Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:21 — 13.5MB)

Thanks to Pranav for this week’s suggestion! We’re going to look at three mystery animals from India, ones you may not have heard of.

A photograph reportedly of a kallana pygmy elephant, although scale is hard to tell:

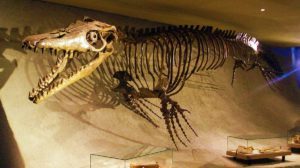

A pink-headed duck, deceased:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s time for a mystery animals episode, and this one was a suggestion from Pranav, who suggested mystery animals from India. Pranav also gave me lots of other excellent suggestions that I’ll hopefully get to pretty soon.

When I got the suggestion, I realized the only mystery animal from India I really knew about was one we talked about in episode 55, the buru. I had no idea what else might be hiding in the forests and mountains of India. Apologies in advance for undoubtedly mangling names and places from India. I tried to look up pronunciations to at least make an effort to get them right.

India is in south Asia, and it’s a huge country. The area is often referred to as the Indian subcontinent because it mostly sits on its own tectonic plate. Around 100 million years ago it was connected with Madagascar, then split off around 75 million years ago and for many millions of years it was a giant island. But it moved northward slowly—and we’re talking only around 8 inches a year, or 20 cm, which is actually pretty fast for a tectonic plate—and slowly crashed into Eurasia, shoving beneath the Eurasian plate and causing it to crumple upwards, creating the Himalayas.

About half of India’s landmass projects southward into the Pacific Ocean like someone dipping their foot into a bath to see if it’s too hot. As a result, the country has a lot of coastland. So there are amazingly high mountains to the north, tropical coasts to the south, and everything from desert to tropical rainforest in between. It even has some volcanic islands off its coast. It pretty much has everything you could want in a country, and that means it has an amazing variety of animal life too.

Many of India’s animals are ones everyone is familiar with from zoos and storybooks: elephants, tigers, rhinoceroses, cobras, pangolins, and lots lots lots more. But it also has its share of mystery animals. We’ll look at three of those mystery animals today. I think you’re going to like all three of them.

Let’s start with the mande burung. It’s supposed to be a giant ape-like animal as much as 8 or 10 feet tall, or up to 3 meters, with black hair. It lives in the remote forests of northeast India—specifically, in Meghalaya.

The mande burung has long been a creature of folklore in the area, until November 1995 when someone saw one. But I can’t find any information at all about what that sighting entailed. Interest in the mande burung has increased steadily since then, with cryptozoologists from India and other parts of the world mounting expeditions to look for it. They report finding footprints up to 15 inches long, or 38 cm, hair from unidentified animals, and nests made from leaves and grass. But there are no photographs of the animals, no mande burung feces, no dead bodies, and very few sightings, all of them within the last few decades and some of them decidedly questionable.

It’s certainly possible that there’s a mystery animal living in the area. Meghalaya is heavily forested outside of the cities and farmland. Some areas of forest are considered sacred, so they’ve never been logged, no one’s ever lived there, and no one hunts there. As a result, these sacred forests contain some of the richest habitats in all of Asia, containing plants and animals that live nowhere else. Meghalaya also has wildlife sanctuaries. So it’s pretty much guaranteed that there are animals living in Meghalaya that are unknown to science.

But while Meghalaya is primarily an agricultural region, tourism is becoming more and more important. A 2007 press release even talks about how the mande burung legend will bring more tourists to the area, and that a local group had started offering tours for people looking for the mande burung. That doesn’t mean the sightings aren’t genuine—I think most of them are—but as I’ve said many times, people see what they expect to see. The more people talk about the mande burung, the more likely people will think of it when they see a large animal they can’t identify. And there are lots of big animals living in the forests of Meghalaya, including an endangered species of gibbon, four species of macaque, and three species of bears. Any of these might resemble a bigfoot type of creature if seen in low light or poor conditions.

In 2001, a hair found in what’s called a “cedar tree root den” was DNA tested. Bear and human DNA was ruled out, and the DNA results didn’t match any known animals. But a follow-up test in 2008 gave a result that was just as surprising to scientists: the hair belonged to a Himalayan goral, a bovid that wasn’t known to live in the area until the DNA results came in. The goral is a small antelope-like animal with short horns that lives in the southern slopes of the Himayalas. It’s dark gray or gray-brown in color with a darker eel stripe along the spine. Generally, websites that like to talk about Bigfoots mention the first DNA test but don’t mention the follow-up, but I think the discovery of Himalayan goral hairs in Meghalaya is exciting. Who knows what else might be hiding in the forests too?

For instance, maybe a pygmy elephant! Well, okay, reports of a suspected dwarf elephant species called the kallana come from southern India, not northeastern. But it’s definitely a mystery animal.

The Indian elephant is a subspecies of Asian elephant that lives throughout much of mainland Asia. It’s smaller than the African elephant but still pretty big, with males standing as much as 11.3 feet at the shoulder, or 3.4 meters, although most are much smaller than this. Females are smaller than males and have smaller tusks, or sometimes no tusks. It was once common throughout India but is now endangered due to habitat loss and poaching. Tame elephants help with farming and with carrying heavy items and human riders across uneven terrain, but the elephants aren’t actually domesticated.

The kallana elephant reportedly only grows to around five feet high, or 1.5 meters, and while it looks like an ordinary Indian elephant except for its size, it doesn’t mix with Indian elephants and even appears to avoid them. It lives in rocky hills in and around the Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary in southern Kerala. It’s shy and can move much faster than regular elephants, and it doesn’t appear to have trouble with steep slopes the way elephants usually do.

In 2005, a wildlife photographer named Sali Palode got pictures of two kallana elephants, one alive, one a dead one they found by a lake. He took more photos in 2010, and in 2013 he got brief video footage. But there are no photos of a herd of kallana elephants, just solitary animals. Without being able to examine a kallana elephant in person, researchers don’t know if the elephant photographed is a new species or subspecies, or just an Indian elephant with a genetic anomaly similar to dwarfism in humans. The photos might even just be of young elephants that haven’t grown to their full size yet.

Until someone gets definitive footage of a herd of Kallana elephants, an individual is captured and studied, or someone takes samples of the elephant dung found throughout the hills and sends it for DNA testing, there’s no way of knowing if the small elephants Sali Palode has photographed and the local tribespeople report seeing are something special. Not that regular elephants aren’t special enough already, but if there is a population of anomalous elephants in the area, it’s important to learn about them so they can be further protected.

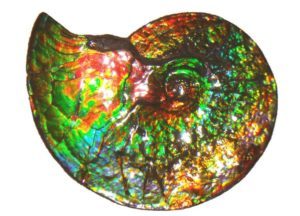

Our final mystery animal of India is the pink-headed duck. It lives in wetlands in parts of eastern India and a few nearby countries, and it gets its name because the male has a pink head and neck. It builds its nests in dense elephant grass and its eggs are almost completely round. It’s shy and prefers remote, isolated areas with deep ponds or lakes and thick grass.

So why are we talking about the pink-headed duck in a mystery animals episode? Well, unfortunately, there hasn’t been a single confirmed sighting of the duck since 1949. Some researchers push this back ever farther to 1935. The main reason it hasn’t been classified as extinct is that the occasional report of one occasionally trickles in.

The difficulty in knowing whether there really are pink-headed ducks still alive out there is that the areas where they are known to have lived are really hard to get to. I mean, unless you’re a duck. Then they’re great. The decline of the species started in the 19th century when British big game hunters would come through and basically just shoot everything that moved. It was already considered rare by the turn of the 20th century, which made hunters even more eager to shoot it so they’d have a rare trophy. Habitat loss and trophy hunting drove it nearly to extinction even if it’s not actually already extinct.

Recent expeditions by conservationists and birders hoping to find some pink-headed ducks haven’t found any definitive proof that any are still alive. A 2017 expedition to Myanmar didn’t find any of the ducks, but the team did interview locals who said they’d seen the ducks as recently as 2010.

We don’t know a whole lot about the pink-headed duck. Researchers think it was a diving duck, but it may have been a dabbler. A dabbling duck tips its body forward, head underwater and tail sticking up, to forage in shallow water, often on plants. A diving duck dives for its food, usually small animals of various kinds. We know the pink-headed duck ate snails and plants, but it probably ate other things too that we don’t know about.

A study of a taxidermied pink-headed duck’s feathers in 2016 determined that the pink color came from carotenoids, a pigment that also gives the flamingo its pink color. The only other duck with feathers pigmented by carotenoids is the pink-eared duck of Australia, which is only distantly related to the pink-headed duck. It has a tiny pink spot on each side of its head.

Conservationists and birdwatchers hold out hope that the pink-headed duck is still alive, hiding its round eggs in clumps of elephant grass far away from humans. Some researchers have even suggested it might be nocturnal, which would explain why it’s always been hard to find. It was never much of a duck for moving around, preferring to stay put instead of flying off to other areas. Hopefully someone will discover a healthy population one day, possibly somewhere no one’s even looked yet, and we can protect it and learn about it before it’s too late. Once a duck is gone, a duck is gone forever.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!