Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:52 — 16.4MB)

This week we’re staying at home and looking around our own yards and gardens to learn about some of the little critters we see every day but maybe never pay attention to. Thanks to Richard E. for the topic suggestion, and thanks also to John V. and Richard J. for other animal suggestions I used in the episode!

The common or garden snail:

A couple of robins:

A brown-eared bulbul nomming petals:

An Eastern hognose snake. srsly, no one believes ur dead snek:

The hognose in happier times:

An Australian water dragon. Stripey!!

The edible dormouse. I think you mean the ADORABLE dormouse:

The eastern chipmunk:

A guppy with normal eyes:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

I’m out of the country this week, visiting Paris, France and undoubtedly eating my weight in pastries and cheese as you listen to this. Since I’m away from home, though, I’m probably feeling a little homesick. So this week’s episode is all about the ordinary-seeming little animals found in gardens and yards, a suggestion from Richard E. This is also a perfect opportunity to feature some listener-suggested animals that aren’t really complex enough for a full episode but are still really interesting.

But I’m not going to just look at the animals in my yard. Depending on where you live, hopefully I’ll touch on one or two animals you might be able to see for yourself just by going outside and looking around.

It sounds corny, but no matter how boring you think the nearest patch of greenery is, if you look closely enough you’ll see a world of activity. The other day I was sitting on a bench outside the library, enjoying a breeze and the shade of an oak tree, and because I am sort of disgusting and was wearing flip-flops, I was picking at one of my toenails that was partly broken. I pulled the broken part off and flipped it into the grass nearby. A few minutes later I noticed that a couple of ants had found that piece of toenail and were working hard to wrestle it over the grass and twigs and presumably back to their home. Why? Why did they want my toenail? It’s just a piece of keratin, and while keratin is a type of protein, it’s not digestible by most animals.

I looked it up, and guess what. I am not the first person to notice this. No one’s sure why ants take toenail and fingernail clippings, either. They’re not interested in hair, just nails. Hair and nails have different properties so it’s possible the ants are able to digest the keratin in nails but not the keratin in hair.

That was probably not the best story to start with. Try to forget that picture of me and remember that I’m sipping wine at a sidewalk café in Paris right now, or touring the Louvre.

Let’s move on to a small invertebrate that is sometimes eaten as a delicacy in France and other parts of Europe, the common or garden snail. That’s Cornu aspersum, which is native to the Mediterranean and western Europe, but which has been introduced in other parts of the world. It’s pretty big for a snail, with a shell almost 2 inches across, or 5 cm. The shell varies in color and pattern, but it’s usually brown with yellow markings.

The shells almost always coil to the right, or clockwise, but the occasional rare snail will have a left-coiling shell. Researchers have found that left-coiling shells are due to a genetic mutation and only occur about once in a million snails. A famous lefty snail was called Jeremy, who died in October 2017 at the ripe old age of two years. Since snails are hermaphrodites who both fertilize other snails’ eggs and lay their own, a boy name seems like a random choice. Jeremy was discovered by a retired scientist in his London garden, who gave the snail to the University of Nottingham for study. After a public appeal, two other left-handed snails were found by the public, but while the three snails all laid eggs, all the babies had clockwise shells.

The garden snail mostly eats plants, but will sometimes scavenge on small dead animals like drowned worms and squished slugs. When it’s threatened, it can pull itself all the way into its shell, and if it’s too dry out, it will pull itself into its shell and secrete a thin layer of mucus, which dries out to form a seal.

Snails raised to be eaten are kept in special cages, traditionally made from wine-grape vines. I am probably not going to eat any snails while I’m in France, but you never know. I will let you know if I do.

One animal Richard E. suggested as a topic is the robin, specifically the difference between the American robin and European robin. That’s a good one for this episode, because in both North America and Britain, the robin is a really common bird—so common that most people barely pay any attention to it.

The American robin is a type of thrush. It lives year-round in most of the United States and part of Mexico, spends summers in much of Canada, and winters in parts of Mexico. It’s big for a songbird, around 10 inches long, or 25 cm. It’s dark gray on its back, with a rusty red breast, white undertail coverts, and a long yellow bill. It also has white markings around its eyes. Young birds are speckled. It mostly eats insects, worms, and berries. If you see a bird on the ground, running quickly and then stopping, it’s probably a robin. Mostly the robin hunts bugs by sight, but it has good hearing and can actually hear worms moving around underground. You can sometimes see a robin with its head cocked, listening for a worm, before pouncing and pulling it out of the ground, just like in a cartoon.

American robin eggs are a light teal blue, so common and well-known that robin’s-egg-blue is a typical description of that particular color. In the spring after eggs hatch, the mother robin will carry the eggshells away from the nest to drop them, so predators won’t see the shells and know there’s a nest nearby. That’s why you’ll sometimes see half a robin eggshell on the sidewalk. It doesn’t mean something bad happened to the baby, just that the mother bird is doing her job. Both parents feed the chicks, and the parents also carry off the babies’ droppings to scatter them away from the nest.

This is what an American robin’s song sounds like. If you live in North America, you’ve probably heard this song a million times without noticing it.

[robin song]

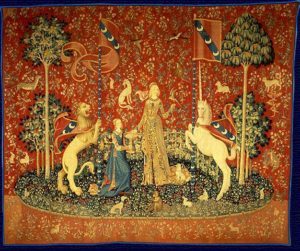

The American robin was named after the European robin, also called the robin redbreast, but while the European robin does have a rusty red breast, it doesn’t look much like the American robin. The European robin is much smaller, only around 5 inches long, or 13 cm, with a brown back, streaked gray or buff belly, and orange face and breast. It has a short black bill and round black eyes. It eats insects, worms, berries, and seeds. The eggs are pale brown with reddish speckles.

It lives throughout much of Eurasia, but robins in Britain tend to be fairly tame, probably because they were traditionally considered beneficial in Britain and Ireland, so farmers and gardeners wouldn’t hurt them. In other parts of Europe they were hunted and are much more shy. European robins are also common on Christmas cards in Britain and Ireland, possibly because in the olden days, postmen used to wear red jackets. They started to be called robins as a result, and since postmen bring Christmas cards, the bird robin became linked with card delivery and finally just ended up on Christmas cards. Plus, their orange markings are cheerful in winter. And, of course, in the traditional story Babes in the Wood, which is often associated with Christmas pantomimes, robins cover the children’s dead bodies with leaves. Because nothing says Christmas spirit like a story about dead children.

This is what the European robin sounds like. If you live in Britain or parts of Europe, you’ve probably heard this song a million times without noticing it.

[other robin song]

Another common bird in gardens, this one from Japan and other parts of Asia, is the brown-eared bulbul. It’s about the size of the American robin, around 11 inches long, or 28 cm, including its long tail. It’s gray or gray-brown all over, with a speckled breast and belly, a sharp black bill, and a dark brown spot on the sides of its head that gives it its name. It mostly eats plants, including fruit, seeds, flowers, and even leaves. I have a picture in the show notes of one chowing down on a flower, just swallowing petals like it’s in a video game and petals give it a power-up. It likes nectar too, and in spring and summer especially will look like it has a yellow head or yellow markings because of all the pollen on its feathers. It helps pollinate plants as a result. It also sometimes eats insects. It gathers in large flocks at times and many farmers consider it a pest, especially fruit farmers.

It has a loud song and call that many people dislike. I’ll let you decide, if you’re not already familiar with it. I kind of like it, to be honest. This is what a brown-eared bulbul sounds like:

[brown-eared bulbul call]

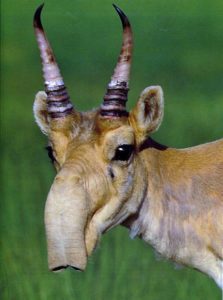

Listener John V. recently suggested the Eastern Hognose snake for an episode, and tickled me because he referred to it as the “dramatic hognose snake.” The hognose is a common snake in many parts of North America, and can grow almost four feet long, or 116 cm, although about half that length is much more average. Its snout turns up like a little snub nose. It varies in color and pattern, and some snakes are black or gray, some orange, brown, even greenish. Some snakes have no pattern, some snakes have various colored blotches or even a checkered pattern. The belly is usually yellowish but is sometimes gray or almost white. It has a big head that makes some people believe it’s venomous, but it’s actually harmless to humans and most animals.

The only animals that really need to worry about the Eastern hognose are amphibians, like toads and frogs. As it happens, the hognose does have mild venom, but it’s only effective on amphibians. It especially likes to eat toads, and while some toads are toxic, the hognose snake is resistant to toad toxins. A toad will frequently puff itself up to make it appear larger and make it hard for a snake to eat, but the Eastern hognose has a solution for that too. It has big teeth at the rear of its upper jaws, like fangs in the back of its mouth. It uses those teeth to puncture puffed-up toads so they deflate.

But the most memorable thing about the Eastern hognose, and the thing that earns it the drama snake award, is what it does when it feels threatened. Phase one of the dramatics is aggression. The snake will flatten its neck to look more threatening, raise its head like a cobra, and hiss and strike—but without biting. It’s just trying to scare you away. If that doesn’t work, the snake puts phase two into effect. It will flop down and roll onto its back, its tongue hanging out, and emit a foul musky smell from its cloaca, and play dead. If you call its bluff and roll drama queen snake onto its belly, it will turn onto its back again. It is really insistent that it is dead.

A common reptile visitor to yards in Australia is the water dragon. Of course Australia would have a little dragon running around in suburban neighborhoods. Males can grow up to three feet long, or a little over a meter, with females smaller, but those lengths include a tail that’s almost twice the length of the body. Males are more brightly patterned than females. It’s a long-leggedy lizard with a spiky crest along its head and spine. It’s generally a pale greeny-grey with dark stripes, especially on the tail and legs, or gray with white stripes. Depending on the species and individual, it may also have a colorful blotch on the throat, usually white or yellow, but sometimes orange or red.

It’s a fast runner and can even run on its hind legs if it really needs to hurry. It climbs trees well, but it especially likes water and is semi-aquatic. Its long tail helps it swim. It likes to bask on branches overhanging the water, and if something threatens it, it drops into the water, where it hides. It can stay underwater without needing to take another breath for over half an hour. It eats small animals like frogs and worms, crustaceans and mollusks, insects, fruit, and plants.

In areas where it gets cold in winter, such as Sydney, the water dragon will dig a burrow if it doesn’t already have one, close the entrance off with dirt, and hibernate until spring, when it emerges and starts searching for a mate. Males sometimes fight each other, biting and scratching. Once the weather is warm, the female lays 6 to 18 eggs in a hole she digs in sandy soil.

Water dragons will visit yards if there’s cover and a water source nearby, whether it’s a creek or just a dog’s water bowl. Don’t try to pet one, though. Dragons bite.

Now let’s look at a couple of common rodents. The edible dormouse lives throughout much of western Europe and is big, about the size of a squirrel, which it also roughly resembles. It’s grey or grey-brown with paler underparts. In autumn when it’s preparing for hibernation it gets very fat, which is why it’s also called the fat dormouse. The name edible dormouse comes from the Romans, who used to farm them in captivity and eat them as a delicacy. In some parts of Europe, especially Slovenia, wild edible dormice are still trapped and eaten.

The edible dormouse lives in dense forests, caves, and people’s attics, where it can be a real pest. It eats plants, especially fruit and nuts, but will eat bark and leaves, and sometimes bird eggs and insects. It especially likes beech tree seeds. It’s mostly nocturnal. Unlike most rodents, it doesn’t always breed every year.

If a predator grabs the edible dormouse’s tail, the skin and fur will slide off, allowing the dormouse to escape. The exposed tail vertebrae later break off and the wound heals up, making the tail shorter. That is kind of horrifying.

Chipmunks are rodents common throughout North America, although the Siberian chipmunk lives in Asia. The Eastern chipmunk is the one I’m going to talk about today, primarily because I got audio of one calling this morning on my way to work. I spilled coffee all over myself to get the audio, so I definitely want to share it.

The chipmunk is larger than a mouse but smaller than a squirrel. It has reddish-brown fur with stripes down its sides, a white band in between two thinner black bands. It prefers woodlands with lots of brush and rocks to hide in, but it lives in parks, yards, and definitely all over the college campus where I work. It climbs trees well but mostly it stays on the ground. It digs complex burrows with tunnels that can be more than 11 feet long, or 3.5 meters. It even digs a special latrine burrow to keep droppings out of the rest of the burrow system, and will throw nut shells and other trash into the latrine too. When it’s digging a new tunnel or burrow, it carries the dirt it’s dug away from the tunnel entrance in its cheek pouches, so predators won’t notice newly dug soil and come to take a look.

The chipmunk is omnivorous, and eats everything from bird eggs, worms, snails, and insects to seeds, nuts, and mushrooms. It even eats small animals like baby mice and nestling birds. It carries food in its cheek pouches to store for the winter, and helps disperse some plants as a result. It doesn’t hibernate, but in winter it spends most of its time sleeping, which is pretty much what I like to do in winter too.

THIS is what an Eastern chipmunk sounds like! A cup of coffee died to bring you this audio:

[chipmunk sound]

Our final animal isn’t something you’d typically find in your yard or garden—but you might find it in your house, if you have a freshwater aquarium: the guppy. A different Richard suggested this animal, specifically my brother Richard. He texted me a while back about Poecilia reticulata, a “common aquarium fish that can turn its little eyes black.” Then we texted back and forth about how that would be a really neat superpower, and how we would apply it in our lives if we could turn our eyes black.

The guppy is a tropical fish native to parts of South America, although it’s been introduced into the wild in other parts of the world and is an invasive species in many places. In the wild it eats algae, insect larvae, and various tiny animals. It’s usually between one and two inches long, or 3 to 6 cm, with females being larger. Females are gray or silvery in color, while males are gray with spots of bright color. Aquarium enthusiasts breed different strains of guppy that may have bright colors and striking patterns.

So does the guppy turn its eyes black? Yes, it really does. Most of the time guppies have silver eyes, but some species can change their eye color in only seconds. In the wild, guppies that live in dangerous areas with many predators tend to group together and cooperate. But guppies that live in safer areas tend to be loners and more aggressive toward each other. When a guppy is angry at another guppy, it turns its eyes black to indicate that it’s willing to fight. Other guppies may back off at that point, or if the other guppy is bigger, it may attack. Researchers don’t know yet how guppies change their eye color.

Until next week, when I’m home from Paris and hopefully caught up on my sleep, remember to look around at the strange little animals in your own backyard. But watch out if their eyes turn black.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!