Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:35 — 15.5MB)

This week is our six-month anniversary! To celebrate, we’ll learn about some of the creatures that live at the bottom of the Mariana Trench’s deepest section, Challenger Deep, as well as other animals who live in deep caves on land. We also learn what I will and will not do for a million dollars (hint: I will not implode in a bathysphere).

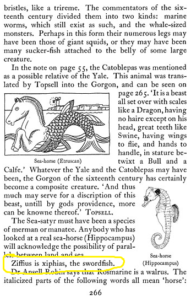

A xenophyophore IN THE GRIP OF A ROBOT

A snailfish from five miles down in the Mariana trench:

The Hades centipede. It’s not as big as it looks, honest.

The tiny but marvelous olm.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

For this week’s episode, we’re going to find out what lives in the deepest, darkest places of the earth—places humans have barely glimpsed. We’re not just talking deep sea, we’re talking the abyssal depths.

Like onions and parfaits, the earth is made up of many layers. The core of the earth is a ball of nickel and iron surrounded by more nickel and iron. The outer core is molten metal, but the inner core, even though it’s even hotter than the outer core—as hot as the surface of the sun—has gone through the other side of liquid and is solid again. Surrounding the core, the earth’s mantle is a thick layer of rocks and minerals some 1900 miles deep, and on top of that is the crust of the earth, which doesn’t actually sound very appealing but that’s where we live and we know it’s really pretty, with trees and oceans and stuff on top of it. The upper part of the mantle is broken up into tectonic plates, which move around very slowly as the molten metals and rocks beneath them swirl around and get pushed up through cracks in the mantle.

Under the oceans, the crust of the earth is only around 3 miles thick. And in a few places, there are crevices that actually break entirely through the crust into the mantle below. The deepest crack in the sea floor is the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific. At its deepest part, a narrow valley called Challenger Deep, the crack extends seven miles into the earth.

The pressure at that depth is immense, over 1,000 times that at sea level. Animals down there can’t have calcium carbonate shells because the pressure dissolves the mineral. It’s almost completely dark except for bioluminescent animals, and the water is very cold, just above freezing.

The trench is crescent shaped and sits roughly between Japan to the north and Papua New Guinea to the south, and the Philippines to the west. It’s caused by the huge Pacific plate, which is pushing its way underneath the smaller Mariana plate, a process called subduction. But near that activity, another small plate, the Caroline plate, is subducting beneath the Pacific plate. Subduction around the edges of the Pacific plate is the source of the earthquakes, tsunamis, and active volcanos known as the Ring of Fire. Some researchers think there’s a more complicated reason for Mariana Trench and other especially deep trenches nearby, though. There seems to be a tear in the Caroline plate, which is deforming the Pacific Plate above it.

Challenger Deep is such a deep part of the ocean that we’ve barely seen any of it. The first expedition that got all the way down was in 1960, when the bathyscape Trieste reached the bottom of Challenger Deep. This wasn’t an unmanned probe, either. There were two guys in that thing, Jacque Piccard and Don Walsh, almost ten years before the moon landing, on a trip that was nearly as dangerous. They could see out through one tiny thick window with a light outside. The trip down took almost five hours, and when they were nearly at the bottom, one of the outer window panes cracked. They stayed on the bottom only about 20 minutes before releasing the weights and rising back to the surface.

The next expedition didn’t take place until 1995 and it was unmanned. The Kaiko could collect samples as well as record what was around it, and it made repeated descents into Challenger Deep until it was lost at sea in 2003. But it not only filmed and collected lots of fascinating deep-sea creatures, it also located a couple of wrecks and some new hydrothermal vents in shallower areas.

Another unmanned expedition, this one using a remotely operated vehicle called the Nereus, was designed specifically to explore Challenger Deep. It made its first descent in 2009, but in 2014 it imploded while diving in the Kermadec Trench off New Zealand. It imploded. It imploded. This thing that was built to withstand immense pressures imploded.

In 2012, rich movie-maker James Cameron reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the Deepsea Challenger. He spent nearly three hours on the bottom. Admittedly this was before the Nereus imploded but you could not get me into a bathysphere if you paid me a million dollars okay well maybe a million but I wouldn’t do it for a thousand. Maybe ten thousand. Anyway, the Deepsea Challenger is currently undergoing repairs after being damaged in a fire that broke out while it was being transported in a truck, which is just the most ridiculous thing to happen it’s almost sad. But it’s still better than imploding.

In addition to these expeditions, tethered cameras and microphones have been dropped into the trench over the years too. So what’s down there that deep? What have these expeditions found?

The first expedition didn’t see much, as it happens. As the bathyscape settled into the ooze at the bottom of the trench, sediment swirled up and just hung in the water around them, unmoving. The guys had to have been bitterly disappointed. But they did report seeing a foot-long flatfish and some shrimp, although the flatfish was more likely a sea cucumber.

There’s actually a lot of life down there in the depths, including amphipods a foot long, sea cucumbers, jellyfish, various kinds of worms, and bacterial mats that look like carpets. Mostly, though, there are Xenophyophores. They make big delicate shells on the ocean bottom, called tests, made from glued-together sand grains, minerals like lead and uranium, and anything else they can find, including their own poops. We don’t know a lot about them although they’re common in the deep sea all over the world. While they’re unicellular, they also appear to have multiple nuclei.

For the most part, organisms living at the bottom of the Challenger Deep are small, no more than a few inches long. This makes sense considering the immense water pressure and the nutrient-poor environment. There aren’t any fish living that deep, either. In 2014 a new species of snailfish was spotted swimming about five miles below the surface, a new record; it was white with broad fins and an eel-like tail. Snailfish are shaped sort of like tadpoles and depending on species, can be as small as two inches long or as long as two and a half feet. A shoal of Hadal snailfish were seen at nearly that depth in 2008 in the Japan Trench.

While there are a number of trenches in the Pacific, there aren’t very many deeps like Mariana Trench’s Challenger Deep—at least, not that we know of. The Sirena Deep was only discovered in 1997. It’s not far from Challenger Deep and is not much shallower. There are other deeps and trenches in the Pacific too. But like Challenger Deep, there aren’t any big animals found in the abyssal depths, although the other deeps haven’t been explored as much yet.

In 2016 and early 2017, NOAA, the U.S. Coast Guard, and Oregon State University dropped a titanium-encased ceramic hydrophone into Challenger Deep. To their surprise, it was noisy as heck down there. The hydrophone picked up the sounds of earthquakes, a typhoon passing over, ships, and whalesong—including the call of a whale researchers can’t identify. They think it’s a type of minke whale, but no one knows yet if it’s a known species we just haven’t heard before or a species completely new to science. For now the call is referred to as the biotwang, and this is what it sounds like.

[biotwang whale call]

But what about animals that live in deep places that aren’t underwater? It’s actually harder to explore land fissures than ocean trenches. Cave systems are hard to navigate, frequently extremely dangerous, and we don’t always know how deep the big ones go. The deepest cave in the world is Krubera Cave, also called Voronya Cave, in Georgia—and I mean the country of Georgia, not the American state. Georgia is a small country on the black sea between Turkey and Russia. So far it’s been measured as a mile and a third deep, but it’s certainly not fully explored. Cave divers keep pushing the explored depth farther and farther, although I do hope they’re careful.

We’ve found some interesting animals living far beneath the earth in caves. The deepest living animal ever found is a primitive insect called a springtail, which lives in Krubera cave and which was discovered in 2010. It’s pale, with no wings, six legs, long antennae, and no eyes. There are a whole lot of springtail species, from snow fleas to those tee-tiny gray bouncy bugs that live around the sink in my bathroom no matter how carefully I clean. All springtails like damp places, so it makes sense that Krubera cave has four different species including the deepest living one. They eat fungi and decomposing organic matter of all kinds. Other creatures new to science have been discovered in Krubera cave, including a new cave beetle and a transparent fish.

A new species of centipede was described in 2015 after it was discovered three-fourths of a mile deep in three different caves in Croatia. It’s called the Hades centipede. It has long antennae, leg claws, and a poisonous bite, but it’s only about an inch long so don’t panic. Also it lives its entire life in the depths of Croatian caves so you’re probably safe. There are only two centipedes that live exclusively in caves and the other one is named after Persephone, Hades’ bride. It was discovered in 1999.

A cave salamander called an olm, which in local folklore was once considered a baby dragon, was recently discovered 370 feet below ground in a subterranean lake, also in Croatia. It’s a fully aquatic salamander that only grows a few inches long. Its body is pale with pink gills. It has eyes, but they’re not fully developed and as it grows, they become covered with layers of skin. It can sense light but can’t otherwise see, but it does have well-developed electroreceptor skills, hearing, smell, and can also sense magnetic fields. It eats snails, insects, and small crustaceans and has very few natural predators.

In 1952 researchers created an artificial riverbed in a cave in France that recreates the olm’s natural habitat as closely as possible. The olms are fed and protected but not otherwise interacted with by humans. There are now over 400 olms in the cave, which is a good thing because in the wild, olms are increasingly threatened by pollution, habitat loss, and unscrupulous collectors who sell them on the pet trade black market.

Olms live a long, long time—probably 100 years or longer. Some individuals in the artificial riverbed are 60 years old and show no signs of old age. Researchers aren’t sure why the olm lives so long. We don’t really know a whole lot about the olm in general, really. They and the caves where they live are protected in Croatia.

There are a few places in the world where people have drilled down into the earth, usually by geologists checking for pockets of gas or water before mining operations start. In several South African gold mines, researchers found four new species of tiny bacteria-eating worms, called nematodes, living in water in boreholes a mile or more deep. After carefully checking to make sure the nematodes hadn’t been introduced into the water from mining operations, the researchers theorized the nematodes already lived in the rocks but that the boreholes created a perfect environment for them. Nematodes are well-known extremophiles, living everywhere from hot springs to the bellies of whales. They can withstand drought, freezing, and other extreme conditions by reverting to what’s called the dauer stage, where they basically put themselves in suspended animation until conditions improve.

The boreholes also turned up some other interesting creatures, including flatworms, segmented worms, and a type of crustacean. They’re all impossibly tiny, nearly microscopic.

If you go any deeper, though, the only living creatures you’ll find are bacteria and other microbes. In a way, though, that’s reassuring. The last thing we want to find when we’re poking around in the world’s deepest cracks is something huge that wants to eat us.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on iTunes or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way. Rewards include stickers and twice-monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!