Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:13 — 15.2MB)

It’s been too long since we discussed whales, so this week let’s learn about how whales evolved and some especially strange or mysterious whales!

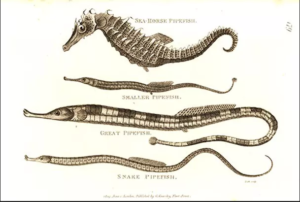

Pakicetus was probably kind of piggy-looking, but with a crocodile snout:

Protocetids were more actually whale-like but still not all that whale-like:

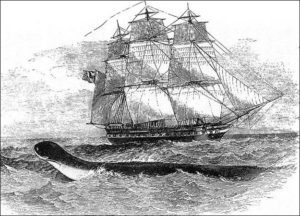

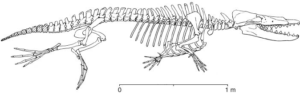

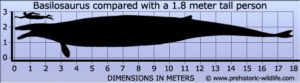

Now we’re getting whaley! Here’s basilosaurus, with a dinosaur name because the guy who found it thought it was a reptile:

Here’s the skull of a male strap-toothed whale (left). Those flat strips are the teeth:

Another view. See how the teeth grow up from the lower jaw and around the upper jaw?

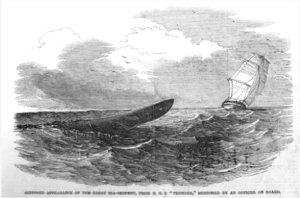

A dead pygmy right whale:

The walrus whale may have looked sort of like this:

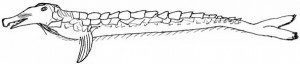

The half-beak porpoise had a chin that just would not quit:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s topic is weird whales and some of their relations. If you think about it, all whales are weird, but these are the weirdest whales we know of. Some are living, some are extinct, and some…are mysteries.

Whales, dolphins, and porpoises are most closely related to—wait for it—HIPPOPOTAMUSES. About 48 million years ago an ancestor of both modern hippos and whales lived in Asia. It’s called Inodhyus and it was about the size of a cat, but looked more pig-like. It was at least partially aquatic, probably as a way to hide from predators, but it was an omnivore that probably did most of its hunting and foraging on land.

The earliest whale is generally accepted to be Pakicetus. It lived around the same time as Inodhyus and its fossils have been found in what is now Pakistan and India. It was about the size of a big dog, but with a long, thick tail. Its skull was elongated, something like a short-snouted crocodile with big sharp triangular teeth. It had upward-facing eyes like a crocodile or hippo, and it also had four long, fairly thin legs. It probably hunted on both land and in shallow water, and like the hippo it probably didn’t have much hair.

That doesn’t sound much like a whale, but it had features that only appear in whales. These features became more and more exaggerated in its descendants. At first, these ancestral whales looked more like mammalian crocodiles. It’s not until Protocetids evolved around 45 million years ago that they started to look recognizably like whales. Some protocetids lived in shallow oceans throughout the world but probably still gave birth on land, while others were more amphibious and lived along the coasts, where they probably hunted both in and out of water. But they had nostrils that had migrated farther back up their snouts, although they weren’t blowholes just yet, reduced limbs, and may have had flukes on their large tails. But they still weren’t totally whale-like. One protocetid, Rodhocetus balochistanensis, still had nail-like hooves on its forefeet.

By around 41 million years ago, the basilosaurids and their close relations had evolved, and were fully aquatic. They lived in the oceans throughout the tropics and subtropics, and their nostrils had moved almost to the location of modern whales’ blowholes. Their forelegs were basically flippers with little fingers, their hind legs had almost disappeared, and they had tail flukes. They were also much bigger than their ancestors. Basilosaurus could grow up to 60 feet long, or 18 meters, and probably looked more like a gigantic eel than a modern whale. It was long and relatively thin, and may have mostly lived at the ocean’s surface, swimming more like an eel or fish than a whale. It ate fish and sharks. SHARKS.

So when did whales develop the ability to echolocate? Researchers think it happened roughly 34 million years ago, which also happens to be about the same time that baleen whales and toothed whales started to develop separately. Echolocation probably evolved to help whales track hard-shelled mollusks called nautiloids. By 10 million years ago, though, nautiloids were on the decline and mostly lived around reefs. Whales had to shift their focus to soft-bodied prey like squid, which meant their sonar abilities had to become more and more refined. Toothed whales echolocate, while baleen whales probably do not. Researchers aren’t 100% sure, but if baleen whales do use echolocation, it’s limited in scope and the whales probably mostly use it for sensing obstacles like ice or the sea floor.

Baleen whales are the ones that communicate with song, although the really elaborate songs are from humpback and bowhead whales. Of those species, humpback songs are structured and orderly, while bowhead whale song is more free-form. But humpback songs do change, and researchers have discovered that they spread among a population of whales the same way popular songs spread through human populations. This is what they sound like, by the way. A snippet of humpback song is first, then a snippet of bowhead song.

[examples of humpback and bowhead]

So now we’ve got a basic understanding of how whales evolved. Now let’s take a look at some of the weirder whales we know about. We’ll start with a living one, the strap-toothed whale. It’s one of 20-odd species of mesoplodont, or beaked whale, and we don’t know a whole lot about any of them. The strap-toothed whale is the longest beaked whale at 20 feet long, or 6.2 meters.

The strap-toothed whale lives in cold waters in the southern hemisphere. It’s rarely seen, probably since it lives in areas that aren’t very well traveled by humans. It mostly eats squid. Females are usually a little bigger than males, and adults are mostly black with white markings on the throat and back.

The weird thing about this whale is its teeth. Male beaked whales all have a pair of weird teeth, usually tusk-like, which they use to fight each other, but strap-toothed whales take the weird teeth deal to the extreme. As a male grows, two of its teeth grow up from the lower jaw and backwards, curving around the upper jaw until the whale can’t open its mouth very far and can only eat small prey. The teeth can grow a foot long, or 30 cm, and have small projections that cause more damage in fights with other males.

Most of what we know about the strap-toothed whale comes from whales that have been stranded on land and died. Males don’t seem to have any trouble getting enough to eat, and researchers think they may use suction to pull prey into their mouths. Other beaked whales are known to feed this way.

All beaked whales are deep divers, generally live in remote parts of the world’s oceans, and are rarely seen. In other words, we don’t know for sure how many species there really are. In 1963, a dead beaked whale washed ashore in Sri Lanka. At first it was described as a new species, but a few years later other researchers decided it was a ginkgo-toothed whale, which had also only been discovered in 1963. Male ginkgo-toothed whales have a pair of tusks shaped like ginkgo leaves, but they don’t appear to use them to fight each other. But a study published in 2014 determined that the 1963 whale, along with six others found stranded in various areas, belong to a new species. It’s never been seen alive. Neither has the ginkgo-toothed whale.

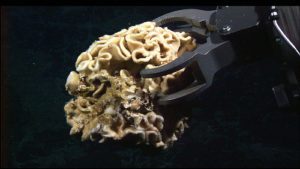

The pygmy right whale is a baleen whale, but it’s another one we know very little about. It lives in the southern hemisphere. Despite its name, it isn’t closely related to the right whale. It’s small for a baleen whale, around 21 feet long, or 6.5 meters, and it’s dark gray above and lighter gray or white underneath. Its sickle-shaped dorsal fin is small and doesn’t always show when the whale surfaces to breathe. It feeds mostly on tiny crustaceans like copepods, and probably doesn’t dive very deeply considering its relatively small heart and lungs.

The pygmy right whale was first described in 1846 from bones and baleen. Later studies revealed that it’s really different from other baleen whales, with more pairs of ribs and other physical differences. It also doesn’t seem to act like other baleen whales. It doesn’t breach, slap its tail, or show its flukes when it dives. It doesn’t even swim the same way other whales swim. Other whales swim by flexing the tail, leaving the body stable, but the pygmy right whale flexes its whole body from head to tail. It seems to be a fairly solitary whale, usually seen singly or in pairs, although sometimes one will travel with other whale species. In 1992, though, 80 pygmy right whales were seen together off the coast of southwest Australia. Fewer than 200 of the whales have been spotted alive, including those 80, so we have no idea how rare they are.

It wasn’t until 2012 that the pygmy right whale’s differences were explained. It turns out that it’s not that closely related to other baleen whales. Instead, it’s the descendant of a family of whales called cetotheres—but until then, researchers thought cetotheres had gone extinct completely around two million years ago. Not only that, it turns out that at least one other cetothere survived much later than two million years ago, with new fossils dated to only 700,000 years ago. But that particular whale, Herpetocetus, had a weird jaw joint that kept it from being able to open its mouth very far. It and the strap-toothed whale should start a club.

Sometimes whale fossils are found in unexpected places, which helps give us an idea of what the land and ocean was like at the time. For instance, fossils of an extinct beaked whale known as a Turkana ziphiid was found in Kenya in 1963, in a desert region 460 miles inland, or 740 kilometers. The fossil is 17 million years old. So how did it get so far inland?

It turns out that at the time, that part of east Africa was near sea level and grown up with forests. The fossil was found in river deposits, so the whale probably swam into the mouth of a river, got confused and kept going, and then couldn’t turn around. It kept swimming until it became stranded and died. Because of the finding, researchers know that 17 million years ago, the uplift of East Africa had not yet begun, or if it had it hadn’t yet made much progress. The uplift, of course, is what prompted our own ancestors to start walking upright, as their forest home slowly became grassland.

As an interesting aside, the fossil was stored at the Smithsonian, but at some point, like so many other fascinating items, it disappeared. Paleontologist Louis Jacobs spent 30 years trying to find it, and eventually located it at Harvard University in 2011. After he finished studying it, he donated it to the National Museum of Kenya.

More whale fossils were uncovered in 2010 in the Atacama Desert in Chile—in this case, over 75 skeletons, many in excellent condition, dated to between 2 and 7 million years ago. Researchers think they’re the result of toxic algae blooms that killed the whales, which then washed ashore. Over 40 were various types of baleen whales. Other fossils found in the same deposit include a sperm whale, marine sloths, and a tusked dolphin known as a walrus whale.

The walrus whale lived in the Pacific Ocean around 10 million years ago, and while it’s considered a dolphin, it’s actually more closely related to narwhals. But it probably looked more like a walrus than either. Unlike most whales, it had a flexible neck. It also had a face like a walrus. You know, flattish with tusks sticking down. It probably ate molluscs. But the right tusk was much longer than the left one, possibly in males only. In the case of one species of walrus whale, one specimen’s left tusk was about 10 inches long, or 25 cm, while its right tusk was over four feet long, or 1.35 meters. Some researchers suggest that the whale swam with its head bent so that the long tusk lay along the body. Possibly it only used it for display, either to show off for females or to fight other males. But we don’t know for sure.

Speaking of narwhals, if you were hoping to hear about them, you’ll need to go way back to episode five, about the unicorn. I talk about the narwhal a lot in that episode. The narwhal happens to be one of the best animals. A lot of people think the narwhal isn’t a real animal, that it’s made up like a unicorn. In fact, about a week ago, I was talking to a coworker and the subject of narwhals came up. She actually did not realize it was a real animal. Nope, it’s real, and that horn is real, but it’s actually a tusk rather than a horn. It grows through the whale’s upper lip, not its forehead. In another weird coincidence, this afternoon when I was about to sit down and record this episode, a friend sent me a link to an article that had some narwhal sounds. So we’re not really talking about narwhals in this episode, but hey, this is what they sound like.

[narwhal calls]

Another weird whale is the halfbeak porpoise, or skimmer porpoise, which lived off the coast of what is now California between 5 and 1.5 million years ago. While it probably looked mostly like an ordinary porpoise, its chin grew incredibly long. The chin, properly called a symphysis, was highly sensitive, and researchers think it used it to probe in the mud for food.

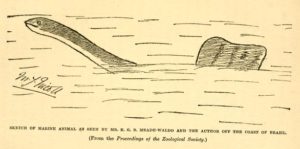

There’s still so much to learn about whales, both living ones and extinct ones. We definitely haven’t identified all the living whales yet. There are reports of strange whales from all over the world, including a baleen whale with two dorsal fins. It was first spotted in 1867 off the coast of Chile by a naturalist, and other sightings have been made since. It’s supposedly 60 feet long, or 18 meters, so you’d think it wouldn’t be all that hard to spot…but there’s a whole lot of ocean out there, and relatively few people on the ocean to look for rare whales.

Whales can live a really long time. In 2007, researchers studying a dead bowhead whale found a piece of harpoon embedded in its skin. It turned out to be a type of harpoon that was made around 1879. Bowheads can probably live more than 200 years, and may even live longer than that.

And, of course, whales are extremely intelligent animals with complex social and emotional lives, the ability to reason and remember, tool use, creative thinking and play, self-awareness, a certain amount of language use, and altruistic behaviors toward members of other species. Whales and dolphins sometimes help human swimmers in distress, dolphins and porpoises sometimes help beached whales, and humpback whales in particular sometimes rescue seals and other animals from orcas. Humans aren’t very good at thinking about intelligence except as it pertains to us, but it seems pretty clear that other apes, whales and their relations, elephants, and probably a great many other animals are a lot more intelligent than we’ve traditionally thought.

One last interesting fact about whales and their relations. Most of them sleep with half their brain at a time. The half that isn’t sleeping takes care of rising to the surface to breathe periodically, so the whale doesn’t drown. That does not sound very restful to me. But sperm whales sleep with their bodies vertical and their heads sticking up out of the water. But they don’t sleep very long, only around ten minutes at a time—and only in the hours before midnight. I’ve had nights like that.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!