Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:25 — 13.7MB)

This week let’s learn about some animals that were discovered by science, then not seen again and presumed extinct…until they turned up again, safe and sound!

Further reading:

A nose-horned dragon lizard lost to science for over 100 years has been found

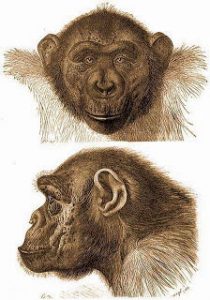

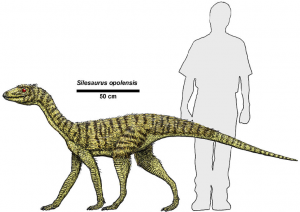

Modigliani’s nose-horned lizard has a nose horn, that’s for sure:

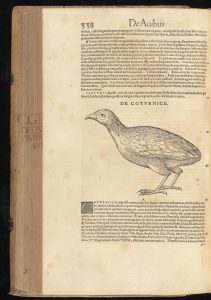

Before the little guy above was rediscovered, we basically just had this painting and an old museum specimen:

The deepwater trout:

The dinosaur ant:

The dinosaur ant statue of Poochera:

The false killer whale bite bite bite bite bite:

Some false killer whales:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s learn about some animals that were discovered by scientists but then lost and assumed extinct, until they were found again many years later. There’s a lot of them and they’re good to think about when we feel down about how many species really are extinct.

We’ll start with a brand new announcement about a reptile called Modigliani’s nose-horned lizard, named after an Italian explorer named Elio Modigliani. He donated a specimen of the lizard to a natural history museum when he got home from exploring Indonesia. That was in 1891, and in 1933 scientists finally described it formally as Harpesaurus modiglianii.

The lizard was especially interesting because it had a horn on its nose that pointed forward and slightly up, and it had spines along its back. It looked like a tiny dragon.

But no one saw another one, not in Indonesia, not anywhere. Researchers knew it had lived where Modigliani said it did because a group of people from Indonesia called the Bataks knew about the lizard. It was part of their mythology and they carved pictures of it. But they didn’t have any, live or dead. Researchers thought it must have gone extinct.

Until 2018. In June 2018, a wildlife biologist named Chairunas Adha Putra was surveying birds in Indonesia, specifically in North Sumatra, when he found a dead lizard. Putra isn’t a lizard expert but he thought it might interest a herpetologist colleague named Thasun Amarasinghe, so he called him. Amarasinghe said oh yeah, that does sound interesting, do you mind sending it to me so I can take a look?

And that’s history, because once he saw it, Amarasinghe knew exactly what the lizard was.

Amarasinghe immediately called Putra, who was still out surveying birds. Could Putra please go back to where he’d found the dead lizard and see if he could find another one, preferably alive? It was really important.

Putra returned obligingly and searched for another lizard. It took him five days, but finally he found one asleep on a branch. He caught it and took pictures, measured it, and observed it before releasing it a few hours later. Hurray for scientists who go that extra mile to help scientists in other fields!

Modigliani’s nose-horned lizard is bright green with a yellow-green belly and spines, plus some mottled orange markings. At least, that’s what it looks like most of the time. It can change colors just like a chameleon. If it’s feeling stressed, it turns a darker gray-green and its spines and belly turn orangey. But it can change its color to match its environment too.

It’s related to a group of lizards called dragon lizards, which includes the bearded dragon that’s often kept as a pet. There are a lot of dragon lizards, and 30 of them have never been seen since they were first described.

Unfortunately, deforestation and habitat loss throughout North Sumatra and other parts of Indonesia threaten many animals, but the Modigliani’s nose-horned lizard was found just outside of a protected area. Hopefully it will stay safely in the protected area while scientists and conservationists study it and work out the best way to keep it safe.

A fish called the deepwater trout, also known as the black kokanee or kunimasu salmon, used to live in a Japanese lake called Lake Tazawa, and that was the only place in the world where it lived. It’s related to the sockeye salmon but it’s much smaller and less flashy. It grows to about a foot long, or 30 cm, and is black and gray in color as an adult, silvery with black markings as a young fish.

In the 1930s, plans to build a hydroelectric power plant on the lake alarmed scientists. The plan was to divert water from the River Tama to work the power station, after which the water would run into the lake. The problem is that the River Tama was acidic with agricultural runoff and water from acidic hot springs in the mountains. The scientists worried that if they didn’t do something to help the fish, soon it would be too late.

In 1935 they moved as many of the fish’s eggs as they could find to other lakes in hopes that the species wouldn’t go extinct. In 1940 the plant was completed, and as expected, the lake’s water became too acidic for the deepwater trout to survive. In fact, it became too acidic for anything to survive. Soon almost everything living in the lake was dead. Within a decade the lake was so acidic that local farmers couldn’t even use it for irrigation, because it just killed any plants it touched. Lake Tazawa is still a mostly dead lake despite several decades of work to lessen its acidity by adding lime to the water.

So, the deepwater trout went extinct in Lake Tazawa along with many other species, and to the scientists’ dismay, they found no sign that the eggs they’d moved to other lakes had survived. The deepwater trout was listed as extinct.

But in 2010, a team of scientists took a closer look at Lake Saiko. It’s one of the lakes where the deepwater trout’s eggs were transferred, and it’s a large, deep lake near Mount Fuji that’s popular with tourists.

The team found nine specimens of deepwater trout. Further study reveals that the population of fish is healthy and numerous enough to survive, as long as it’s left alone. Fortunately, Lake Saiko is inside a national park where the fish can be protected.

Next, let’s look at a species of ant called the dinosaur ant. It was collected by an amateur entomologist named Amy Crocker in 1931 in western Australia. Crocker wasn’t sure what kind of ant she had collected, so she gave the specimens to an entomologist named John Clark. Clark realized the ant was a new species, one that was so different from other ants that he placed it in its own genus.

The dinosaur ant is yellowish in color and workers have a retractable stinger that can inflict painful stings. It has large black eyes that help it navigate at night, since workers are nocturnal. It lives in old-growth woodlands in only a few places in Australia, as far as researchers can tell, and it prefers cool weather. Its colonies are very small, usually less than a hundred ants per nest. Queen ants have vestigial wings while males have fully developed wings, and instead of a nuptial flight that we talked about in episode 175 last month, young queens leave the nest where they’re hatched by just walking away from it instead of flying. Males fly away, and researchers think that once the queens have traveled a certain distance from their birth colony, they release pheromones that attract males. If a queen with an established colony dies, she may be replaced with one of her daughters or the colony may adopt a young queen from outside the colony. Sometimes a queen will go out foraging for her food, instead of being restricted to the nest and fed by workers, as in other ant species.

The dinosaur ant is called that because many of its features are extremely primitive compared to other ants. It most closely resembles the ant genus Prionomyrmex, which went extinct around 29 million years ago. Once researchers realized just how unusual the dinosaur ant was, and how important it might be to our understanding of how ants evolved, they went to collect more specimens to study. But…they couldn’t find any.

For 46 years, entomologists combed western Australia searching for the dinosaur ant, and everyone worried it had gone extinct. It wasn’t until 1977 that a team found it—and not where they expected it to be. Instead of western Australia, the team was searching in South Australia. They found the ant near a tiny town called Poochera, population 34 as of 2019, and the town is now famous among ant enthusiasts who travel there to study the dinosaur ant. There’s a statue of an ant in the town and everything.

The dinosaur ant is now considered to be the most well-studied ant in the world. It’s also still considered critically endangered due to habitat loss and climate change, but it’s easy to keep in captivity and many entomologists do.

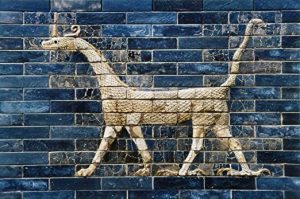

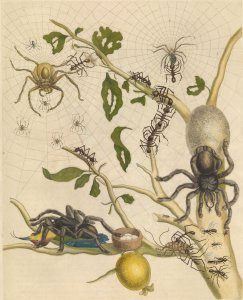

Let’s finish with a mammal, and the situation here is a little different. In 1846 a British paleontologist published a book about British fossils, and one of the entries was a description of a dolphin. The description was based on a partially fossilized skull discovered three years before and dated to 126,000 years ago. It was referred to as the false killer whale because its skull resembled that of a modern orca. Scientists thought it was the ancestor of the orca and that it was extinct.

Uh, well, maybe not, because in 1861, a dead but very recently alive one washed up on the coast of Denmark.

The false killer whale is dark gray and grows up to 20 feet long, or 6 meters. It navigates and finds prey using echolocation and mostly eats squid and fish, including sharks. It’s not that closely related to the orca and actually looks more like a pilot whale. It lives in warm and tropical oceans and some research suggests it may migrate to different feeding spots throughout the year. It often travels in large groups of a hundred individuals. That’s as many dolphins as there are ants in dinosaur ant colonies. Part of the year it spends in shallow water, the rest of the year in deeper water, only coming closer to shore to feed.

Researchers are only just starting to learn more than the basics about the false killer whale, and what they’re learning is surprising. It will share food with its family and friends, and will sometimes offer fish to people who are in the water. It sometimes forms mixed-species groups with other species of dolphin, sometimes hybridizes with other closely-related species of dolphin, and will protect other species of dolphin from predators. It’s especially friendly with the bottlenose dolphin. So basically, this is a pretty nice animal to have around if you’re a dolphin, or if you’re a swimming human who would like a free fish. So it’s a good thing that it didn’t go extinct 126,000 years ago.

This is what the false killer whale sounds like:

[false killer whale sounds]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!