Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:30 — 13.1MB)

This week let’s venture into the ocean and learn about the fin whale!

Further reading:

The songs of fin whales offer new avenue for seismic studies of the oceanic crust

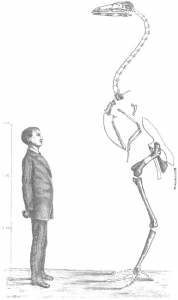

The fin whale can hold a whole lot of water in its mouth (illustration from the second article linked above):

A fin whale underwater. Look at that massive tail. That’s pure muscle:

A fin whale above water. It’s like a torpedo:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s been too long since we had an episode about whales. Yes, okay, two weeks ago we talked about a couple of newly discovered whales, but I want to really learn about a particular whale. So this week, let’s look at the fin whale.

The fin whale is a baleen whale that’s only a little less enormous than the blue whale. The longest fin whale ever reliably measured was 85 feet long, or just a hair shy of 26 meters, but there are reports of fin whales that are almost 90 feet long, or a bit over 27 meters. An average American school bus is half that length, so a fin whale is as long as two school buses. Even a newborn fin whale calf is enormous, as much as 21 feet long, or 6.5 meters. Females are on average larger than males.

It’s a long, slender whale that’s sometimes called “the greyhound of the sea,” because it’s also really fast. It can swim up to 29 mph, or 46 km/hour, and possibly faster. If that doesn’t sound too fast, consider that the Olympic gold-medal swimmer Michael Phelps topped out at about 4.7 miles per hour, or 7.6 km/h.

Like other baleen whales, the fin whale has a pair of blowholes instead of just one. On its underside, it has up to 100 grooves that extend from its chin down to its belly button. Yes, whales have belly buttons. They’re placental mammals, and all mammals have belly buttons because that’s where the umbilical cord is attached when a developing baby is in its mother’s womb. I don’t know what a whale’s belly button looks like. Also, the proper term for belly button is navel, and if you’re wondering, that’s where navel oranges get their name, because they have that weird thing on one end that looks like a belly button. It’s not, though. I don’t know what it is. You’ll have to find a podcast called Strange Plants to explain it.

Anyway, the grooves on the fin whale’s underside act as pleats, or accordion folds. Other baleen whales have these pleats too. A baleen whale eats tiny animals that it filters out of the water through its baleen plates, which are keratin structures in its mouth that take the place of teeth. The baleen is tough but thin and hangs down from the upper jaw. It’s white and looks sort of like a bunch of bristles at the end of a broom. The whale opens its mouth wide while lunging forward or downward, which fills its huge mouth with astounding amounts of water. As water enters the mouth, the skin stretches to hold even more, until the grooves completely flatten out. The water it can hold in its mouth is about equal to the size of a school bus.

Technically, though, a lot of that water isn’t in the whale’s mouth. It’s in a big pocket between the body wall and the blubber underneath the skin. The ballooning out of the pocket stretches the nerves in the mouth and tongue to more than twice their length, and then the nerves have to fold back up tightly after the water is pushed out. The nerves fold in a complicated double layer to minimize damage during all this stretching.

After the whale fills its mouth with water, it closes its jaws, pushing its enormous tongue up, and forces all that water out through the baleen. Any tiny animals like krill, copepods, small squid, small fish, and so on, get trapped in the baleen. It can then swallow all that food and open its mouth for another big bite. Even more amazing, this whole operation, from opening its mouth to swallowing the food, only takes six to ten seconds.

Because it only eats small animals, the fin whale’s esophagus (which is the inside part of the throat) is actually quite narrow considering what a huge animal it is. In other words, it could not possibly swallow a human, in case you were worried. I was worried. If you did end up in a fin whale’s mouth, it would just spit you back out.

Baleen whales have a sensory organ on the chin that’s found in no other animal. It’s about the size of a grapefruit and situated between the tips of the jaws. It probably helps the whale determine how much potential food is in the water, which saves it from wasting time and energy gulping in water and filtering it out when there’s nothing much to eat.

The fin whale looks a lot like the blue whale and the two species are closely related, so much so that they sometimes interbreed and produce hybrid babies. It usually lives in small groups of up to around 10 individuals and a female fin whale has one baby every two or three years. It probably migrates seasonally to new feeding grounds, but we don’t actually know a whole lot about where it goes and whether all fin whales migrate.

Fin whales have extremely loud vocalizations, but most humans would barely be able to hear them, or wouldn’t be able to hear them at all, because they’re at the very bottom or below the range of sounds that the human ear can detect. The calls can be up to 188 decibels, a measure of loudness, which may be the loudest sounds made by any animal alive today. Technically the blue whale is louder, at 190 decibels, but on average the fin whale is louder. In comparison, a jet plane taking off is measured at 150 decibels. Of course, sound through water is different from sound through air, because water is much denser. A better comparison is with an offshore drill rig at 185 decibels or a supertanker ship at 190 decibels. The fin whale is about as loud as both, although of course the fin whale doesn’t make those noises all the time like drill rigs and ships do. The male fin whale makes short pulses of sound that last a second or two in specific patterns, which he repeats sometimes for days. Since the sounds travel long distances underwater, researchers think a female can hear a male’s calls and follow the sound so she can find him to mate. Of course, this means that females may have trouble finding a male these days since the ocean is full of noise from human-made things like offshore drill rigs and supertanker ships.

The fin whale is not only one of the loudest animals known, its vocalizations are among the lowest in frequency of any animal ever recorded. It turns out that this combination has a surprising benefit to human knowledge in a very specific way.

In an article published in Science just a few days ago as this episode goes live in February of 2021, a team of scientists discovered that fin whale vocalizations can help with seismic imaging of the oceanic crust.

The oceanic crust isn’t just the sea floor but what the earth below the sea floor is made up of. Scientists measure the reflections of a sound wave, and since sound waves travel at different speeds through different materials, and bounce off various types of rocks and other structures at different speeds and angles, the reflections can tell us a lot. Scientists use sensitive seismometers on the ocean floor to read the reflections. The problem is how to get the sound wave in the first place. Researchers usually use a giant air gun to make sound waves, but not only can this be dangerous to ocean life because it’s so loud, it’s also expensive and can’t be used in all areas.

But the fin whale does almost as good a job as an air gun. A pair of researchers studying earthquakes off the Oregon coast in North America noticed that when fin whales were around, their seismometers picked up extra signals. They figured out that the signals were actually from the fin whales’ vocalizations, and were surprised to find that the reflections matched those from the air gun sound waves. As an added benefit, the researchers could pinpoint exactly where each whale was since its signals were picked up by multiple seismometers.

Fin whale vocalizations are at the perfect frequency and strength for sound waves to travel through the ocean floor and be picked up by the seismometers. Best of all, fin whales live throughout almost all of the world’s oceans, including places where air guns can’t be used. Researchers just have to put the seismometers in place and the whales produce as many sound waves as the scientists need.

Because the fin whale makes such low-frequency noises, its hearing is different from other animals’. Big as a fin whale is, the low-frequency vocalizations it makes actually form a sound wave that’s longer than its body, which means the whale actually can’t hear it through its ears. But for a long time, scientists weren’t sure how the fin whale and other big baleen whales could hear those sounds.

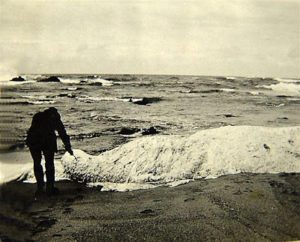

Then, in 2003, a fin whale beached in California and died despite attempts to save it. Scientists were allowed to collect the body for research, and they took the head to an X-ray CT scanner designed for rocket motors to get a 3D image they could study. It turns out that the fin whale’s skull has acoustic properties that makes it sensitive to low frequency sounds and actually amplifies the sound waves as the bones of the skull vibrate. So fin whales hear each other with their skull bones instead of their ears.

Absolutely nothing can top that amazing fact, so that’s the end of this episode.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!