Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:20 — 16.7MB)

We have merch available again!

Thanks to Eva and Leo for suggesting the tenrec!

Further reading:

Marooned on Mesozoic Madagascar

Introduction to Adalatherium hui

The lowland streaked tenrec:

The hedgehog tenrec rolls up just like an actual hedgehog [photo by Rod Waddington, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]:

Actual hedgehog, not a tenrec:

Lesser hedgehog tenrec REALLY looks like an actual hedgehog [By Wilfried Berns www.Tierdoku.com – Transferred from de.wikipedia to Commons.Orig. source: eigene Fotografie, CC BY-SA 2.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2242515]:

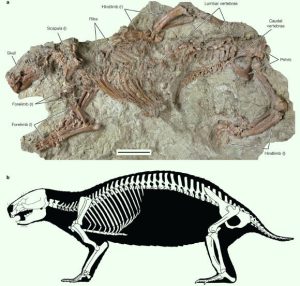

Adalatherium:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about a weird little animal suggested by both Eva and Leo, the tenrec of Madagascar. While we’re at it, we’re going to learn about another little animal found on Madagascar a long time ago that’s one of the weirdest mammals ever discovered.

Before we get started, though, someone sent me a book! If your name is Jennifer or someone named Jennifer mailed this book to me for you, thank you! The book is called The Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw: One Woman’s Fight to Save the World’s Most Beautiful Bird by Bruce Bercott. Thank you so much! I did not know when I started this podcast over six years ago that one of the benefits of doing an animal podcast is sometimes people send you books about animals, which is the best thing in the world. There’s no note so I thought I’d give you a shout-out on the podcast.

As we learned in episode 318, about 88 million years ago, the island of Madagascar broke off from every other landmass in the world, specifically the supercontinent Gondwana. The continent we now call Africa separated from Gondwana even earlier, around 165 million years ago. Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world and even though it’s relatively close to Africa these days, many of its animals and plants are much different from those in Africa and other parts of the world because they’ve been evolving separately for 88 million years.

But at various times in the past, some animals from Africa were able to reach Madagascar. We’re still not completely sure how this happened. Madagascar is 250 miles away from Africa, or 400 kilometers, and these days the prevailing ocean currents push floating debris away from the island. In the past, though, the currents might have been different and some animals could have arrived on floating debris washed out to sea during storms. During times when the ocean levels were overall lower, islands that are underwater now might have been above the surface and allowed animals to travel from island to island until they reached Madagascar.

Sometime between 25 and 40 million years ago, a semiaquatic mammal reached Madagascar in enough numbers that it was able to establish itself on the island. It was related to the ancestors of a semiaquatic mammal called the otter-shrew, even though it’s neither an otter nor a shrew. The otter-shrew lives in parts of Africa and is pretty weird on its own, but we’ll save it for another episode one day. The otter-shrew’s relative did so well in its new home of Madagascar that over the millions of generations since, it developed into dozens of species. We now call these animals tenrecs.

It’s hard to describe the tenrec because the various species are often very different in appearance. There are some things that are basically the same for all species, though. First, the tenrec has a low body temperature, although it varies from species to species and also varies depending on time of year. That’s because some species of tenrec go into torpor when it’s cold, or sometimes full hibernation. During torpor the animal’s body temperature drops even more than usual. The common tenrec hibernates up to nine months out of the year.

Second, the tenrec has a cloaca, which is really unusual in placental mammals. Birds, reptiles, and amphibians have a cloaca, which is a single opening used for excretion and often for giving birth or laying eggs too. Most mammals have separate openings for different uses.

Third, all tenrecs are pretty small with only a little short tail. The biggest is only a little over a foot long at most, or 39 cm, and most are much smaller.

Leo specifically likes the streaked tenrec, so let’s learn about it to give us a better idea of what tenrecs are like in general. There are two species of streaked tenrec and while they live in different parts of Madagascar, they mostly live in tropical rainforests. They’re considered a type of spiny tenrec because they have quills all over like a tiny porcupine or a brightly colored hedgehog. The highland streaked tenrec is black and white, while the lowland streaked tenrec is black and yellow.

The streaked tenrec’s bright coloration gives a warning to potential predators that it is pointy. If a predator doesn’t figure it out, the tenrec will raise its quills and shake them to make a little rattling sound. If that doesn’t stop the predator and it tries to bite the tenrec, the quills can detach and will lodge in the predator’s mouth. That generally gets the point across. (haha, point)

The lowland streaked tenrec also communicates by rubbing its quills together to make ultrasonic sounds. This method of sound production is called stridulation and the streaked tenrec is the only mammal known to make sound this way. It has special muscles at the base of its quills that help it move the quills to make sounds. Stridulation is mostly found in insects, including crickets.

Like most tenrecs, the streaked tenrec has a long, thin snout and short legs. It spends a lot of its time digging for earthworms and other invertebrates, and it also eats fruit. It lives in family groups that sleep in shallow burrows. Also, it’s super cute. Just don’t lick it.

Another tenrec with spines is the hedgehog tenrec, which looks and acts incredibly like a hedgehog even though it’s not related. That’s yet another example of convergent evolution. The lesser hedgehog tenrec and the greater hedgehog tenrec, which by the way belong to different genera, are nocturnal animals that live in open forests, savannas, and people’s gardens in Madagascar. During the day it stays hidden in dead leaves or brush, or in a hollow of a tree trunk, and at night it comes out to find insects and other small animals to eat. If it feels threatened, it will roll up into a ball to protect its belly while turning itself into a very pointy mouthful. Its spines don’t come loose the way the streaked tenrec’s do, but they’re sharp. Sometimes a hedgehog tenrec will back up quickly toward a potential predator. If it backs into the predator’s nose, suddenly the predator discovers it’s not all that hungry and its nose hurts and it’s just going to leave.

Many species of tenrec resemble shrews. They’re smaller than a mouse, which they otherwise resemble except that they have a long nose and short tail, and they don’t have quills. Most tenrecs have 6 or 8 babies at a time, but some have more. The common tenrec can have up to 32 babies at a time. It has 29 teats! That’s the most teats known in any mammal.

All this is amazing, but while I was researching the tenrec I learned about an even weirder animal that lived on Madagascar at the end of the Cretaceous. That animal wasn’t a dinosaur, though. It was a mammal.

It was discovered by a team of paleontologists in 1999, but they didn’t actually know they’d discovered it. They thought the piece of rock only contained a small crocodyliform. When preparation of the specimen started in 2002, the scientist working on it received an incredible surprise. In addition to fossil remains of both an adult and a baby crocodyliform, there was an almost complete, articulated skeleton of a weird mammal. All three animals may have been buried suddenly by debris carried by a flash flood, which is why they’re so well preserved.

Most mammals that lived alongside dinosaurs were really small, maybe the size of rats at most, but Adalatherium was about the size of a cat. It may have actually grown larger than a cat, because the only specimen we have is an individual that wasn’t fully grown. It was built sort of like a little badger, with a broad body, short legs, short tail, and short snout.

Adalatherium is a member of a group of mammals called Gondwanatheria, which arose in the southern hemisphere around the time that the supercontinent Gondwana was breaking apart. We only have a few fossils of these animals so paleontologists still don’t know how they’re related, but Adalatherium is a big deal because it’s so detailed and almost the whole skeleton is preserved. Paleontologists have known for a long time that these Gondwanatheria were probably not related to modern mammals, but until Adalatherium was discovered no one realized just how weird these animals were.

If you could go back in time to look at Adalatherium when it was alive, you might not think it was all that weird. Also, you’d be a little distracted because dinosaurs would probably be trying to eat you. Most of the weird details probably weren’t visible, but they’re very obvious to scientists studying the fossilized bones. For instance, Adalatherium had a lot of vertebrae in its backbone, more than other mammals—at least 30 total thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Humans have 17 total and cats have 20, to give you a comparison with modern mammals.

Adalatherium also had weird legs, with its front legs not really seeming to match its rear legs. Its front legs are longer with a strong shoulder, while its rear legs are short and bowed. Paleontologists think it might have been a burrowing animal, which would explain why its rear legs are strangely shaped compared to its front legs, but it could probably run pretty fast too. It also had unusual double grooves on its anklebones.

Another weird thing about Adalatherium was its skull. The parts of the skull that made up the nasal cavity had lots of little holes in it, called foramina, for nerves and blood vessels to pass through. This isn’t unusual in itself, but Adalatherium had more foramina than any other mammal ever examined, living or extinct. One of the foramen was on top of the snout and doesn’t match up with anything seen in any other mammal. Adalatherium probably had a whole lot of very sensitive whiskers, but for all we know, all the foramina were for some other sensory structure, one that was unlike any found in modern mammals.

Adalatherium lived at the end of the Cretaceous, and it’s possible it went extinct along with the non-avian dinosaurs. Gondwanatheria in general all went extinct by around 43 million years ago and as far as we know, no living descendants are still around. But we know very little about these interesting mammals. Hopefully more fossils of Gondwanatheria in general, and Adalatherium in particular, will turn up soon so we can learn more.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!