Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:14 — 20.0MB)

Thanks to Pranav for suggesting this week’s massive topic!

Further reading:

When did the Isthmus of Panama form between North and South America?

Florida fossil porcupine solves a prickly dilemma 10-million years in the making

Evidence for butchery of giant armadillo-like mammals in Argentina 21,000 years ago

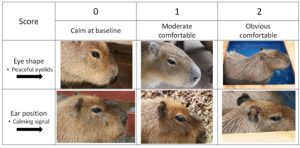

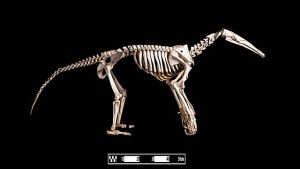

Glyptodonts were big armored mammals:

The porcupine, our big pointy friend:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week, at long last, we’re going to learn about the great American interchange, also called the great American biotic interchange. Pranav suggested this topic ages ago, and I’ve been wanting to cover it ever since but never have gotten around to it until now. While this episode finishes off 2024 for us, it’s the start of a new series I have planned for 2025, where every so often we’ll learn about the animals of a particular place, either a modern country or a particular time in history for a whole continent.

These days, North and South America are linked by a narrow landmass generally referred to as Central America. At its narrowest point, Central America is only about 51 miles wide, or 82 km. That’s where the Panama Canal was built so that ships could get from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific and vice versa without having to go all around South America.

It wasn’t all that long ago, geologically speaking, that North and South America were completely separated, and they had been separated for millions of years. South America was part of the supercontinent Gondwana, while North America was part of the supercontinent Laurasia.

We’ve talked about continental drift before, which basically means that the land we know and love on the earth today moves very, very slowly over the years. The earth’s crust, whether it’s underwater or above water, is separated into what are called continental plates, or tectonic plates. You can think of them as gigantic pieces of a broken slab of rock, all of the pieces resting on a big pile of really dense jelly. The jelly in this case is molten rock that’s moving because of its own heat and the rotation of the earth and lots of other forces. Sometimes two pieces of the slab meet and crunch together, which forms mountains as the land is forced upward, while sometimes two pieces tear apart, which forms deep rift lakes and eventually oceans. All this movement happens incredibly slowly from a human’s point of view–like, your fingernails grow faster than most continental plates move. But even if a plate only moves 5 millimeters a year, after a million years it’s traveled 5 kilometers.

Anyway, the supercontinent Gondwana was made up of plates that are now South America, Africa, Australia, Antarctica, and a few others. You can see how the east coast of South America fits up against the west coast of Africa like two puzzle pieces. Gondwana actually formed around 800 million years ago, then became part of the even bigger supercontinent Pangaea, and when Pangaea broke apart around 200 million years ago, Gondwana and Laurasia were completely separate. North America was part of Laurasia. But Gondwana continued to break apart. Africa and Australia traveled far away from South America as molten lava filled the rift areas and helped push the plates apart, forming the South Atlantic Ocean. Antarctica settled onto the south pole and India traveled past Africa until it crashed into Eurasia. By about 30 million years ago, South America was a gigantic island.

It’s easy to think that all this happened just like taking puzzle pieces apart, but it was an incredibly long, complicated process that we don’t fully understand. To explain just how complicated it is, let’s talk for a moment about marsupials.

Marsupials are mammals that are born very early and finish developing outside of the mother’s womb, usually in a special pouch. Kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, and Tasmanian devils are all marsupials, and all from Australia. But marsupials didn’t originate in Australia and are still present in other parts of the world.

The oldest known marsupial appears in North America about 65 million years ago, which was part of the other supercontinent on Earth at the same time as Gondwana, called Laurasia. About the time marsupials were spreading out across Laurasia, from North America all the way to China, Laurasia and Gondwana were connected for a while along the northern edge of South America. Animals were able to cross from Laurasia to Gondwana before the two supercontinents split apart again. Marsupials spread from Laurasia and across Gondwana before the continent of Australia separated about 50 million years ago. Marsupials did so well in Australia that researchers think that before Australia was fully separated from Gondwana, marsupials actually started spreading back out of Australia and into Gondwana again.

While marsupials were doing extremely well in Australia, in South America, birds were the dominant vertebrate for a long time. We talked about terror birds in episode 202. Phorusrhacidae is the name for a family of flightless birds that lived from about 62 million years ago to a little under 2 million years ago. They were carnivores and various species ranged in size from about 3 feet tall to 10 feet tall, or 1 to 3 meters, and had long, strong legs that made them fast runners. The terror bird also had a long, strong neck, a sharp hooked beak, and sharp talons on its toes.

Other birds in North America were likewise huge, but could fly. Those were the teratorns, which are related to modern New World vultures. Since they had huge wingspans and could fly long distances easily, they could just fly between North and South America if they wanted to, so teratorns were found on both continents starting around 25 million years ago. They only went extinct around 10,000 years ago. The largest species known, Argentavis magnificens, lived in South America around six million years ago. It’s estimated to have a wingspan of at least 20 feet, or 6 meters, and possibly as much as 26 feet, or 8 meters. That’s the size of a small aircraft.

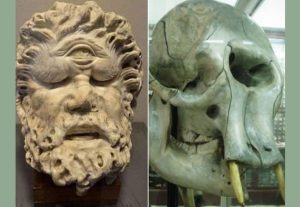

In addition to giant predator birds, South America had crocodilians that could grow over 30 feet long, or 9 meters, and possibly as much as 40 feet long, or 12 meters. And, of course, it had ancestral forms of animals we’re familiar with today, like sloths, anteaters, armadillos, opossums, monkeys, capybaras, and lots more. Some of these were incredibly large too, like the giant ground sloth that was as big as an African elephant and the glyptodon that was related to modern armadillos. Glyptodon had a huge bony carapace and rings of bony plates on the end of its thick tail that made it into a club-like weapon, and it was the size of a car. Both the giant ground sloths and the glyptodonts were plant-eaters, as were the notoungulates.

The notoungulates are an extinct order of hoofed animals that lived throughout South America. They were probably most closely related to rhinoceroses, horses, and other odd-toed ungulates, but they’re completely extinct with no living descendants. Some were tiny and actually looked and probably acted more like rabbits than horses, while others were massive. We talked about trigodon in episode 387, and it and many of its close relations in the family Toxodontidae were the size and build of a modern rhinoceros. Trigodon even had a small horn on its forehead. A closely related group, Litopterna, is also a completely extinct order of ungulates, which were mostly smaller and more deer-like than the notoungulates.

The Pleistocene is also called the ice age, but it’s more accurate to say that it was a series of ice ages with long periods of warmer weather in between–tens of thousands of years of warmer climate, then a colder cycle that lasted tens of thousands more years. When the glaciers were at their maximum, with ice sheets covering some parts of the world over a mile thick, or a kilometer and a half, sea levels were considerably lower because so much of the world’s water was frozen solid. That exposed more land that would ordinarily be partially or completely underwater, and it also led to a dryer climate overall. At the same time, volcanic activity in the ocean separating what is now North and South America had been building up volcanic islands for millions of years. All these factors and more combined to form the Isthmus of Panama, also called Central America, that is basically a land bridge connecting the two continents.

This started around 5 million years ago and the isthmus was fully formed by about 3 million years ago, or at least that’s the most accepted theory right now. A 2016 study suggested that the land bridge started forming far earlier than that, possibly as early as 23 million years ago, possibly 6 to 15 million years. Studies are ongoing to learn more about the timeline.

What we do know is that once the land bridge opened up, animals started migrating into this new area. Animals from North America migrated south, and animals from South America migrated north. It didn’t happen all at once, of course. It was a slow process as various animal populations expanded into Central America over generations. Some animals had trouble with the climate or couldn’t find the right foods, while others did really well and expanded rapidly.

The ancestors of some animals that made it to North America and are still around include the Virginia opossum, the armadillo, and the porcupine. Meanwhile, the ancestors of llamas, horses, tapirs, deer, canids, felids, coatis, and bears traveled to South America and are still there, along with many smaller animals like rodents. Many other animals migrated, survived for a while, but later went extinct. This included a type of elephant called the gomphothere and saber-toothed cats that migrated south, while ground sloths, terror birds, glyptodonts, capybaras, and even a type of notoungulate migrated north.

You may notice that more animals that migrated south survived into modern times. South America was much warmer overall than North America, and most animals that traveled north had trouble adapting to a colder climate and competing with animals that were already well-adapted to the cold. Animals traveling south encountered warmer climates early, and if they were able to tolerate hot weather they didn’t have to worry about any climactic shocks on the rest of their journey south. As a result, North American animals were able to establish themselves in larger numbers, which helped them adapt even faster since more babies were being born and surviving.

One South America to North America success story is the porcupine. Porcupines are rodents, and there are two groups, referred to as old world and new world porcupines. Those are not great terms but that’s what we have right now. The old world porcupines are found in parts of Africa, Asia, and Italy, although they were once more widespread in Europe, while new world porcupines are found in parts of North and South America. Old world porcupines live exclusively on the ground and are larger overall than new world ones, which spend a lot of time in trees. Surprisingly, the two groups are only distantly related. They evolved spines separately. They’re also only very distantly related to hedgehogs.

The one thing everyone knows about the porcupine is that it has quills, long sharp spines that make hedgehog spines look positively modest. Porcupine quills are dangerous. They’re modified hairs, and actual hair grows in between the quills, but they’re covered in strong keratin plates and are extremely sharp. They also come out easily and regrow all the time. A porcupine can hold its spines down flat so it won’t hurt another porcupine, which is what they do when they mate.

Only one species of porcupine lives in North America, called the North American porcupine. It lives throughout much of the northern and western part of the continent, from way up in the far north of Canada down to central Mexico, although it doesn’t live in most of the southeast. We don’t know if the North American porcupine developed after South American porcupines migrated north, or if it developed much earlier, around 10 million years ago. Porcupine experts have been arguing about this for years, because there aren’t very many porcupine fossils to study.

Then a nearly complete fossil porcupine was discovered in Florida. It was such a big deal that the scientific team that discovered it decided to create an entire college course for paleontology students to help study the specimen. The resulting study was published in May of 2024, and the results suggest that the North American porcupine evolved a lot longer ago than the Isthmus of Panama formed.

The North American porcupine had to change a lot to withstand the intense cold when its ancestors were tropical animals. The North American porcupine is very different from its South American cousins. It spends less time in trees and doesn’t have a prehensile tail, it eats a lot of bark instead of mostly leaves, and it has thick insulating fur between its quills. The fossilized specimen discovered in Florida still had a prehensile tail and didn’t have the strong jaw it needed to gnaw bark off trees, but it already showed a lot of adaptations that are seen in the North American porcupine but not in South American species.

Ultimately, of course, a lot of large animals went extinct around 12,000 to 10,000 years ago, the end of the Pleistocene. Animals like mammoths that were well-adapted to cold died out as the climate warmed, and so did their predators, like dire wolves and the American lion. The notoungulates and other megaherbivores in South America went extinct too.

One animal that I haven’t mentioned yet that migrated south successfully was Homo sapiens. Maybe you’ve heard of them. Until very recently, the accepted time frame for humans migrating into South America was about 16,000 years ago, although not everyone agreed. But in July of 2024, a new study pushed that date back to 21,000 years ago.

The study examined glyptodont fossils found in what is now Argentina. The fossils were found on the banks of a river and were determined to show butchering marks from stone tools. The bones were dated to almost 21,000 years ago, which means that humans probably moved into South America a lot earlier than that. It takes time to travel from Central America down to Argentina.

One detail most people don’t know about when it comes to the Great American Interchange is how marine animals were affected. It was exactly opposite for them. Instead of a new land to explore, which caused very different animals to encounter each other for the first time, the Isthmus of Panama cut populations of marine animals from each other. They’ve been evolving separately ever since. So I guess whether a land bridge is bad or good depends on your point of view.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!