Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:02 — 21.4MB)

Subscribe: | More

Happy Halloween, everyone! This week’s episode is about a spooky occurrence in 1855, where people in Devon woke to find small hoofprints all over the place, even on roofs. Join us in an attempt to figure out just what animal might have made the devil’s footprints!

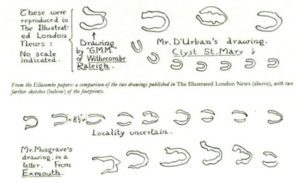

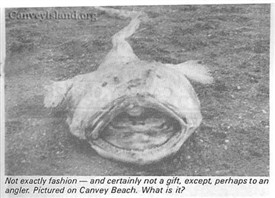

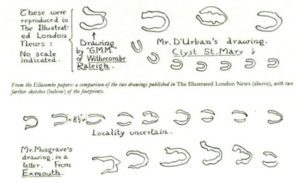

The footprints as drawn by the Rev. Ellacombe from newspaper accounts:

The h*ckin adorable wood mouse:

Link to lots of pictures of jumping wood mice omg

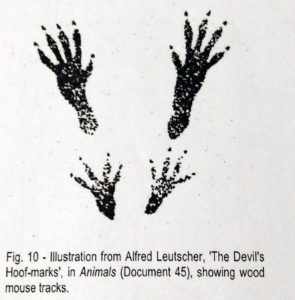

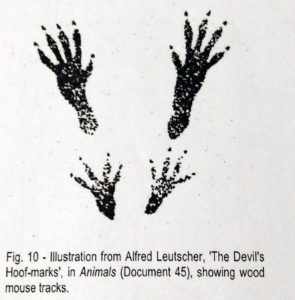

Wood mouse prints from jumping, from Leutscher via Dash (see further reading, below):

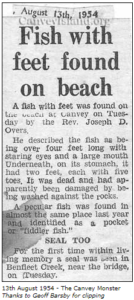

Mystery print from 2009:

Further reading:

The Devil’s Hoofmarks: Source Material on the Great Devon Mystery of 1855 edited by Mike Dash

HALLOWEEN BONUS AW YISS! I’ve unlocked the following Patreon bonus episodes so everyone can listen. You should be able to open them in your browser without needing a Patreon login:

Animals That Glow

The Beast of Busco

Weird Teeth

Carnivorous Plants

Also thank you for buying a lot of copies of my book Skytown:

Amazon USA

Amazon UK

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast Halloween episode for 2017. I’m your host, Kate Shaw. This is the best time of the year if you like candy, ghost stories, monsters, wearing spooky costumes, and buying all the bat decorations in Target. I have so many bat decorations. I’ve stopped taking them down after Halloween and my room looks like a bat cave.

Before we get started, a quick heads-up that I’ve unlocked a few of the older Patreon bonus episodes so that anyone can listen to them. They won’t show up in your feed but I have links to the specific episodes in this week’s show notes so you can go listen to them in your browser if you’re interested. You don’t even need a Patreon login. I hope you enjoy them as an extra Halloween treat.

Another reminder that I have a novel available through Fox Spirit Books. It’s called Skytown and it’s a fun steampunk adventure story. I’ll put a link in the shownotes if you want to learn more.

Oh, and if you want a Strange Animals Podcast sticker, just send me your mailing address at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com and I’ll mail you one!

Now, on with the spooky Halloween episode!

This week’s episode is something that has baffled me since I read about it as a kid. It’s baffled everyone for more than 150 years. I’ll tell you now that while I make one suggestion that seems plausible to me, it’s by no means a perfect match for the creature that made…the devil’s footprints.

/reverb reverb reverb

The winter of 1855 was especially bitter in England. Around Devon, the rivers froze solid and temperatures stayed below freezing almost every day and night from January to March. On the night of February 8 it snowed, but towards dawn a brief thaw turned the falling snow to rain before the temperature dropped again and a frost fell. When residents of Devon woke on the morning of February 9, they found some 4” of snow on the ground, or 10 cm. They also found small hoofprints everywhere.

These weren’t ordinary hoofprints. A donkey or pony hadn’t gotten loose during the night and wandered around. Some of the prints did look like a donkey’s, but some appeared cloven, more like a large goat’s hoof. And the stride was short, only about 8” between most prints, or a little over 20 cm, sometimes about double that. Besides, the prints appeared in places where a donkey couldn’t possibly have left prints: on rooftops, inside gardens with tall walls and locked gates. Even a nimble goat couldn’t have managed that without someone hearing a goat bounding around. Sometimes a line of prints would walk right up to an obstacle, like a haystack or hedge, and continue on the other side as though the obstacle didn’t exist. Tracks began or ended abruptly as though the animal had dropped from or flown into the sky.

And there were untold thousands of the prints. Some villages had prints in almost every yard. They appeared in churchyards among gravestones, in gardens and on doorsteps, in fields and roads. They meandered from place to place or sometimes continued in a straight line. And they appeared to be made not by a four-footed animal but by something walking on its hind legs, placing one hoof nearly in front of the other.

People tracked some of the prints for miles without coming across any clue as to what had made them. A few forward thinkers made sketches of the prints and jotted down notes. By February 13, reports of the strange footprints had made it into the local newspapers.

Beyond the often maddeningly vague newspaper accounts, most of what we know about the hoofprints comes from the Reverend H.T. Ellacombe, who was vicar of the parish of Clyst St George from 1850 to 1885. He collected letters and sketches and made his own notes about the event, since some of the prints appeared in his own rectory grounds. Local historian Major Antony Gibbs discovered Ellacombe’s bundle of notes and letters in 1952, tucked away in a church office gathering dust.

But a series of letters published in 1855 by the Illustrated London News has been more influential than Ellacombe’s information. The letters were written by someone who signed himself “South Devon,” and we know from Ellacombe that South Devon was a 19-year-old local man whom Ellacombe called “young D’Urban.”

William D’Urban’s letters were exciting, to say the least. If you’ve heard anything about the devil’s footprints before, it was probably mostly details from D’Urban’s account. According to him, all the prints were identical in size, the stride likewise did not vary, and the prints were one unbroken trail at least 40 miles and as much as 100 miles in length, or 64 to 160 kilometers. This has sometimes been garbled in later retellings as a perfectly straight trail 100 miles long. D’Urban was also the one who claimed the prints continued from one side of the River Exe to the other side, two miles distant. It’s not clear if the river was frozen at this point, although it was frozen so solid by late February that an enterprising stove manufacturer ran pipes from the gas main onto the river ice and cooked an entire dinner for 30 on it while people skated all around him and probably tripped over the gas pipes. Moreover, the river is an estuary of the sea so has tides, and at low tide it’s barely a few hundred yards wide in some areas, or say 200 meters, and barely four feet deep, or about 1.2 meters.

Even at the time, D’Urban’s account was refuted by other locals, whose letters responding to South Devon’s letters were printed in follow-up issues of the paper. Apparently newspapers back then were like really slow social media. People wrote letters in response to other letters they’d seen in the newspaper, and other people wrote letters in response to those letters. Old timey people really needed Facebook. And cameras, because we don’t have very many sketches of the footprints and the ones we do have aren’t very detailed.

So what did the tracks really look like? As far as we know, most of the tracks were about 4 inches long, or 10 cm, and 2.75 inches across, or 7 cm. They did vary in size and shape from place to place, which argues that more than one animal made them and that hoaxers weren’t involved, since hoaxers would leave identical prints. I’ll put Ellacombe’s drawings of the prints, which he copied from newspaper reports, in the show notes to give you an idea of what they looked like. When you hear the word hoofprint it’s easy to think of a crisp, well-marked round hoof, maybe even with a horseshoe, but these prints were kind of wobbly in shape—not unexpected since they were all somewhat distorted by the night’s thaw and refreeze.

One of the people who wrote in to denounce some of D’Urban’s details was a Reverend G.M. Musgrave, vicar of Exmouth, and one of the things Musgrave also mentions is that he himself had suggested to his parishioners that the tracks were made by kangaroos escaped from a private menagerie. But, he admits, he didn’t actually believe this, he was only trying to stop his parishioners from believing that the devil had walked through their town.

The devil only started getting blamed for the footprints once it was clear no one really knew what had caused them. Lots of animals were suggested as culprits, most of which were about as likely as Musgrave’s kangaroos. Among the suggestions were badgers, rats or mice, hares, wolves, cats, monkeys, toads, or various birds. One anonymous letter-writer said that a friend had examined the tracks, noted that some of them showed claw marks, and suggested the animal might be an otter—mostly as a way to explain how the trail passed under low branches without disturbing them and through a six-inch, or 15 cm, pipe.

Other suggestions were even more outlandish, like the runaway balloon trailing a rope theory. Or the complex and largely irrational theory proposed in 1973 that seven Romany tribes conspired to lay the tracks in one night using stilts made from stepladders, in an attempt to scare some other tribes away. Or the 1972 theory that UFOs were measuring…something…with lasers and the tracks were left as a result, by lasers. Measuring things.

Leaving aside the theories that are clearly farfetched, like animals escaped from menageries and UFOs, and going with the assumption that whatever left the tracks was likely a real animal native to England, what might have left the devil’s footprints? I’m going out on a limb and suggesting maybe it wasn’t the devil.

Badgers, otters, and wolves leave tracks much too large to fit the bill. Toads are cold-blooded and would not be active in the snow. Birds do not leave miles of prints in snow at night, not even owls hunting mice on the ground, as they sometimes do. The tracks of deer would probably be recognized no matter how distorted the melting snow might have made them, and there are no reports of dew claw marks that deer prints show.

What about cats? Cats leave small neat footprints in snow with prints nearly in front of each other. With the brief thaw, feral cats might be out hunting for mice and other animals around houses and gardens, exactly where many prints were found. Cats can climb well, and a small cat might be able to accomplish some of the astonishing feats reported, like getting through dense hedges or larger pipes. And we do have a witness whose report is interesting. A tenant of Aller Farm in Dawlish, the only person we know to have been outside during the night in question, said that his cat had left tracks in the snow, and that the thaw and rain melted them, after which they froze again into small hoof-like shapes. So it’s possible that at least some of the prints were made by cats.

Rats sometimes hop through snow on all four feet, leaving deeper impressions that do look remarkably like the hoofprints seen. Rats can also get through quite small spaces and climb well. The main drawbacks of this theory are that hopping rats leave clear tail prints and rats don’t hop for miles. Rats also usually leave prints larger than the ones found. But again, it’s possible that at least some of the prints were made by rats.

Finally, what about mice? When I was a kid, this argument seemed ridiculously weak. I had pet mice. I knew there was no way a mouse could leave a horseshoe shaped print in the snow. But I was only familiar with pet white mice and house mice. There’s a type of mouse common throughout Europe that I think might be our culprit. Let’s find out why, and learn about the wood mouse.

The wood mouse, also called the long-tailed field mouse, is as adorable as the otter but won’t kill you. It’s a cute little rodent with a long tail, sandy-brown or orangey fur, white or gray belly and legs, and big ears. Not counting its tail, it’s about 6 to 15 cm long, or 2 ½ to 6 inches long, and its tail can be as long as its body. It mostly eats seeds and nuts, although it will also eat roots, shoots, berries and other fruit, moss, fungi, snails, and insects when seeds aren’t available.

Like many rodents, it discovered a long time ago that humans are useful nuisances, so it frequently lives around houses and barns, although not usually in houses. It generally lives in burrows it digs in fields, gardens, or among the roots of trees, although sometimes it will make its nest in birdhouses, hollow logs, or in thick vegetation. The nesting chamber of a mouse’s burrow is lined with leaves, grass, and moss, and it may also dig chambers where it stores extra food.

In warm weather wood mice aren’t very social, but in winter they will sleep in pairs or groups to stay warm. They don’t hibernate, but in especially cold weather they become torpid. They’re nocturnal animals, good climbers, jumpers, and swimmers.

While it forages, a wood mouse will pick up small items like leaves and twigs and place them in conspicuous locations to mark certain areas. As far as researchers know, wood mice and humans are the only animals to mark trails with items, known as way-marking. A mouse’s typical winter territory is around 2000 square meters, or half an acre.

All this is interesting, but why do I think the devil’s footprints were mostly made by wood mice? Well, wood mice flee from predators by hopping on all four legs. They’re built like tiny kangaroos, with long hind legs and comparatively short forelegs. I had a hard time finding information about wood mice jumping, just references to their ability to jump sometimes quite long distances. Then I found an awesome site by a photographer with lots of action shots of the wood mice around their garden. I’ll put a link in the show notes. Unfortunately the page hasn’t been updated for a while, but it’s full of photos of mice in mid-leap. The photographer puts food out and apparently sets up cameras that react to movement—like mini trail cams. It’s clear just from these shots that wood mice can and do jump a lot.

Unlike a rat, a jumping wood mouse doesn’t leave much of a tail mark in snow. It can also keep up this hopping gait for a long time, which it would do since it’s a more efficient way to travel through snow taller than the animal is high. It jumps with its feet together so the print it leaves behind roughly resembles a V shape where the two sides of the V don’t connect. Any amount of thawing and refreezing can turn that print into a cloven hoof print or a donkey-like hoof print.

Moreover, mice can get through extremely small holes and pipes, can burrow straight through haystacks, can hop across roofs without making noise. Where people reported finding prints that vanish in the middle of open fields, the mouse could have disappeared into a burrow, been picked off by an owl, or just stopped hopping and started walking, leaving footprints so small and shallow they likely didn’t survive the thaw.

But why were there so many prints on this particular night? Remember, the winter had been harsh but that particular night there was a brief thaw. It’s very possible that even slightly warmer weather would bring hungry mice out in droves to forage. The unusual weather conditions distorting otherwise barely noticeable tracks into hoofprints, and human nature, did the rest.

But if that’s the case, why haven’t people reported seeing the same mysterious prints at other times? Actually, they have, both before and after 1855.

The earliest account anyone has found in the papers was an 1840 report in the London Times of strange prints in Scotland. Other accounts date from the 1850s, 1890, the 1920s, the 1950s, and so on until 2009.

Some of these accounts are of much larger prints, some don’t match up with the hoofprints seen in 1855, but some sound similar. In 1957, for instance, when Lynda Hanson in Hull was a child, a line of cloven hoofprints 4” long and 12” apart appeared in her family’s garden in about an inch of snow that had fallen overnight. They vanished in the middle of the garden. Ms. Hanson notes that the family dog didn’t bark. He probably would have barked at the devil. Just saying.

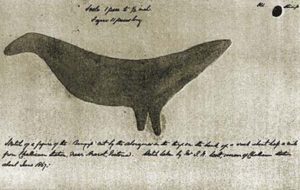

Another interesting report comes from a sighting in late 1962 or early 1963. Zoologist Alfred Leutscher, writing in the April 20, 1965 edition of Animals and expanding on a talk he gave to the Zoological Society of London about the sighting, explains some tracks he found in Epping Forest. I’ll quote from his description. “It was during a search for snow tracks in Epping Forest, in the severe winter of 1962-3, that I came across dozens of trails of the wood mouse, each consisting of small ‘V-shaped’ marks regularly spaced out and conforming to the measurements which were given a hundred years ago. When I found them I was totally unaware of their significance.”

There are problems with this, of course. While the account says the tracks were identical to those reported in 1855, they’re described as V-shaped rather than hooflike. I have no doubt Leutscher’s prints were from wood mice, but whether they were the same type of thing seen in 1855 in Devon, we can’t know for sure since the reports from the 1855 sighting are so unclear.

Like I said, while the wood mouse is a good candidate for what caused the devil’s footprints, it’s not perfect. Why would mice be hopping around on snow-covered roofs, for instance? But nothing else fits the evidence we have as well as the wood mouse does.

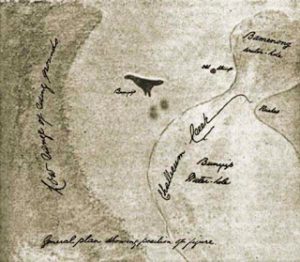

In 2009, Jill Wade of North Devon woke up to snow and found a line of hoof-like prints across her garden. A zoologist who examined the prints suggested they might be those of a rabbit or hare, although since the prints were only 5” long, or 12.5 cm, that would have to be a little baby bunny. But the great thing in this case is we have photographs. Good ones. I’ll put one in the show notes. It definitely looks like a hoofprint—and it also looks like little animal legs made it.

One interesting thing. The wide part of a wood mouse’s print, the one that would make the rear of a hoofprint, is actually at the animal’s front. So anyone following the devil’s tracks in 1855 was following them backwards. Assuming the culprit really was a horde of hungry wood mice, and not the actual devil.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on iTunes or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way. Rewards include stickers and twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening, and Happy Halloween!