Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:59 — 14.4MB)

It’s another spooky episode (three out of five bats on this year’s spookiness scale), with suggestions from Will and Pranav!

Further reading:

Further watching:

The Harlan Ford Footage (Honey Island Swamp Monster)

A crab-eating macaque:

A plaster cast purportedly from the Honey Island Swamp Monster’s footprints [photo from article linked above]:

Alligator tracks in the mud [photo from this site]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week as monster month continues, we’ll learn about three more strange bipedal monsters suggested by Will and Pranav. This is another episode that I’ll give three out of five bats for spookiness. We’ve definitely got some spooky monsters this year (also you may be sensing a theme).

We’ll start with Will’s suggestion, the yara-ma-yha-who. We talked about it once before back in episode 219, but it’s such a strange monster that it definitely deserves more attention.

According to a 1932 book called Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, the yara-ma-yha-who is a little red goblin creature that stands about four feet tall, or 1.2 meters. It’s skinny all over except for its head and belly, and its mouth is especially big, like a frog’s mouth. It doesn’t have any teeth, but it can open its jaws incredibly wide like a snake, which allows it to swallow its food whole. And what is its food? People!

The yara-ma-yha-who was supposed to live in trees, especially the wild fig tree that has thick branches. In the summer when someone would stop under the tree for shade, or in the winter when it was rainy and someone would stop for shelter, the yara-ma-yha-who would drop down and grab the person.

The ends of the yara-ma-yha-who’s fingers were said to be cup-shaped suckers, and when the suckers fastened onto a person’s arm, they were able to suck blood right through the person’s skin. After the person became weak from blood loss and fainted, the yara-ma-yha-who was able to swallow them whole.

After that, the yara-ma-yha-who would drink a lot of water and fall asleep, and when it woke up it would vomit up its meal. If the person was still alive, they were supposed to lie still and pretend to be dead even while the yara-ma-yha-who poked at them to see if they responded. If the person moved, the yara-ma-yha-who would swallow them again and the whole thing would start over. But every time a person was swallowed by the little red goblin, when they were vomited up again they were shorter and redder, until after three or four times if they couldn’t get away, the person was transformed into another yara-ma-yha-who.

Some cryptozoologists speculate that the yara-ma-yha-who may be based on the tarsier, which is the subject of episode 219 and why we talked about this particular monster in that episode. The tarsier has never lived in Australia, although it does live in relatively nearby islands. Most tarsier species have toe pads that help them cling to branches, but so do many frogs that do live in Australia. It’s much more likely that the legend of the yara-ma-yha-who was inspired by frogs, snakes, monitor lizards, and other Australian animals. More importantly, the monster was used as a cautionary tale to warn children not to go off by themselves into the bush.

Unfortunately, the only information about the yara-ma-yha-who comes from this 1932 book. We don’t know which Aboriginal peoples this story was collected from, and we don’t know how much it was changed in translation to English. It’s still a fun story, though.

Next, we’ll talk about Pranav’s suggestions. Last week we talked about the monkey-man of New Delhi, and one of the monsters we’ll cover today is also a monkey-man from Asia, this time from Singapore. It’s the Bukit Timah Monkey-Man, said to mainly live in the Bukit Timah rainforest nature reserve but occasionally seen in the city surrounding the nature reserve.

The Bukit Timah Monkey-Man is supposed to look like a monkey the size of a human. It walks like a human on two legs and otherwise looks like a person, but is covered in gray hair and has a monkey-like face. It’s only ever seen at night and although people are scared when they see it, the monster has never attacked anyone and doesn’t seem to be interested in people at all. The oldest report possibly dates back to 1805, or to the 1940s according to other accounts, but sightings are rare.

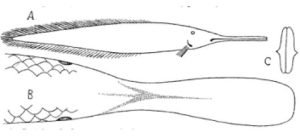

One very common monkey that lives in Bukit Timah is the crab-eating macaque, also called the long-tailed macaque and I bet you can guess why. Its tail is longer than its body, although its arms and legs are shorter than in most monkeys. It mostly lives on the ground and eats pretty much anything, although most of its diet is fruit and other plant materials. It does sometimes eat crabs, and is good at swimming and diving to find them, but it also eats bird eggs and nestlings, lizards, frogs, insects, and other small animals. It even has a cheek pouch where it can store extra food to eat later.

Like the rhesus macaque we talked about last week, the crab-eating macaque is pretty small, with a big male weighing about 20 lbs, or 9 kg, at most. That’s about the size of a small dog. The fur on its back and head is a light golden brown, and its face, arms and legs, and underparts are gray with white markings. Its tail is usually darker brown. In other words, in the dark it might look like it’s pale gray all over but its tail is harder to see, and the monkey-man isn’t reported to have a tail.

The crab-eating macaque is common in the city of Bukit Timah, and in fact it’s common in a lot of cities and is even an invasive species in some parts of the world. People in Bukit Timah are used to seeing this particular type of monkey, but it’s so small that no one could mistake it for a human-sized monster. Then again, most of the stories about the monkey-man are friend-of-a-friend stories, often told by children to scare each other. It’s very likely that the Bukit Timah monkey-man is just an urban legend.

Our last monster this week is another suggestion by Pranav, the Honey Island Swamp monster. This one is from the United States, specifically the Honey Island Swamp in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana.

In 1974, a couple of hunters claimed they found strange footprints in the swamp, and had seen the monster itself back in 1963. They said it stood seven feet tall, or over 2 meters, and was covered with long gray hair. Its eyes were a brilliant amber in color. The monster was on all fours at first, but when it heard the men talking it stood up to look at them, then ran away. Heavy rain later that day washed its tracks away.

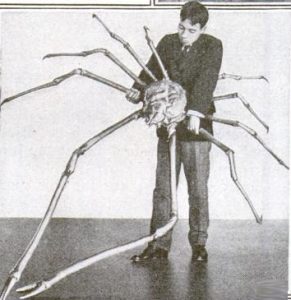

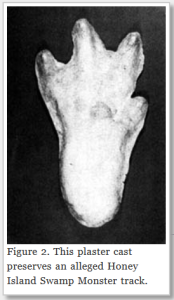

When the men saw the same tracks in 1974, they used plaster to make copies of the footprints. But the footprints don’t look like plaster casts of other bigfoot-type tracks, which resemble giant human footprints. The swamp monster appears to have four toes that are spread widely apart, with one sticking out to the side like a thumb, and show the impression of webbing in between. It’s also not that big of a foot, not quite 10 inches long, or 25 cm.

Both the hunters were air traffic controllers, which is a job that requires people to make decisions carefully and remain calm in stressful situations, in order to keep airplanes from crashing into each other. These were the sort of people you’d trust if they told you they’d seen something really weird in the swamp. The two men were even interviewed for an episode of the TV show “In Search Of” that aired in 1978, which popularized the Honey Island Swamp monster outside of the local area. Both men continued to search for the monster, reporting that they’d caught at least one more glimpse of it and had even shot at it without apparently hitting it.

One of the men, Harlan Ford, died in 1980. He had taken up wildlife photography after his retirement and when his granddaughter was going through his belongings, she found some Super 8 film footage that showed something very peculiar. It was a brief video of the swamp, but if you look closely, a shadowy human-sized figure crosses behind trees from right to left, visible for maybe half a second. I put a link in the show notes if you want to look at the footage yourself. It took me two watches before I noticed the figure and to me it looks like the shadow of a human walking normally, but it’s so grainy it’s hard to tell.

It’s possible that the two men decided to have fun with a harmless prank about a monster in the swamp, but so many people took them seriously that it kind of got out of hand. Then again, maybe they did genuinely see something unusual. That doesn’t mean it was an actual monster, though. Black bears do live in the swamp, and my personal theory is that bears are responsible for a whole lot of bigfoot sightings.

The American alligator is also common in the area. The gator’s front feet have five toes, but the hind feet only have four. The toes are webbed to help the gator swim more easily, and the front foot’s pinkie toe usually sticks out to the side. Sometimes the first two toes of the front foot are held close enough together that they look like one big toe. Usually an alligator drags its tail as it walks, but it also has a gait called the high walk where its tail is completely off the ground. The plaster tracks found by the two hunters in 1974 look suspiciously like a really big alligator print, probably twice the size of an ordinary adult gator.

More importantly, people who have lived in the Honey Island swamp their entire lives, fishing and hunting and running boat tours, don’t report ever seeing an animal they don’t recognize. Maybe there is an incredibly rare monster that lives in the swamps and walks bipedally at least part of the time, but more likely the Honey Island Swamp Monster is a tall tale.

There are a lot of reasons why people tell stories about swamp monsters or monkey-men or murderous red goblins. It’s a good way to stop little kids from wandering around in dangerous places, and it’s fun to scare yourself and others with a story when you know you’re actually safe. There are plenty of dangerous animals in the world, many of which are completely unknown to science. I just don’t think these three are ones you need to worry about.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!