Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:36 — 15.3MB)

Thanks to Liesbet, Simon, and Thea for their suggestions this week! Let’s learn about some birds!

Further reading:

Blue Tits and Milk Bottle Tops

Ravens parallel great apes in flexible planning for tool-use and bartering

Further watching:

A Raven Calling [this is a great video of a raven making all sorts of interesting sounds–I only used a tiny clip of it in the episode but it’s worth watching the whole thing]

The European robin:

The American robin and a worm that is having a very bad day:

A blue tit [photo By © Francis C. Franklin / CC-BY-SA-3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37675470]:

A blue tit about to get the cap off that milk bottle [photo from link above]:

The Eastern bluebird:

A raven:

An American crow:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have suggestions from Liesbet, Simon, and Thea, who suggested some relatively common birds that you may already think you know all about, but there’s lots to learn about them!

We’ll start with Liesbet’s suggestion, about the European robin and bluebird, and while we’re at it we’ll learn about the American robin and bluebird. The European and American birds are completely different species. The reason they have the same names is because when Europeans first started paying attention to the birds of North America, they needed names for the birds. The native peoples had names for them, of course, but the Europeans wanted names in a language they understood, so in a lot of cases they just borrowed names already in use at home.

Let’s start with the robin, which we also talked about way back in episode 81.

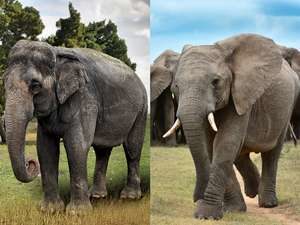

The European robin is a little bitty bird, only around 5 inches long, or 13 cm, with a brown back, streaked gray or buff belly, and orange face and breast. It has a short black bill and round black eyes. It eats insects, worms, berries, and seeds. The eggs are pale brown with reddish speckles.

It lives throughout much of Eurasia, but robins in Britain tend to be fairly tame, probably because they were traditionally considered beneficial in Britain and Ireland, so farmers and gardeners wouldn’t hurt them. In other parts of Europe they were hunted and are much more shy. European robins are also common on Christmas cards in Britain and Ireland, possibly because in the olden days, postmen used to wear red jackets. The postmen started to be called robins as a result, and since postmen bring Christmas cards, the bird robin became linked with card delivery and finally just ended up on the Christmas cards. Plus, their orange markings are cheerful in winter.

This is what the European robin sounds like:

[robin song]

The American robin is a type of thrush. It lives year-round in most of the United States and parts of Mexico, spends summers in much of Canada, and winters in parts of Mexico. It’s very different from the European robin. The European robin is tiny and round and adorable, while the American robin is big and always looks kind of angry. It grows around 10 inches long, or 25 cm. It’s dark gray on its back, with a rusty red breast, white undertail coverts, and a long yellow bill. It also has white markings around its eyes. Young birds are speckled. It mostly eats insects, worms, and berries.

If you see a bird on the ground, running quickly and then stopping, it’s probably a robin. Mostly the robin hunts bugs by sight, but it has good hearing and can actually hear worms moving around underground. You can sometimes see a robin with its head cocked, listening for a worm, before pouncing and pulling it out of the ground, just like in a cartoon.

American robin eggs are a light teal blue, so common and well-known that robin’s-egg-blue is a typical description of that particular color. In the spring after eggs hatch, the mother robin will carry the eggshells away from the nest to drop them, so predators won’t see the shells and know there’s a nest nearby. That’s why you’ll sometimes see half a robin eggshell on the sidewalk. It doesn’t mean something bad happened to the baby, just that the mother bird is doing her job. Both parents feed the chicks, and the parents also carry off the babies’ droppings to scatter them away from the nest.

This is what an American robin’s song sounds like.

[robin song]

Liesbet also wanted to learn about the European bluebird, more commonly called the Eurasian blue tit. We haven’t talked about it or the American bluebird before, even though they’re both beautiful birds.

The blue tit lives throughout Europe and parts of western Asia. It grows around 4 and a half inches long, or 12 cm, and has a bright blue crown on its head with blue on its wings, tail, and back. Its face is mostly white but it has a black streak that crosses its eye and a black ring around its neck. In fact, if you’re familiar with the blue jay of North America, the blue tit looks a lot like a miniature blue jay. It even has a little bit of a crest that it can raise and lower.

Because it eats a lot of insects and other small invertebrates, along with some seeds, the blue tit is an acrobatic bird. It will hang upside down from a twig to reach a caterpillar on the underside of a leaf, that sort of thing. It will also peel bits of bark away from a tree trunk to find tiny insects and spiders hiding underneath it. This habit leads it to sometimes peel bits off of people’s houses, like the putty that holds windowpanes in place. It also once led to the blue tit learning a surprising way to find food, and to learn about that, we have to learn a little bit about how people in the olden days got their milk if they didn’t own cows.

Back in the early 20th century, people used to get milk delivered every morning by a milkman. Refrigerators and ice boxes weren’t common like they are today, and most people didn’t have a way to keep milk cold. That meant it would go bad very quickly, so people would just order how much milk they needed in one day and when they got up in the morning, the milkman would have left the milk and other dairy products on the doorstep for the family.

The milk was always whole milk, also called full-fat, and as it sat in its bottles on the doorstep waiting for the family to wake up and bring the milk in, the cream would separate and rise to the top of the milk. Cream is just the fattiest, richest part of the milk. These days milk is processed differently so even if you buy whole milk, the cream won’t separate from it, and most milk sold today has already had most of the cream separated out. That’s why skim milk is called that, because the cream has been skimmed off the top. It’s sold separately as heavy whipping cream or mixed with milk as half-and-half. But back in the olden days, if you wanted to make whipped cream or clotted cream or some other recipe that calls for cream, you’d just skim the cream off yourself to use it.

The problem is, cream is so rich and full of protein that other animals learned to rob milk bottles, especially the blue tit. Birds can’t digest milk, naturally, since only mammals produce milk and are adapted to digest it, and even most adult mammals have trouble digesting milk. But cream contains a lot less lactose than the milk itself, and lactose is the type of sugar in milk that can cause stomach upset in adults. Blue tits learned that if they peeled the little foil cap off a milk bottle, they could get at the cream, and it became such a widespread behavior that each generation of blue tits became more adapted to digest cream.

These days, of course, most people buy their milk at the grocery store. The blue tits have had to go back to eating bugs and seeds.

This is what a blue tit sounds like:

[blue tit song]

The bluebird is a North American bird that also eats insects and other small invertebrates, along with berries and seeds. It grows around 7 inches long, or 18 cm. There are three species, the eastern bluebird and western bluebird, which look similar with bright blue above and white underneath with rusty red breast, and the mountain bluebird, which is blue almost all over and lives in mountainous areas of western North America. The bluebird is a type of thrush, meaning that it’s actually related to the American robin and used to be called the blue robin.

The bluebird spends a lot of its time sitting on a branch and watching for insects in the grass below. When it spots a grasshopper or beetle or spider or even a snail, it will drop down from its branch to grab it. It prefers open grasslands with trees or brush it can perch in, so it’s common around farmland. The mountain bluebird hunts like this too, but it doesn’t always bother to perch and will just hover above the ground until it spots a bug.

This is what an eastern bluebird sounds like:

[bluebird song]

Next, Simon and Thea wanted to learn about crows and ravens. The raven is another bird we covered a long time ago, in episode 112. I had a really bad cold the week of that episode and not only did I sound awful, I didn’t do a very good job with my research. I’m glad to revisit the topic and correct a few mistakes.

Crows and ravens look similar and are closely related, with both belonging to the genus Corvus. There are lots of species and subspecies of both, but let’s talk specifically about the American crow since it’s closely related to the hooded crow and the carrion crow found throughout Europe and Asia. Likewise, we’ll talk about the common raven since it’s found throughout much of the northern hemisphere.

The American crow can grow up to about 20 inches long, or 50 cm, with a wingspan over 3 feet across, or about a meter. Meanwhile, the common raven has a wingspan of up to 5 feet across, or 1.5 meters, and can grow up to 26 inches long, or 67 cm. Both are glossy black all over with large, heavy bills and long legs.

Crows and ravens both mate for life. Crows in particular are devoted family birds, with the grown young of a pair often staying to help their parents raise the next nest.

Both crows and ravens are omnivores, which means they eat pretty much anything. They will eat roadkill and other carrion, fruit and grain, insects, small animals, other birds, and eggs. They’re also extremely smart, which means a crow or raven can figure out how to get into trash cans and other containers to find food that humans think is secure.

Both also sometimes make and use tools, especially sticks that they use to dig out insects in places where their beaks can’t reach. But ravens in particular show a lot of tool use. Ravens sometimes throw pinecones or rocks at people who approach too close to their nests, and will even use sticks to stab at attacking owls. A few ravens have been observed to hold big pieces of bark in their feet while flying in strong winds, and they use the bark as a sort of rudder to help them maneuver. Other cognitive studies of ravens show that they have sophisticated and flexible problem-solving abilities where they can plan at least one step ahead, similar to great apes. Other corvids show similar abilities.

The raven can imitate other animals and birds, even machinery, in addition to making all sorts of calls. It can even imitate human speech. If a raven finds a dead animal but isn’t strong enough to open the carcass to get at the meat, it may imitate a wolf or fox to attract the animal to the carcass. The wolf or fox will open the carcass, and even after it eats as much as it wants, there’s plenty left for the raven.

Ravens also communicate non-vocally with other ravens. A raven will use its beak to point with, the way humans will point with a finger. They’ll also hold something and wave it to get another raven’s attention, which hasn’t been observed in any other animal besides apes.

The raven is much larger and heavier than a crow, and you can also distinguish a crow from a raven by their calls. This is what an American crow sounds like:

[crow call]

And this is what a raven sounds like:

[raven call]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!