Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 31:28 — 32.2MB)

Subscribe: | More

It’s almost Halloween, and time for another spooky episode! Thanks to Pranav for the suggestion!

You still have time to enter the book giveaway contest, deadline October 31, 2020 at midnight! Details are here. There are also links on that page to look at the books if you want to order copies. You know, just in case.

I was a guest cohost on the Varmints! podcast again, and this time we talked about ticks! Listen here if you don’t already subscribe (but you should totally subscribe).

Further reading:

The Demon of Dover

Decades later, the Dover Demon still haunts

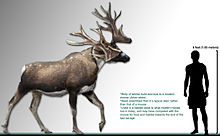

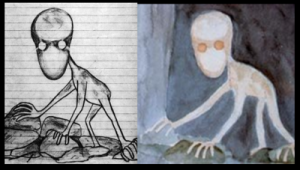

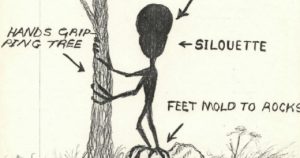

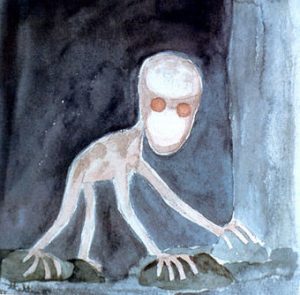

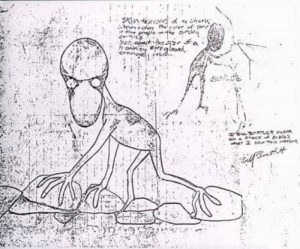

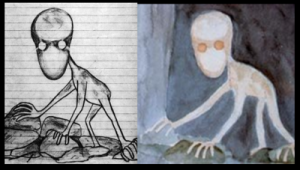

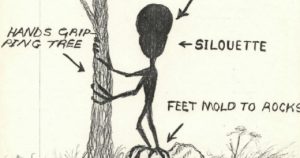

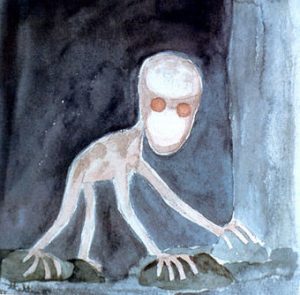

Bill Bartlett’s drawings and painting:

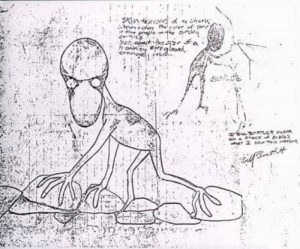

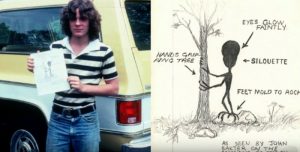

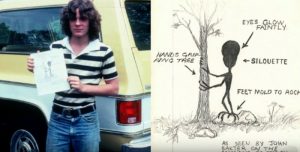

John Baxter’s drawing:

A baby moose (and mama moose):

A sad mangy bear:

An orangutan with cheek pads (a sign of a dominant male):

The sad mangy bear photo side by side with the (flipped) drawing of the Dover demon:

Without much hair on the feet, a bear’s claws might make the digits look elongated:

At night and at certain angles, a bear’s ears may not be very visible (also note eyeshine):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s almost Halloween and I’m really excited, because we’re going to talk about a spooky encounter with a mystery creature called the Dover Demon. It’s a suggestion by Pranav that seemed perfect for monster month.

First, though, I was a guest cohost on Varmints! podcast again last week, and we talked about ticks! It’s a really funny episode so you should totally go listen to it. I’ve put a link in the show notes. You really should subscribe to the podcast, though, because all the episodes are fun and informative!

Dover, Massachusetts is a small town in northeastern North America, only about 15 miles from the city of Boston. Currently just over 6,000 people live there, up from about 5,000 people in 1977. It’s an affluent town with good schools, a small museum, and a number of historic homes. But it’s most well known for something weird that happened over forty years ago.

On the night of April 21, 1977, three seventeen-year-old boys were driving along Farm Street on the outskirts of town. Bill Bartlett was driving with his friends Mike and Andy in the car with him. This was long before the internet or video games or even cable TV were invented, so they were just driving around and talking since they had nothing better to do. It was a Thursday night and cooling down after an unusually warm day for late April in that part of North America.

Around 10:30pm, as they passed along a low stone wall on the left side of the road, Bill noticed an animal of some kind climbing on the stones. He thought it was a dog or even a cat at first, but then the car’s headlights lit it up. Bill saw the creature turn its head and stare into the light.

The creature was definitely not a dog. It had big round eyes that shone like orange marbles, as Bill described it later. He estimated it would have been four feet tall if it had been standing upright, or 122 cm. It had peach-colored skin that looked like it might have a rough texture, which Bill later described as looking like wet sandpaper or a shark’s skin. Its body was thin, its arms and legs were very long and thin, and it had a thin neck. But its head was oversized and oddly shaped. Bill described it as shaped like a melon, but to me it always sounds more like Snoopy the dog’s head. You know, Snoopy has a round head and a big oblong nose in comparison to a little body. But this creature wasn’t a cartoon character, it was real. Bill said it had long, thin fingers and toes that it wrapped around the rocks as it climbed over them. But while it did have those big glowing eyes, it didn’t appear to have ears, nose, or mouth.

The other two boys in the car were talking and didn’t notice the creature as the car passed it going somewhere around 45 mph, or 72 km/h. Bill was naturally freaked out and after about three quarters of a mile, or a little over a km, he stopped the car to tell his friends what he’d seen. They talked it over for a good 15 minutes before deciding to turn around and go back to look for the creature. But they didn’t see it again, so Bill dropped his friends off at their homes, then went home himself.

Bill’s father noticed that he seemed upset and Bill admitted that he’d seen something that had spooked him. He made a drawing of the creature and later made another drawing and a watercolor of it. Bill was a good artist and in fact when he grew up he became a professional artist. Photos of his drawings of the creature are in the show notes.

A few hours later that same night, at about 12:30 AM, another boy, fifteen-year-old John Baxter, was walking home from his girlfriend’s house on Miller Hill Road. Miller Hill Road intersects Farm Street, the road where Bill saw the creature, and John was about a quarter mile, or .4 km, away from where the two roads met when he noticed another person on the road ahead. He noticed the figure’s large head and thought it was a friend who lived nearby, a boy who actually had a deformed head due to a childhood illness. John called out to him but didn’t get a response. As John came closer, he noticed how small the other figure’s body was in comparison to its head and realized it wasn’t his friend. He thought it might be a small child.

The figure suddenly ran off the road. John heard it run down a small embankment at the edge of the road and into the trees. He chased it but stopped at the bottom of the embankment, since he hadn’t realized there was a creek at the bottom and almost fell in. The creature must have jumped the creek because John specifically mentioned that he didn’t hear it splashing through the water.

At this point John got a good look at the creature, since it had stopped about 30 feet away, or 9 m, and was looking back at him. It was in silhouette against an open field, with its head about level with John’s because of the way the ground sloped. It had a small, slender body, long, thin arms and legs with long, thin fingers and toes, and an oversized head with the same unusual shape that Bill reported. John said that the creature was standing on a rock and he could see that its long toes were wrapped around the rock, while it had also wrapped its long fingers around the trunk of a small tree.

Naturally, John got spooked at that point and backed off. He hurried to Farm Street and found someone to give him a ride home instead of walking the rest of the way. Later he made a sketch of what he’d seen.

The next night, a fifteen-year-old girl named Abby Brabham reported seeing something weird on Springdale Avenue. Springdale also joins Farm Street and is less than a mile from Miller Hill Rd. Abby was riding in the car with an eighteen-year-old friend, Will Taintor, who was driving her home, when she noticed something crouched next to the road at the edge of a bridge. I looked on street view and don’t see anything that could be called a bridge, but there are a lot of swampy areas near the road so there may have been a low bridge there in 1977. At first Abby thought she was looking at an ape, but it had a tan body without hair, a large watermelon-shaped head, and glowing green eyes. Will saw the creature too, although not as good a look as Abby. Abby estimated that the creature was the size of a goat.

And that’s that. The creature was never seen again.

OH MY GOSH THAT IS SO CREEPY.

In a case like this, where we’re presented with accounts from four people who saw something truly weird and report specific details that tally with each other, we can look at it logically this way. It’s either a hoax, a known animal that wasn’t identified at the time, an unknown animal, or something supernatural.

Let’s start with the assumption that it was a real animal, either known or unknown. (We’ll come to the other parts later.) If that’s the case, what kind of animal might it be?

People have suggested that the animal might have been a moose calf that got separated from its mother and was blundering around scaring teenagers. But a moose as the culprit doesn’t make any sense. Moose have big ears and nostrils, hooves instead of long fingers and toes, and a calf’s head actually appears small in relation to its bulky body and extremely long legs. But most importantly, there weren’t any moose living anywhere in Massachusetts in 1977. Now that there are moose in Massachusetts, you’d think that people would start seeing the Dover Demon again if it was actually a young moose, but that hasn’t happened.

A more likely possibility is a young black bear. Bears do stand and sometimes walk on their hind legs, especially young ones. But bear paws are broad and flat, and their toes are close together, sort of like a person’s toes. Not only that, bears have large ears. And, of course, they have thick black fur. Bears do get a type of mange that can cause them to lose their hair, and a young bear with a case of mange that advanced would probably also be sick and possibly very thin. But hairless bears, in addition to looking very sad, appear to have small heads, and their ears stick out even more than usual since they’re not half hidden with fur.

Could the creature be a primate of some kind? Abby said she thought she was looking at an ape at first, while in his interview John said he thought the creature might be a monkey. Obviously neither monkeys nor apes would ordinarily be found in Massachusetts, but exotic animal laws were more lax in 1977 than they are now. Not only that, there are some primate research facilities in and near Boston.

A monkey would have the long, thin limbs and slender body seen by witnesses, and it could wrap its fingers and toes around rocks. But there are problems with the monkey hypothesis. Monkeys generally have small heads, not oversized ones. Most have tails. Monkeys are also diurnal so wouldn’t be running around at night, and even if it was out at night for some reason, it would likely stay in the trees or climb a tree if someone frightened it.

Apes, of course, have no tails and they have relatively long limbs and fingers and toes. But it’s much less likely that an ape would escape from someone’s home or from a research facility and not be reported missing. For one thing, apes are expensive and can be dangerous. The research facilities I looked up didn’t seem to keep apes, just monkeys of various kinds.

It couldn’t have been a gorilla since a gorilla’s face is always gray or black with pronounced nostrils, and gorillas are much larger than what witnesses reported seeing, with a bulky body. Chimps are closer to the right size, but chimps don’t have big heads compared to their bodies—in fact, they’re proportioned more like humans but with smaller heads.

But what about an orangutan? Leaving aside the issue of where it came from and why it was never reported missing, could an orangutan have been the Dover Demon? Dominant male orangutans develop large cheek pads and throat pouches that can make their heads look quite large, and most orangs have orange fur that might look like tan textured skin in the dark. But orangutans have noticeable mouths and nostrils, plus their eyes are much closer together than the drawings indicate.

And there’s something else that indicates the Dover Demon probably wasn’t a primate. Many animals have a reflective layer in the eye that causes eyeshine at night. It’s called the tapetum lucidum and it helps animals see better at night. But humans, apes, and monkeys are diurnal animals and don’t have that particular night-time adaptation. All the witnesses said that the creature’s eyes glowed, presumably with reflected light.

That brings us to Abby’s sighting. Abby reported that the creature she saw had glowing green eyes, whereas Bill and John both said the creature they saw had orange glowing eyes. Abby refused to change her story, either, and was adamant that the eyes she saw were green.

Different animals have different-colored eyeshine, and individuals of the same type of animal may have different color eyeshine depending on lots of factors. But the color of an individual animal’s eyeshine doesn’t change from one night to the next. Is it possible that Abby didn’t see the same creature that Bill and John did? She didn’t get a good look at it, and Will barely got a glance. But I’ve always wondered why Abby said the creature she saw was the size of a goat. While that is a good description, unless Abby was familiar with goats and saw them frequently, it’s surprising that she didn’t describe it as the size of a big dog. I wonder if Abby actually saw a tan or light brown goat by the side of the road but didn’t recognize it consciously. Goats do have green eyeshine.

Then again, Abby described the creature’s head as very big and very weird, specifically watermelon-shaped, and she specified that it had a tan, hairless body and round eyes. All these things tally with what the others reported.

So if it wasn’t a known animal, could it have been an unknown animal, something new to science? Let’s assume it was, for now, and try to figure out what kind of habitat an animal of the Dover demon’s appearance would belong in.

However strange it appeared to the witnesses, the creature had four legs and a head. That means it fits the general body scheme of a tetrapod and a vertebrate. Witnesses reported seeing both fingers and toes, so it wasn’t a bird. It appeared to have a tapetum lucidum so it must be nocturnal to at least some degree. It was able to move around on land rapidly, apparently could walk on its hind legs alone if necessary since John Baxter mistook it for a person on the road, but it also seemed more comfortable when its front legs were braced against something, such as a rock or a tree. John didn’t hear it splash in the water when it ran down the embankment, so it could jump as well as run. It also didn’t escape by climbing a tree or hiding in the water when it was frightened, so we can assume it was a terrestrial animal, meaning it was most comfortable on land. It was either a mammal, a reptile, or an amphibian, but I think we can discount the amphibian hypothesis since it avoided the water. It didn’t appear to have fur, and its skin had a textured appearance, which might suggest that it was some kind of reptile instead of a mammal. But all reptiles have tails, and our creature didn’t appear to have one. That means the Dover demon was most likely a mammal.

So we have narrowed it down to a nocturnal, terrestrial mammal that either doesn’t have hair, or that was suffering from an advanced case of mange. Let’s assume that it just doesn’t have hair, or has hair that wasn’t visible at night. The hair might have been short and dense, like seal fur, so that it appeared to be textured skin, or it might have been very finely haired, sort of like a human’s body.

But the witnesses agreed that the creature was pale in color, a sort of tan or peach. That’s where it gets trickier, because that’s an unusual trait in a nocturnal animal. Pale skin or hair reflects light, which makes the animal easier to see in the darkness. That’s great if you’re a skunk and want to call attention to yourself so other animals can avoid your amazing stink powers, not so great if you’re trying to slink around unseen.

There are only a few habitats where it doesn’t matter what color an animal is, and those are habitats where the animal can’t be seen. Maybe the Dover demon ordinarily lives underground or in a cave.

Animals that live underground have to be able to dig, or else they’re not going to get very far. That means they need large claws. They also tend to have smaller eyes, since they can’t see far anyway and more dirt will get into large eyes. They also have short legs. So I think we can safely say that the Dover demon wasn’t an animal that spent much or any time burrowing underground.

But maybe it was a cave-dwelling animal. It had big eyes and a tapetum lucidum to take advantage of low light and it navigated quickly over rocks, wrapping its long fingers and toes around them. That makes sense, because those fingers and toes, as well as the long limbs, suggest an animal that can climb. Maybe it climbed around in caves.

So we seem to have found the most reasonable habitat for what we know about the Dover demon. It may be an animal adapted for climbing around in caves. Perhaps its oversized head acts as a resonant chamber to help it navigate with a type of echolocation when there’s no light, the way many whales have bulbous foreheads called melons.

But it doesn’t fit exactly, so let’s go over the drawbacks of our cave-dwelling mammal hypothesis.

First, there aren’t very many caves in Massachusetts. Only about 14,000 years ago, all of northern North America, including what is now Massachusetts, was covered with glacial ice many miles deep. The glaciers scraped away soil and the softer rock where caves form, and when they finally melted, they left exposed tough bedrock behind. What few natural caves there are in the area are quite small.

But all that side, the Dover demon was a large animal. If you’ve listened to episode 121, about cave dwelling animals, you may remember that large animals don’t live exclusively in caves because there’s just not enough food for them. There are no mammals known that live only in caves. Bats roost in caves but they come outside at night to hunt, and many other animals hibernate or sleep in caves but spend the rest of their time outside.

Now let’s look at our other two choices: either it’s a hoax or it’s something supernatural.

I don’t like to label mystery animals as supernatural. You’re not solving a mystery by labeling it as a different mystery. Some people have suggested that the Dover demon was actually an extraterrestrial that got separated from its space ship, and I considered this hypothesis carefully. But the Dover demon acted like an animal and has the body plan of an animal that is from Earth. If it hadn’t look so spooky—if it had fur—no one would have thought it was especially unusual.

So, was it a hoax? The witnesses all went to the same high school and lived in the same small town, although Abby was actually from another small town adjacent to Dover. Bill and Will were good friends, but Bill and John only knew each other slightly. None of them went to the newspapers or tried to make a big deal of their sightings. There’s some confusion as to when they realized they’d all seen the same thing and compared stories, but it seems to have happened either the next day when Bill and Will gave John a ride, on Saturday when John and Bill both attended the same party, or the following Tuesday at school.

I’ve put a link in the show notes to a really good site where I took a lot of my information, which itself is taken directly from the original interviews and report by a group of cryptozoologists, including Loren Coleman, who was the one who started calling the creature the Dover demon. There’s a long quote from John Baxter, and the way he describes what happened sounds authentic to me. I also read a 2006 interview with Bill Bartlett and he still claims the sighting was authentic.

Could it have been a thin person or a little kid with a big mask on, out at night to scare people? Of course this is possible, but why did the person quit after just three separate sightings on two nights? Reports of the sightings didn’t make it to the newspapers until the following month, so it’s not like there were people out hunting for the creature and the hoaxer was afraid they’d be caught.

There is one detail that concerns me about the sightings. April 18, 1977 was a new moon, which means that April 21 would have been quite dark, with only a thin crescent moon. Yet both Bill and John reported seeing the creature’s long fingers and toes wrapped around rocks. Bill did see the creature in his car’s headlights, but John was looking at it through the trees. I checked Google Maps street view again and Miller Hill Road doesn’t appear to have streetlamps, so I don’t know how John could have seen the creature’s fingers and toes so clearly from 30 feet away on a nearly moonless night.

I wish we had better information about when John made his drawing. His drawing is very, very similar to Bill’s, so much so that I wonder if John saw Bill’s first and used it as a reference. While John did obviously have some artistic ability, his lines aren’t as sure as Bill’s and he may have been uncertain both about the details he’d seen and about his ability to draw the details accurately. He might have filled in the gaps in his memory by looking at Bill’s drawing.

It does seem suspicious that three of the four witnesses were close friends: Bill and Will were buddies, and Abby was Will’s girlfriend. John knew the others but wasn’t friends with them, but that doesn’t mean they couldn’t have asked him to be part of the joke. Bill and Will were older and John might have looked up to them, and he might have been flattered to be part of the hoax.

I keep coming back to Bill’s drawings of the creature. He made several, apparently illustrating what he’d seen since the poses are all similar. But I’m an artist myself, and sometimes when you draw something really interesting you redo it several times because you like it and you want to improve it. You can get really attached to a character you doodled randomly. I wondered for a while if Bill’s drawings came first, and the story came second as a way to get more people to look at his drawings and appreciate the character he created. Or he might have been illustrating Gollum, the creature from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The books were really popular even then and the drawing does look a lot like the way Gollum is described in the books.

But I finally rejected this. From what we know of Bill’s character, this wasn’t something he would do. His friends all vouched for him being honest and apparently he was genuinely shaken by the sighting. I think he kept drawing and painting the creature because he was trying to figure out what it was.

So if it wasn’t a hoax, and it wasn’t a known or unknown animal, and it probably wasn’t something outside of the realm of science, what’s left? That’s the trouble, we don’t have enough information to know for sure. All we know is that four teenagers saw the creature over the course of about 24 hours, and then it was never seen again.

The more I think about it, the more I come to a single conclusion. If you look in the show notes at the photo I’ve posted of the sad mangy bear, and compare it to Bill’s drawings and painting I also posted, you’ll note some interesting similarities. The body is short, the limbs long in proportion. The legs are shaped the same way in both pictures. There’s no tail. The bear’s head, turned toward the viewer, has the same shape as the Dover demon’s head, it’s just not as large and it has big ears. But Bill didn’t get a good look at the animal, and he saw it briefly in the glare of his headlights on an extremely dark night. He saw the general shape of an animal climbing over rocks, staring into the light with its eyes reflecting the light brightly. Bears do have orange eyeshine and the placement of a bear’s eyes in its face matches what Bill drew.

Here’s what I think happened, maybe. Bill saw a small, thin bear with an advanced case of mange. This meant it had very little hair left and its skin was probably inflamed from scratching. Mange is caused by a mite that burrows under the skin of an animal and causes intense itching. The skin and what was left of the fur would look textured and mottled. The bright eyeshine drew his attention and exaggerated the size of the head in his memory, or it’s possible the poor bear had a swollen face from a bee sting or another malady that made it look much larger than it really was.

John encountered the same bear later that night. It’s not clear from John’s description if the Dover demon was actually walking toward him or just standing in the road. John might not have been able to tell. Bears stand on their hind legs to see better, and the bear was probably alarmed at John’s approach and was trying to decide what to do. When John got too close, the bear ran into the trees, then stopped to look back. That’s when John saw it in silhouette, realized he was seeing something weird, and retreated.

The next evening, the creature was supposedly spotted again by Abby as Will drove her home, and it’s possible that’s what they saw. But by that time Bill had undoubtedly told Will about the bizarre creature he’d seen and shown him his drawing, and Will had undoubtedly told Abby. This could easily have influenced her brief sighting of a goat or other animal, and she thought she had seen the same thing as Bill had. She may even have seen his drawing too. Remember, as I frequently say, people see what they expect to see. We don’t do it on purpose; our brains take what we know of a situation or object or animal and fill in the gaps of what we see so we can make faster decisions about what to do.

I also think John had already seen Bill’s drawing when he made his own drawing, which is why they look so much alike. I just can’t believe that John could have seen the creature’s toes wrapped around rocks at that distance, under the trees, in near-total darkness. I think he was influenced by Bill’s drawing and added the detail without realizing he hadn’t actually seen it. Bill had probably misinterpreted what he saw: namely, the bear’s long claws, which might have looked like part of long fingers, especially if the bear had very little fur on its paws.

My theory certainly doesn’t fit all the facts, primarily the presence of big bear ears which should have been quite noticeable. I did look at a lot of trail cam pictures of bears taken at night, though, and at some angles the bear’s ears don’t show very much or at all. I don’t think my scenario is necessarily what happened, though, just a guess that mostly fits. We would need a lot more information to make a real identification of what creature the teenagers saw that night, and so much time has passed that it’s impossible to get that information now.

So the Dover demon remains a mystery. But even though I’m mostly satisfied that the Dover demon was a sad mangy bear, that has not stopped me from being really jumpy on my usual evening walks. Because I might be totally wrong and I’ll never know.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. Don’t forget to contact me if you want to enter the book giveaway contest, too! Details are on the website, but basically if you want to enter, just contact me any way you like and let me know.

Thanks for listening!