than the diving bell spider, with even a big female no more than 10 mm long counting her head and body together, it’s a spider that eats other spiders.

There are 17 species of portia spider currently known, living in parts of Africa, Asia, Australia, and a lot of islands in southeast Asia. It’s a type of jumping spider and can jump as much as 6 inches, or 15 cm, from a complete standstill. It’s mostly brown with mottled darker and lighter markings that make it look like a bit of dead leaf when it’s standing still. It also has flaps on its legs that help it look less like a spider too.

Looking like a bit of dead leaf helps the Portia spider keep from being eaten by birds and frogs, but it also helps it when hunting prey spiders. Unlike almost all other spiders, the portia spider can travel on the webs of pretty much any species of spider without getting stuck. It will creep into another spider’s web and sneak up on it very slowly, or pretend to be a stuck insect to lure it closer. Most spiders don’t see very well, so they don’t identify the portia as a predatory spider. They either think it’s just a leaf stuck in its web or an insect, until it’s too late.

The portia spider will try many different ways to catch a spider. If one doesn’t work it will use another method, and will continue to try new methods and combinations of methods until it outsmarts the prey spider and can jump on it. The methods it uses can be incredibly complex and often require the portia spider to move away from the prey spider or even out of view of it, but it can remember exactly where the prey spider is and what it wants to do to approach it. Remember, this is an animal about the size of one of your fingernails. It has a teeny brain!

In captive studies, portia spiders are observed to be more or less aggressive depending on the individual. The more aggressive spiders tend to do a better job hunting prey with unpredictable behaviors, while the less aggressive spiders are more patient.

When the portia spider walks, it does so arrhythmically, which helps it imitate a dead leaf being moved by the wind. Some spiders are so nervous of portia spiders that if they sense an arrhythmic movement on their web, even if it’s not a portia spider, they’ll run and hide. For that matter, the portia spider will take advantage of wind and other natural occurrences to get closer to their prey.

In addition to active hunting, female portia spiders will also build funnel webs to catch insects. You know, kind of a side hustle. Any portia spider will spin a simple web to hide behind to rest. Portia spiders are also social, sharing food and even living together.

When the male portia spider wants to find a mate, he spins a little web near a female’s web and shakes his legs to attract the female. If she likes him, she’ll drum on his web to let him know. However, in most species, mating is a death sentence for the male. Remember how last week we talked about the praying mantis and how sometimes the female will actually eat the male after or even during mating? Well, that’s true for most species of portia spider too. In some species the female almost always eats the male. He gets to pass his genes along to the next generation, and she gets a good meal to help her grow healthy eggs.

Next, Leo’s friend Khalil suggested the wandering spider. This is the name given to a big family of spiders that live throughout much of the world. Most of them are quite large and look like tarantulas, especially the Brazilian wandering spider, also called the banana spider. It can have a head and body length of two inches, or about 5 cm, but a legspan of up to 7 inches, or 18 cm. That’s a lot of spider, and this week we’re talking about small spiders, but let’s take a quick detour and find out if the banana spider really is sometimes found in bunches of bananas sold in stores.

The banana spider lives in Brazil and other parts of northern South America and Central America, and that’s where a lot of the world’s bananas are grown. I couldn’t find any good estimates of how many bananas are exported every year, but the United States is the biggest importer of bananas. I’m going to switch completely to imperial measurements for a moment because the amounts I’m about to talk about make no logical sense anyway. About four bananas add up to one pound of weight, and 2000 pounds make up one ton. That means one ton of bananas is approximately 8,000 bananas. In 2023, over 5 million tons of bananas were imported to the United States. That is at least 40 billion bananas!

In comparison, no one seems to be tracking how many spiders are found hiding in banana bunches, but one paper from 2014 documented that of 135 spiders submitted to the scientists for study as having been found in all international shipments, of bananas and everything else, only seven were actually banana spiders. The rest were other kinds of spider, most of them completely harmless. When one is found it gets into the news because it’s so rare.

Spiders don’t live inside the banana peel anyway, and they don’t eat bananas. It’s just that bunches of bananas make good hiding places, and the spiders don’t know that people are going to chop the whole bunch down without even noticing a hidden spider. By the time the bananas get to the store, the big bunches have been cut up into little bunches of a few bananas each, which isn’t a great hiding space for a big spider. So your bananas are safe.

Anyway, the smallest wandering spider is probably in the genus Acanthonoctenus, which are native to Central and South America. A big female only grows about 15 mm long, head and body measured together, although her legspan is much larger. There are other wandering spiders with about the same body size in various genera. The problem is, there are hundreds of known species of wandering spider and probably a lot more that haven’t been discovered yet, but not a lot of people are studying them. We don’t know a whole lot about the smallest species because they’re harder to find and therefore harder to study. Many species have only ever had a single specimen collected. So if you want to become an arachnologist, you might look into wandering spiders for your specialization. Many of them are absolutely gorgeous, with striped legs and bright colors.

Like some other spiders, many Acanthonoctenus spiders will hide on a leaf or tree trunk by lying flat and stretching four of its legs out in front of it and the other four legs behind it. This makes it less spider shaped when a bird or lizard is looking around trying to find a snack.

Next, Eilee suggested the spoor spider, the name for Seothyra, a genus of spiders that live in sandy areas in southern Africa. Females grow up to 15 mm long, head and body together, while males grow up to 12 mm long and are usually considerably smaller than the females. The female can be brown, gray, or tan and may have stripes on her abdomen, while the male is more brightly colored. He can be yellow and black with a rusty-red head, sometimes with white spots on his abdomen.

The male spends most of his time running around finding food, and since he looks a lot like a type of wasp called the velvet ant, he’s in less danger than you’d think considering he’s active during the day. The female spends almost all of her life in an elaborate web that she builds into the sand.

The female excavates a burrow in the sand that can be as much as 6 inches deep, or 15 cm, lined with silk to keep it from collapsing. She gets sand out of the burrow as she constructs it by spinning little silk bags around the sand to carry it out. She leaves the bags of sand around the entrance, and once the burrow is finished, she incorporates the sandbags into the web itself. She spins web sheets and mixes them with sand to make mats around the burrow’s opening, which is hidden, and the spider can lift the web sheets to go in and out. Ideally she stays in the same burrow her whole life, repairing it as needed, because while it’s not an especially big web, it takes her a lot of energy to make.

The female puts sticky strands of silk around the edges of the web, then retreats to the underside of the web sheet or into the burrow if it’s too hot. When an insect gets stuck on the silk, she darts out and kills it, then takes it into her burrow to eat. Mostly she eats ants.

The name spoor spider, also called buck spoor spider, comes from the shape of the female’s web. In most species, the web sheet has two sides in a shallow depression in the sand. Since the web is also covered with and incorporates sand to hide it, the little depression with a rounded double shape at the bottom looks an awful lot like the footprint of an animal with a cloven hoof. The word “spoor” is a term indicating an animal’s track.

The spoor spider female only produces one egg sac in her life, and takes care of it in her burrow until the babies hatch. Then she takes care of the babies by gradually liquefying her own internal organs and regurgitating the liquid so the babies can eat it. When all her organs are gone she dies, naturally, and the babies eat the remainder of her body before venturing out into the world on their own.

Fossilized web sheets very similar to the modern spoor spider’s web have been found dating back 16 million years. Most spiderwebs can’t fossilize, but most spiderwebs aren’t built partly out of sand.

Finally, let’s finish up with a newly discovered spider from South America. I learned about it from Zeke Darwin, a science teacher who makes really interesting videos on TikTok. The spider has been described as a new species, named Paleotoca, and was discovered in Brazil. We know very little about it so far so I don’t have much information to share, but it’s so interesting that I just had to include it.

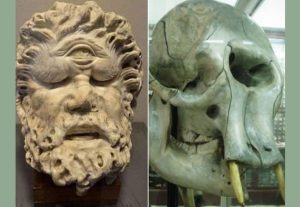

Paleotoca is pale yellow, although its abdomen has very little pigmentation, and its head and body together measure barely 2 mm. It doesn’t have eyes. You might be able to guess where it lives from its lack of eyes and lack of pigment in its body, but I bet I’m going to surprise you anyway. Paleotoca does live in caves, but technically these caves are burrows. It’s just that the burrows where it lives are extremely large, dug into the sides of hills thousands of years ago by giant ground sloths before they went extinct.

Luckily for the spider, there are also some natural caves in the area and at least one of the spiders has been found living in one. So little Paleotoca isn’t in danger of going extinct just because the burrow-builders are gone.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!