Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:16 — 16.7MB)

This week we’re looking at some strange and mysterious canids from around the world!

The African wild dog:

A dhole:

An old photo of the ringdocus and a newer photo of the ringdocus:

A coyote:

Sri Lankan golden jackal:

The maned wolf MONEY SHOT:

A bush dog:

A stuffed Honshu wolf, dramatically lit:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s look at a bunch of mystery doggos from around the world! I really like dogs, but for some reason dogs and their relations don’t come up much on the podcast. When I started looking into mystery canids, though, I found so much information that there’s no way I can stuff even half of it into one episode. So we’ll definitely be revisiting mystery dogs in the future.

The family Canidae includes dogs, wolves, coyotes, jackals, and foxes. Yes, foxes are canids, but not closely related to more dog-like canids. We’re going to skip the foxes this week, since foxes deserve an episode all their own eventually.

Dogs were domesticated at least 9,500 years ago, possibly as long as 14,700 years ago, maybe even as long as 36,000 years ago. Dogs and humans go way back. The closest living relative of the dog is the gray wolf, which is still alive today, but the wild ancestor of the domestic dog was a different species of wolf that has gone extinct.

There are canids called wild dogs, but they’re not the same species as domestic dogs. The African wild dog, for instance, is not very closely related to dogs and wolves—in fact, it’s the only species in its own genus. It’s a tall, lean canid with large ears and no dewclaws. It has a yellowish coat with black blotches and some white spots, including a white tail tip, although some subspecies have darker coats. As the dog ages, it loses its fur until old dogs are nearly bald. It hunts in packs and mostly preys on antelopes, warthogs, ostriches, hares, and rodents.

The nomadic Tuareg people who live in northern parts of Africa around the Sahara have stories of a supernatural creature called the Adjule, among other names. The Adjule’s description makes it sound a lot like the African wild dog, including its lack of a dew claw. Since the African wild dog is rare in that part of Africa, it’s possible that rare sightings of what is a distinctively odd-looking animal may have given rise to the stories.

Another so-called wild dog is the dhole, also called the Indian wild dog, which is closely related to the African wild dog. It used to be common throughout Eurasia and North America, but these days it’s restricted to parts of Asia and is endangered. It looks something like a fox and something like a wolf, but is neither. Like many other canids in this episode, the dhole has its own genus. Because it tends to be easily tamed and is sometimes kept as a pet, researchers once believed domestic dogs might have descended from the dhole or an ancestral species of dhole, but genetic evidence shows that the dhole isn’t closely related to domestic dogs or to wolves.

There are three subspecies of dhole, two of them reddish-brown in color and one with fur that’s pale brown in winter. But there is a mystery animal called the gray dhole that may turn out to be a fourth subspecies or something else.

The gray dhole supposedly lives in the forests and mountains of Myanmar. It’s dark gray with a black muzzle and small, round ears, and is supposed to be smaller than the other dhole species. In 1913 a Major E.G. Phythian-Adams wrote about the grey dhole after he saw one that year, and in 1933 E.H. Peacock mentioned it in his book A Game Book for Bhurma and Adjoining Territories. In 1936 an explorer named Tsaing reported seeing one in Burma. But after these reports, the Bombay Natural History Society tried to find physical evidence of the animal in the 1950s, but couldn’t track down anything. They only found one person who even reported seeing the grey dhole. So even if it is a separate species or subspecies and not just a rare color morph of a known species of dhole, it’s probably extinct now.

Kipling wrote about the dhole in one of his Jungle Book stories, calling it the red whistling dog of the Deccan, and reporting that packs of the animals were so ferocious that even tigers would avoid them. This is true, even the whistling part. Instead of barking or howling, dhole calls are whistles. This is what a dhole sounds like:

[dhole sound]

In 1886 a Montana settler named Israel Hutchins shot a wolflike animal that had reportedly been killing livestock. No one knew what it was, so Hutchins traded it to a taxidermist for a cow. He needed the cow because when he first tried to shoot the canid, he accidentally shot one of his own cows instead. The taxidermist, Joseph Sherwood, also owned a general store in Idaho. He displayed the stuffed canid in the store, where it stayed for almost a hundred years until it disappeared. In 2007 Hutchins’s grandson, Jack Kirby, traced it to the Idaho Museum of Natural History.

The stuffed mystery canid is usually called the ringdocus, a name Sherwood made up. It has a sloping back and some other un-wolf-like features that might be due to bad taxidermy or might be due to physical anomalies in an ordinary wolf—or might be due to the ringdocus being an animal new to science. Suggestions as to what it might be include a thylacine, a hyena, a wolf-coyote hybrid, a wolf-dog hybrid, or a dire wolf. It’s not a thylacine, just going to say that straight out. Since we have the taxidermied specimen, it seems logical that a DNA test would clear up the mystery or bring us a brand new scientific mystery, if it turns out to be an unknown animal. But Kirby doesn’t want a DNA test done. That tells me it’s probably just a wolf, and he knows it’s a wolf. Prove me wrong, Kirby. I bet you ten whole dollars it’s just a wolf.

Around the same time that Hutchens was shooting at the ringdocus and killing his cow, and probably saying some very bad words when it happened, a man called Payze bought what he thought was a fox cub from some men traveling to London. It was 1883 and the men had caught the cub, along with two others, in Epping Forest. Payze named the cub Charlie, but as Charlie grew up, he started looking less and less like a fox. Payze took him to London Zoo and showed him to the superintendent, who identified him as a coyote.

But how had a coyote gotten to England? Coyotes are native to North America. The coyote is smaller than a wolf, usually a bit bigger than a fox but with longer legs, and can look fox-like. It’s gray and brown, or sometimes reddish, with large ears and a brushy tail.

It turns out that four coyotes had been brought to England and released near Epping Forest not long before, presumably for hunting. Clearly they’d had at least one litter of pups, but is it possible they survived and had more offspring? Locals do occasionally report seeing wolves or gray foxes in the area. Since coyotes readily breed with dogs and produce fertile offspring, it’s possible that some local dogs have coyote in their ancestry.

The Sri Lankan golden jackal lives in Sri Lanka and parts of India. It’s a small canid, with grizzled black and white fur above and tan or golden on the belly and legs. It’s a subspecies of the golden jackal, and it’s sometimes called the horned jackal. Local people in Sri Lanka believe that the leader of the pack has a small horn on the back of its skull, although other people report the horn is on its forehead. The horn is supposed to have supernatural powers and is considered a valuable talisman or charm.

That sounds nutty, but we actually have golden jackal skulls with small pointy horns less than an inch long, or a few centimeters. So the horns are real, but they’re not actual horns. They’re most likely bony growths resulting from an injury to the skull. No one’s sure why golden jackals grow them but not other canids.

The Falkland Islands is an archipelago about 300 miles, or 480 km, off the coast of Patagonia at the southern end of South America. When European explorers first discovered the islands in the late 17th century, no people lived there, just lots of birds and a fox-like wolf. Charles Darwin saw it in 1834 and described it as a wolf-like fox, but modern DNA research shows that it’s not only not a fox, its closest living relative is the maned wolf, which still lives in parts of South America.

The Falkland Islands wolf was tawny in color with a white tip to its tail. It had relatively short legs but was a fairly large animal, standing about two feet tall at the shoulder, or 60 cm. Its fur was thick and it barked like a dog. It may have lived in burrows. Because no mammals except the wolf lived on the Falkland Islands until settlers arrived, the wolf probably mostly ate seabirds, insects, and anything it could scavenge from the seashore.

For a long time it was a mystery how the Falkland Islands wolf got to the islands. There were no other wild canids in Patagonia, and the islands were never connected to the mainland. The islands aren’t even visible from the mainland. But the Falkland Islands wolf used to have a close relative that lived in Patagonia and other parts of South America. Dusicyon avus was about the size of German shepherd, and may have been at least partially domesticated. The grave of a young D. avus was found among human graves dating to over 2,000 years ago in Argentina. Estimates of when D. avus went extinct vary from 1,000 BCE to only around 300 years ago. Either way, researchers think that about 16,000 years ago, during the last ice age, the sea level was lower and only a shallow strait separated the mainland from the Falkland Islands. At times the strait may have frozen over, allowing animals to travel to the islands. When the glaciers melted and the sea level rose, some of the wolves were trapped on the islands. They evolved over the centuries to better fit their island habitat.

The Falkland Islands wolf wasn’t afraid of humans since it had no predators. That meant that sailors and other people who visited the islands could kill the wolves easily. It was hunted for its fur, or sometimes just poisoned by settlers who believed it killed sheep. It went extinct in 1876.

So what about the maned wolf, the Falkland Islands wolf’s living relation? It is a very weird animal, and in fact you’ll often see it listed in articles about the weirdest animals ever.

The maned wolf resembles a fox in many ways. It has reddish fur with black legs and muzzle and a black mane along its spine, a white tip to its tail, and a white patch on its throat. Its ears are big and its muzzle relatively short. Oh, and its legs are long. Really, really long. Super long. At first glance, it almost looks like a deer.

The maned wolf’s body is about the size of a good-sized dog’s, but its legs are far longer than any dog’s legs. Researchers think the maned wolf evolved longer legs to better see over the tall grasses where it lives. It’s a solitary animal and hunts small animals and birds, but about half its diet is plants. It especially likes a tomato-like fruit called the wolf apple. It marks its territory with a stinky musk that smells enough like cannabis that at least one zoo security team has mistaken it for people smoking marijuana.

Not only is the maned wolf not a wolf, it’s not a fox either. It’s not really closely related to any other living canids. It is, in fact, its own thing, the only living canid in its genus. While it’s related to the Falkland Islands wolf, its closest living relative is the bush dog, also the only species in its genus, also an odd canid from South America. But while the maned wolf is very tall, the bush dog is very short, only about a foot tall at the shoulder, or 30 cm.

The bush dog has plush brown fur that’s lighter on the back and darker on the belly, legs, and rump. Its ears are small, its snout short, and its tail is relatively short. It actually looks more like an otter or big weasel than a dog. It sometimes hunts in packs, sometimes alone. When it hunts alone it mostly eats small rodents, lizards and snakes, and birds, but packs can kill larger animals like peccaries, a type of wild pig. It lives in extended family groups and hunts during the day.

The bush dog is rare and not much is known about it. Its toes are webbed and it spends a lot of time in the water within its forest habitat. It’s so rare that for a long time it was only known from fossils found in some caves in Brazil, and was thought extinct.

Conversely, the Japanese wolf, or Honshu wolf, is a canid that is supposed to have gone extinct in January of 1905 when the last known wolf was killed. But people keep seeing and hearing it in the mountains of Japan.

The Honshu wolf was also small, not much more than a foot tall at the shoulder, or 30-odd cm, but it was a subspecies of gray wolf. Its legs were short and its short coat was greyish-brown. It was once considered a friend to farmers, since it ate rats and other pests. Wolves were also regarded as protective of travelers in Japanese folklore. But in 1732 rabies was introduced to Japan. That disease combined with loss of habitat made the Honshu wolf more of a threat to humans and their livestock, and led to its persecution.

But sightings of the wolf have continued ever since that last one was killed in 1905. Photographs of a canid killed in 1910 were studied by a team of researchers in 2000, who determined that the animal in the photos was probably a Honshu wolf. People have found tracks, heard howling, seen wolf-like animals, even taken photos of what look like wolves. The problem is that the Japanese wolf looked similar in many ways to some Japanese dog breeds like the Shiba inu and the Akita, which are probably partly wolf anyway since wolves and dogs interbreed easily and produce fertile offspring. People might be seeing dogs roaming the countryside. We can’t even DNA test hairs and old pelts to see if they’re from wolves, because we don’t have a genetic profile of the Honshu wolf. There are only a few taxidermied specimens of the wolf, and none of them have yielded intact DNA.

Another mystery not definitely solved by DNA testing, although at least they’ve tried, is the Andean wolf, sometimes called Hagenbeck’s wolf. It’s another South American mystery canid. In 1927, a German animal collector called Lorenz Hagenbeck bought a wolf pelt in Buenos Aires. The seller said the pelt, and three others, came from a wolf-like wild dog in the Andes Mountains.

The pelt is about six feet long, or 1.8 meters, including the tail, with thick, long fur, especially a thick ruff on the neck. It’s black on the back and dark brown elsewhere.

Hagenbeck didn’t recognize the pelt, so when he got home he sent it for examination. In the 1930s and 1940s, various studies suggested it belonged to a new species of canid, possibly one related to the maned wolf. One mammologist, Ingo Krumbiegel, also thought he might have seen a skull of the same canid in 1935, which he said had resembled a maned wolf skull but was much larger, and was supposed to have come from the Andes. Krumbiegel was convinced enough that in 1949 he described the Andean wolf formally as a new species. But no more specimens have come to light.

In 1954 another study determined Hagenbeck’s pelt was just a dog pelt, possibly of a German Shepherd crossbreed. A 1957 study came to the same conclusion. In 2000, a DNA analysis came back inconclusive due to the pelt having been chemically treated during preparation, and contamination with dog, wolf, human, and pig DNA. Currently the pelt is on display at the Zoological State Museum in Munich.

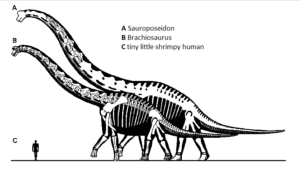

Finally, the dire wolf is a famous canid from books, games, and movies, but it was also a real animal. It lived throughout North and South America and was bigger than modern gray wolves, standing over three feet tall at the shoulder, or about 97 cm. It had massive teeth and powerful jaws that would have helped it kill giant ground sloths, mastodons, bison, horses, and other ice age megafauna. It wasn’t as fast a runner as modern wolves, though, and some researchers think the gray wolf may have outcompeted the dire wolf.

The dire wolf probably died out about 9,500 years ago, but there’s a group called the Dire Wolf Project that’s attempting to breed a dog that looks like a dire wolf. The group isn’t introducing any modern wolf genes into the breed, though, since they want a dog that looks like a dire wolf but doesn’t act like one. Which is pretty smart considering that dire wolves probably snacked on our own ancestors from time to time.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!