Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:30 — 11.8MB)

Thanks to Viki, Erin, Weller, and Stella for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Tasmanian tiger pups found to be extraordinary similar to wolf pups

The thylacine could open its jaws really wide:

A sugar glider, gliding [photo from this page]:

A happy quokka and a happy person:

A swimming platypus:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some marsupial mammals suggested by Erin, Weller, and Stella, and a bonus non-marsupial from Australia suggested by Viki.

Marsupials are mammals that give birth to babies that aren’t fully formed yet, and the babies then finish developing in the mother’s pouch. Not all female marsupials actually have a pouch, although most do. Marsupials are extremely common in Australia, but they’re also found in other places around the world.

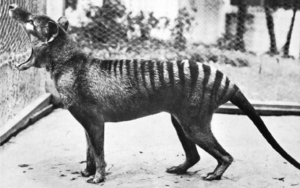

Let’s start with Weller’s suggestion, the Tasmanian tiger. We’ve talked about it before, but not recently. We talked about it in our very first episode, in fact! Despite its name, it isn’t related to the tiger at all. Tigers are placental mammals, and the Tasmanian tiger is a marsupial. It’s also called the thylacine to make things less confusing.

The thylacine was declared extinct after the last known individual died in captivity in 1936, but sightings have continued ever since. It’s not likely that a population is still around these days, but the thylacine is such a great animal that people hold out hope that it has survived and will one day be rediscovered.

It got the name Tasmanian tiger because when European colonizers arrived in Tasmania, they saw a striped animal the size of a big dog, about two feet high at the shoulder, or 61 cm, and over six feet long if you included the long tail, or 1.8 meters. It was yellowish-brown with black stripes on the back half of its body and down its tail, with a doglike head and rounded ears.

The thylacine was a nocturnal marsupial native to mainland Australia and the Australian island of Tasmania, but around 4,000 years ago, climate change caused more and longer droughts in eastern Australia and the thylacine population there went extinct. By 3,000 years ago, all the mainland thylacines had gone extinct, leaving just the Tasmanian population. The Tasmanian thylacines underwent a population crash around the same time that the mainland Australia populations went extinct—but the Tasmanian population had recovered and was actually increasing when Europeans showed up and started shooting them.

The thylacine mostly ate small animals like ducks, water rats, and bandicoots. Its skull was very similar in shape to the wolf, which it wasn’t related to at all, but its muzzle was longer and its jaws were comparatively much weaker. Its jaws could open incredibly wide, which usually indicates an animal that attacks prey much larger than it is, but studies of the thylacine’s jaws and teeth show that they weren’t strong enough for the stresses of attacking large animals.

Next, Stella wanted to learn about the sugar glider, and I was surprised that we haven’t talked about it before. It’s a nocturnal marsupial native to the forests of New Guinea and parts of Australia, with various subspecies kept as exotic pets in some parts of the world. It’s called a glider because of the animal’s ability to glide. It has a flap of skin between its front and back legs, called a patagium, and when it stretches its legs out, the patagia tighten and act as a parachute. This is similar to other gliding animals, like the flying squirrel.

The sugar glider resembles a rodent, but it isn’t. It’s actually a type of possum. It lives in trees and has a partially prehensile tail that helps it climb around more easily, and of course it can glide from tree to tree. It’s an omnivore that eats insects, spiders, and other small animals, along with plant material, mainly sap. It will gnaw little holes in a tree to get at the sap or gum that oozes out. It will also eat fruit, nectar, pollen, and seeds, but most of the time it prefers to hang around flowers and wait for insects to approach. Then it grabs and eats the insect without having to chase it.

The sugar glider is gray with black and white markings, big eyes that allow it to see well in darkness, rounded ears, and a really long, thick, furry tail. It’s a social animal that lives in family groups in small territories. Both males and females help take care of the joeys when they’re out of the mother’s pouch, mainly by helping them stay warm when it’s cold.

Our last marsupial of this episode is Erin’s suggestion, the quokka. It’s about the size of a domestic cat, related to wallabies and kangaroos. It’s shaped roughly like a chonky little wallaby but with a smaller tail and with rounded ears, and it’s grey-brown in color.

The quokka is considered incredibly cute because of the way its muzzle and mouth are shaped, which makes it look like it’s smiling. If you take a picture of a quokka’s face, it looks like it has a happy smile and that, of course, makes the people who look at it happy too.

This has caused some problems, unfortunately. People who want to take selfies with a quokka sometimes forget that they’re wild animals. While quokkas aren’t very aggressive and are curious animals who aren’t usually afraid of people, they can and will bite when frightened. Touching a quokka or giving it food or drink is strictly prohibited, since it’s a protected animal.

The quokka is most active at night. It sleeps during most of the day, usually hidden in a type of prickly plant that helps keep predators from bothering it. It gets most of its water needs from the plants it eats, and while it mostly hops around like a teensy kangaroo, it can also climb trees.

Let’s finish with our non-marsupial animal. Viki wanted to learn about the platypus, which we haven’t really talked about since way back in episode 45. It’s native to Australia and is very weird-looking, so it’s easy to think it’s another marsupial, but the platypus is even weirder than that. It’s not a marsupial and it’s not a placental mammal. Instead, it’s an extremely rare third type of mammal called a monotreme.

There are only two kinds of monotremes alive today, the echidna and the platypus. Monotremes retain a lot of traits that are considered primitive in mammals. Instead of giving birth to live babies, a monotreme mother lays eggs. The eggs have soft, leathery shells, but when they hatch, the babies look like marsupial newborns.

The platypus is sometimes called the duck-billed platypus, because its snout does kind of look like a duck’s bill, but instead of being hard, the snout is soft and rubbery, and it’s packed with electroreceptors that allow the platypus to sense the tiny electrical fields generated by muscle contractions in its prey. I bet that was not what you expected from what looks like a small beaver with a duck bill!

The platypus grows not quite two feet long, or 50 cm, and has short, dense, brown fur. It spends a lot of its time in the water, and has a flattened tail that acts as a rudder when it swims, along with its hind feet. It propels itself through the water with its front feet, which are large and have webbed toes. It lives in eastern Australia along rivers and streams, and digs a short burrow in the riverbank to sleep in. The female digs a deeper burrow before she lays her eggs, and she makes them a nest out of leaves.

Baby platypuses are called puggles, and while the mother doesn’t have a pouch, she keeps her babies warm by tucking them against her tummy with her tail. Monotremes don’t have teats, but they do produce milk from what are called milk patches. The puggles lick the milk up. Until scientists figured out that monotremes have these milk patches, in 1824, they thought monotremes weren’t mammals at all but something more closely related to reptiles.

Monotremes were much more common throughout the world until about 60 to 70 million years ago, when marsupials started outcompeting them. Marsupials don’t spend much time in water, though, because if they did their joeys would drown. The platypus and echidna both survived to the present day because they’re adapted for the water. The platypus mainly navigates in the water using its electrolocation abilities, and eats worms, fish, insects, crustaceans, and anything else it can catch.

It’s easy to think, “Oh, that mammal is so primitive, it must not have evolved much since the common ancestor of mammals, birds, and reptiles was alive 315 million years ago,” but of course that’s not the case. It’s just that the monotremes that survived did just fine with the basic structures they evolved a long time ago, and they’re still going strong today.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!