Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:21 — 14.6MB)

Thanks to Connor who suggested this week’s topic, tiger salamanders! Not only do we learn all about the Eastern tiger salamander and the banded tiger salamander, we also learn where asbestos comes from AND IT’S NOT EVEN LIKE I GOT OFF TOPIC, I SWEAR

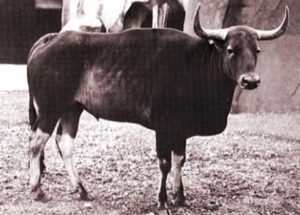

The Eastern tiger salamander:

The barred tiger salamander:

A baby tiger salamander:

A CANNIBAL BABY TIGER SALAMANDER:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’ll learn about an animal suggested by listener Connor that’s been waiting on the ideas list for way too long. Thanks, Connor! Sorry it took me so long to get to your suggestion!

So, Connor suggested that we cover “tiger salamanders’ cannibalism and how salamanders were once believed to be fire-related.” That sentence gives us a lot to unpack.

First let’s find out what a tiger salamander is. It gets its name because it’s stripey, or at least has blotches that can look sort of like stripes. It may be yellow and black or green and black. It grows up to 14 inches long, or 36 cm, which is pretty darn big for a salamander. Smaller tiger salamanders mostly eat insects and worms, but the bigger ones will naturally eat bigger prey, including frogs.

Like all salamanders, the tiger salamander is an amphibian. That means it’s cold-blooded with a low metabolic rate, with delicate skin that needs to stay damp. Like other salamanders, it doesn’t have claws, it does have a tail, and its body is long compared to its short legs. Basically a salamander usually looks like a wet lizard. But salamanders actually have more in common with frogs than with lizards, since frogs are also amphibians.

While the tiger salamander can swim just fine, it spends most of its adult life on land. It catches insects by shooting its sticky tongue at them just like frogs do. And just like a frog, the tiger salamander’s eyes protrude like bumps on its head, and it retracts its eyeballs when it swallows to help force the food down its throat. This is fascinating, but you might want to take a moment to be glad you don’t have to do this every time you swallow a bite of food.

The tiger salamander, like most other amphibians, secretes mucus that helps its skin stay moist and tastes nasty to predators. The tiger salamander doesn’t appear to actually be toxic, though. It mostly lives in burrows it digs near water, and while it’s common throughout much of eastern North America, it’s not seen very often because it’s shy and because it prefers ponds in higher elevations such as mountains.

A female lays her eggs on the leaves of water plants in ponds or other standing water. The eggs hatch into larvae which have external gills and a fin that runs down its back and tail to help it swim. At first the larva looks a little bit like a tadpole, but it grows legs soon after hatching. As a larva, it eats aquatic insects and tiny freshwater crustaceans like amphipods. How soon it metamorphoses into an adult salamander depends on where it lives. Tiger salamanders that live in more northerly areas where summer is short will metamorphose quickly. Tiger salamanders that live in warmer climates stay larvae longer. And in areas where the water is better suited to gathering food than the land is, the larvae may not fully metamorphose at all and will live in the water their whole lives. The term for a fully adult salamander that still retains its external gills and lives in the water is neotene, and it’s pretty common in salamanders of various species.

The tiger salamander is actually closely related to the axolotl, more properly pronounced ash-alotl. I learned that from the Varmints! podcast. Most axolotls are neotenic. On the rare occasion that an axolotl metamorphoses into its adult form, it actually looks a lot like a tiger salamander.

Unfortunately, the tiger salamander carries diseases that can kill frogs, reptiles, fish, and even other amphibians, even though the tiger salamander is usually not affected. The tiger salamander is also a popular pet, but since many pet tiger salamanders were caught in the wild, be careful that you’re not introducing diseases that might kill your other amphibians, reptile, or fish pets. While the tiger salamander is doing just fine in the wild and isn’t protected, it’s always better to buy pets from people who bred the salamanders and can guarantee they’re disease free. Likewise, if you’re someone who likes to fish, don’t use tiger salamander larvae as bait. Researchers think this is the main way the diseases carried by tiger salamanders spread.

So all this information about tiger salamanders is interesting, but it’s also pretty normal for salamanders. What does Connor mean by cannibalism in tiger salamanders?

The tiger salamander we’ve just learned about is actually called the Eastern tiger salamander. Until recently the barred tiger salamander was considered a subspecies of the Eastern tiger salamander, although now it’s considered a separate species. It looks and acts pretty much just like the Eastern tiger salamander but it lives in the western areas of North America. The main difference between the two species is that the barred tiger salamander is not quite as big, and it isn’t as common. The adults are illegal to sell in most American states, although it’s legal to keep them as pets.

But there is one main difference about the barred tiger salamander, and it’s something that only happens in some populations, usually ones in dry areas where ponds are more likely to dry up and larvae need to metamorphose quickly as a result. A few weeks after they hatch, some of the larvae develop large teeth and wider heads. Then they start eating other tiger salamander larvae. Researchers have found that a cannibal tiger salamander won’t eat tiger salamanders it’s related to, and the hypothesis is that it recognizes the scent of its brothers and sisters.

Researchers think most tiger salamanders don’t become cannibals because doing so increases the risk that it will be affected by the diseases tiger salamanders carry. By eating salamanders that are competing for the same resources its siblings need to grow up quickly, the cannibal salamanders help their siblings and may sacrifice themselves by risking disease as a result.

Forget what I said about being glad you don’t have to retract your eyeballs every time you swallow. Just be glad you’re not a tiger salamander at all.

Connor also mentioned the old belief that salamanders lived in fire. How the heck did that belief come about? Salamanders are wet little amphibians that mostly live in water.

It’s been a belief for literally thousands of years. It’s mentioned in the Talmud, in Pliny the Elder’s writings, and in bestiaries. Where did it start?

The main hypothesis is that because some salamanders hibernate in rotting logs, the only time most people would see a salamander would be when they tossed firewood into a fire. The salamander, rudely awakened from its winter home, would slither out of the fire, protected from the heat for a very brief time by its damp skin. There’s actually a species of salamander common throughout Europe called the fire salamander. So that sounds plausible. Older legends refer to the salamander actually being able to put fires out with its cold body or breath. Since salamanders are cold-blooded and damp, they do feel cold to the touch even on relatively warm days.

One traditional writer thought all this was pish-posh, though. Marco Polo himself, who traveled widely in Asia starting in 1271, wrote, “Everybody must be aware that it can be no animal’s nature to live in fire.” He was right, of course. Nothing lives in fire. But by the time Marco Polo lived, there was a certain amount of confusion regarding a type of cloth that was fire-resistant. It was called salamander wool and was supposed to be woven from hairs harvested from salamanders—which is a real trick, considering only mammals have hair.

Marco Polo met a man from Turkey who procured the fibers that were called salamander wool. But they didn’t come from an animal at all. He had to dig for them. I’ll quote from a translation of Marco Polo’s writing:

“He said that the way they got them was by digging in that mountain till they found a certain vein. The substance of this vein was then taken and crushed, and when so treated it divides as it were into fibres of wool, which they set forth to dry. When dry, these fibres were pounded in a great copper mortar, and then washed, so as to remove all the earth and to leave only the fibres like fibres of wool. These were then spun, and made into napkins. When first made these napkins are not very white, but by putting them into the fire for a while they come out as white as snow. And so again whenever they become dirty they are bleached by being put in the fire.

“Now this, and nought else, is the truth about the Salamander, and the people of the country all say the same. Any other account of the matter is fabulous nonsense.”

This actually sounds even more confusing than fire salamanders. What the heck is this cloth, what are those fibers, are they really fireproof, and if so, why hasn’t anyone these days heard of it?

Well, we have, we just don’t realize it. That stuff is called asbestos.

I always thought asbestos was a modern material, but it’s natural, a type of silicate mineral that’s been mined for well over 4,000 years. It’s actually any of six different types of mineral that grow in fibrous crystals. Just like Marco Polo reported, after pounding and cleaning, you’re left with fibers that really are fire, heat, and electricity resistant. As a result, it became more and more common in the late 19th century when it was used in building insulation, electrical insulation, and even mixed with concrete. And just as Marco Polo reported, it was still spun into thread and woven into fabric that was often made into items used around the house, like hot pads for picking up pans from the oven, ironing board covers, and even artificial snow used for Christmas decorations.

Of course, we know now that breathing in bits of silica is really, really bad for the lungs. The dangers of working with asbestos had already started to be known as early as 1899, when asbestos miners started having lung problems and dying young. The more asbestos was studied, the more dangerous doctors realized it was—but since it was so useful, and the effects of asbestos damage on the lungs usually took years and years to manifest, businesses continued to ignore the warnings. Asbestos was even used in cigarette filters during the 1950s, as if smoking wasn’t already bad enough.

These days, most uses of asbestos have been banned around the world, but if you’ve seen those TV commercials asking if you or someone you know suffers from mesothelioma, and you might be entitled to compensation, that’s a disease caused by breathing in asbestos dust. Some industries still use asbestos.

It sounds like asbestos being called salamander wool was named not because people literally thought they were made from hairs harvested from salamanders but because asbestos cloth resisted fire and heat the way salamanders were supposed to. These days chefs use a really hot grill called a salamander to sear meats and other foods, which is named after the folkloric animal, but no one believes it has anything to do with real salamanders. At least, I hope not. Then again, there are pictures of salamanders in medieval bestiaries showing salamanders with hair, which argues that at least some people really truly believed that asbestos came from salamanders.

Because tiger salamanders are large and not endangered, they’re good subjects for study. Researchers have learned some surprising things by studying the behavior and physiology of tiger salamanders. For instance, salamanders in general have legs that haven’t changed that much from those of the first four-legged animals, or tetrapods. Researchers study the way tiger salamanders walk to learn more about how early tetrapods evolved. And yes, this research did involve filming tiger salamanders walking on a tiny treadmill.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!