Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:53 — 34.7MB)

Subscribe: | More

Here it is, our 300th episode! Which just happens to fall on Halloween! We have a spooooooky episode for sure this time, a full five out of five ghosts on our spookiness scale. Beware!!

Don’t forget to order your copy of Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie, available wherever you buy books!

Check out the great podcast Bring Birds Back. They were kind enough to run a promo for us in the middle of their Halloween episode so I’ve returned the favor.

Further reading:

‘Loveland Frogman’ Spotted Again?

The Loveland Frogman Is Back!!! Beware.

Officer who shot ‘Loveland Frogman’ in 1972 says story is a hoax

Close Encounter at Kelly (PDF)

A picture from the 2016 sighting:

“Jim” the frogman cosplayer (from the second article linked to above):

The 27 March 1972 Cincinnati Post article, titled “Loveland monster” by Si Cornell (p.7):

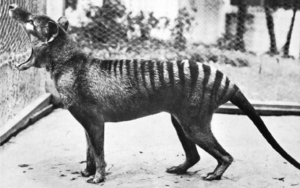

A really big iguana:

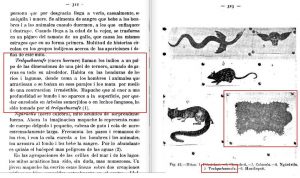

The 1955 sighting, drawn in 1956 by the witness’s interviewer:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s finally Halloween, and it’s also our 300th episode! Wow! I don’t think I’ve ever made 300 of anything before. To celebrate, this episode is going to be our most Halloween-y yet, a solid five out of five ghosts on our spookiness scale. Beware, muahahaha!

As usual in our Halloween episodes, we have a little bit of housekeeping before we start. The Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie book is still available everywhere you order books. I have six or seven copies of the paperback if you want to buy a signed copy directly from me. Just drop me an email if you’re interested.

This past year has been extremely busy for me. Apart from the podcast, I also sold my house and moved to an apartment, went to a lot of conventions to sell books, and worked on my fiction writing. I self-published a novella this summer called Royal Red, which is about dragons, but it’s not appropriate for younger readers so I won’t link to it. Everything I’ve done this year has been positive ultimately, but it was incredibly stressful at the time. Now that things are settling down, I’ve had time to think about what I want to do in the future.

I love making Strange Animals Podcast, but it’s also taking up more and more of my time. I have a lot of hobbies and interests outside of podcasting, which I haven’t had time to do very much in the last few years. I need to pull back and regain time for myself. But don’t worry, we’ll still have an episode every week! The episodes will just be shorter on average. Hopefully you won’t even notice the change.

Feel free to continue sending in your suggestions and feedback. I know I’m really backed up on suggestions and hope to get to a bunch of them in the next few months. If you worry that I never got your suggestion, you can send it again! Also, if you want a sticker, send me your mailing address and I’ll mail you one. That’s true all the time, not just right now.

Thanks to everyone for supporting the podcast over the last 300 episodes! Let’s aim for another 300. Also, stick around to the very end of the episode to hear a promo from a great podcast called Bring Birds Back. I think you’ll really like the show.

Now, it’s time to learn about the LOVELAND FROG. Which does not sound spooky, but believe me, it is.

The story doesn’t start in 2016, but that’s where we’re going to start. In early August 2016, a young man named Sam Jacobs was playing Pokemon Go with his girlfriend in Loveland, Ohio. They were near Lake Isabella when Sam noticed a big frog in the water. It was getting dark at this point and all Sam could see was the frog’s eyes reflecting light and its head and back above the water. It was so big that he took pictures and even video, but then the frog stood up out of the water and walked around on its hind legs, the size of a human.

But that wasn’t the first time someone had seen a giant frog-man in the area. In 1972 it was seen twice, both times by policemen.

On March 3, 1972, a policeman named Ray Shockey was driving along Riverside Road at about one in the morning. This was just outside Loveland, Ohio, and as the road’s name implies, the road followed along the Little Miami River. Officer Shockey saw what he initially thought was a dog in the road, but as he came closer, the animal stood up on its hind legs. He said it was about four feet tall, or 1.2 meters, with a face that looked like a frog’s or a lizard’s. Its skin looked leathery but textured. The creature stared at the car for a moment, then jumped over a guard rail and down toward the river.

Shockey was shocked, naturally, and hurried to the station. He told another officer on duty about what he’d seen, Mark Matthews, and the two returned to the spot where Shockey had encountered the creature. They found what looked like scrape marks on the ground leading down to the river, but nothing else.

A few weeks later, Mark Matthews saw the creature himself. He was driving along the river when he saw what he thought was a dead animal on the road. He stopped to move it off the road when it sat up, hurried to the guard rail and climbed over it. Officer Matthews shot at the creature but either missed, or the animal wasn’t hurt badly enough to stop.

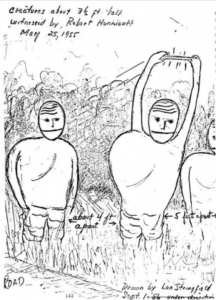

But this still isn’t the first time the creature was sighted. We have to go back to 1955 for the first sighting of the creature now known as the Loveland frog or the Loveland frogman. There are various versions of the story but in general, in May of 1955, a businessman named Robert Hunnicott was driving along the Little Miami River at about 3:30 in the morning and saw three strange creatures standing on their hind legs. He was so shocked that he stopped his car to get a better look.

The creatures were no more than 4 feet tall, or 1.2 meters, and had gray leathery skin and faces like frogs. Instead of hair, the skin on their heads was deeply wrinkled. He also noticed they had webbed hands and feet. As Hunnicott stared, one of the figures raised a wand over its head and sparks shot out of it. At this point Hunnicott decided it was time to go, and he drove away quickly.

So, you have to admit, this is a truly spooky event. It may be the spookiest thing we’ve ever discussed on this podcast. But things aren’t all that they seem, so let’s revisit all three stories and learn a little more.

If you read the Wikipedia entry for the Loveland frog, at least as of late October 2022, under the “Popular culture” heading it discusses the 2016 sighting and finishes “It was later revealed to be a local student from Archbishop Moeller High School in a homemade frog costume.” This statement cites as its source a November 13, 2020 article written by a student for the Moeller Crusader, the high school’s newspaper.

But if you actually read the article, which I’ve linked to in the show notes, you’ll notice that it’s meant to be funny. For instance, this paragraph, which purports to be a quote from a student called Jim:

“‘I’ve been obsessed with the Loveland frog since I was a little boy,’ said Jim. ‘He’s like my idol. I dress up as him and go to the tunnel and hop around a few times a week. I sometimes make little chocolates shaped as flies and I’ll eat them while I hop around. And no, I don’t think it’s weird.’”

This actually made me laugh. But nowhere in the article does it state that “Jim” was in the lake in 2016 while Sam Jacobs and his girlfriend were playing Pokemon Go. If Jim was an Archbishop Moeller High School student in November 2020 when the article was published, he would not have been a high school student in August 2016 unless he had to stay in high school for five years instead of the usual four. Either that or he started wearing his costume around in middle school but was only seen once until the article ran in 2020. Also, in the pictures accompanying the article, the frog costume is just an oversized head made of plush fur, not the sort of thing you’d want to wear into a lake and not matching the size of the creature photographed in 2016. Anyway, as I said, the article is clearly meant to be funny, not factual.

In other words, while Wikipedia is a perfectly good source of general knowledge on a topic, make sure you double-check the references cited for accuracy, and don’t use Wikipedia as your only source.

All that aside, it’s a good possibility that the 2016 sighting was a hoax. The pictures and video are grainy since it was dark out, so basically all you can see is what seems to be a dark green or gray human-like figure standing in the water about waist-deep. The glow of its eyes is so bright they look like LED lights instead of the normal eyeshine of a nocturnal or crepuscular animal. The lights also appear to be white. White eyeshine is generally only found in fish, while frogs generally have green eyeshine. Of course, the Loveland frog isn’t actually a frog, and if it is something new to science it could potentially have any color of eyeshine. But such bright white eyeshine is more likely to be due to an artificial light source causing the glow, not the reflection of light.

Let’s go back to the 1972 sightings next. The initial sighting made by Ray Shockey happened in early March. Loveland is a community on the outskirts of Cincinnati, Ohio, and according to online weather history archives, the temperature dipped down to 24 degrees Fahrenheit that night, or -4 Celsius. The following day, Saturday, the temperature only reached 39 F, or 4 C.

It was also windy, which would make it feel even colder.

The Cincinnati Post newspaper reported on the sighting in a March 27, 1972 article. The article takes a humorous tone but it does have some solid reporting, so I’m going to quote a lot of it.

“Patrolman Ray Shockey, 23, was cruising along the river late at night when he saw ‘an animal two to three feet tall with dark green or blackish scaly skin.’ The thing ducked over the bank into the river.

“Ten days ago, Patrolman Mark Matthews, 21, was driving home from duty along the same road at 6 a.m. Near Loveland’s city limits, a good quarter mile from the first sighting but still close to the river, he saw ‘the same type of creature’ and was able to partially swing his headlights on it.

“Matthews said the irritated monster ‘stuck its tongue out at me…it was forked like a serpent’s.’ He fired three shots, apparently missing, and the monster skedaddled towards the water. He estimated the thing as two to four feet high.”

Now we have some real details! The article ends with a quote from a local zookeeper, who noted that the sketch the two officers had made from their reports resembled The Creature from the Black Lagoon, a monster movie that had only been released the year before.

The forked tongue is a telling detail, because there’s a particular animal that mostly fits the creature’s description that does have a noticeable forked tongue. That’s the monitor lizard, and we’ve talked about various monitors in lots of past episodes. Monitor lizards are popular pets in the United States and can easily grow three or four feet long, or 91 to 122 cm. The monitor’s snout is relatively blunt and can look frog-like, although it’s at the end of a relatively long neck. It also has a long tail, so while some details fit the sightings, it’s not a perfect match.

Besides, the monitor lizard is a reptile, and therefore cold-blooded, or ectothermic, meaning its internal body temperature depends on the temperature outside. It can’t function well in cold temperatures and will die if it gets too cold. The same is true of frogs and other amphibians, for that matter, many of which hibernate in burrows, crevices in rocks or logs, and other places protected from freezing temperatures.

It was warmer when Matthews spotted the creature on March 17, 1972, although still not much above freezing. The high temperature that day was 48 F, or almost 9 C, but at 6am it was probably colder. That’s still really cold for a reptile or amphibian to be out and about in the dark.

But that’s not all, because in 2016, after Sam Jacobs and his girlfriend saw the Loveland frog, Mark Matthews contacted the Cincinnati news station WCPO and his story had changed a lot in the 44 years since his own sighting. Even the spelling of his name had changed, with Matthews spelled with one T instead of two, but the 2-T spelling might have been a mistake in the original reports from 1972.

In his 2016 interview, Matthews now said he “was driving on Kemper Road near the boot factory when he saw something run across the road. However, it wasn’t walking upright and didn’t climb over the guardrail as the urban legend of the Frogman goes. The creature crawled under the guardrail. […] ‘I know no one would believe me, so I shot it,’ he said.

“Mathews recovered the creature’s body and put it in his trunk to show Shockey. He said Shockey said it was the creature he had seen, too. It was a large iguana about 3 or 3.5 feet long, Mathews said. The animal was missing its tail, which is why he didn’t immediately recognize it.

“Mathews said he figured the iguana had been someone’s pet and then either got loose or was released when it grew too large. He also theorized that the cold-blooded animal had been living near the pipes that released water that was used for cooling the ovens in the boot factory as a way to stay warm in the cold March weather.”

A big male iguana can get quite large, up to 6 feet long including the tail, or 1.8 meters, and they’re also popular pets. The iguana has a shorter neck than a monitor lizard and a blunt muzzle that could be considered froglike. However, it also has a long tail, a dewlap under the throat, and a row of little spikes down the spine. All these details are distinctive and not reported in the initial reports. It does have a forked tongue, but it’s not noticeable unless you get a good look at it from up close. If Matthews had killed the animal and examined it, he might have seen the tongue and gave that detail to a reporter in 1972, but why didn’t he also mention the spikes and dewlap? If he was trying to protect his fellow officer from ridicule by backing up his story, he didn’t need to stick to details he really saw. He could have made up anything, but instead he just said that the animal stuck a forked tongue at him and ran toward the water.

Besides, it seems awfully convenient that Mark Matthews’s iguana was missing a tail, which would have made it look more froglike, and was active on two nights, one of them below freezing. Iguanas are not nocturnal. It’s also convenient that although he supposedly had the dead animal in his patrol car, he didn’t take any pictures or show anyone except Shockey, who had already died by the time Matthews made his 2016 claim. I don’t think Mark Matthews killed an iguana or anything else that night.

One suggestion is that the animal might have been a mammal with a bad case of mange, which made its skin look like textured leather and made it hard to recognize. But with so few concrete details, no physical evidence, and a witness who changed his story considerably, we can’t even make a guess.

Finally, going back to the 1955 sighting is even more difficult. The best documentation of what happened appears in a publication called Close Encounter at Kelly and Others of 1955, published in 1978 by the Center for UFO Studies. The bulk of the publication is concerned with what’s now called the Kelly-Hopkinsville encounter that happened in Kentucky. I won’t get into the details here because it could and probably one day will be an episode all to itself, but it happened in late August 1955. Part two of Close Encounter at Kelly talks about other strange occurrences that happened not too far away or too long before or after the Kelly-Hopkinsville encounter. According to that publication, the story originally appeared in a September 2, 1955 zine called the CRIFO Orbit, where CRIFO stands for “Civilian Research, Interplanetary Flying Objects.” The editor, Leonard Stringfield, recounts the original article:

“…We should like to cite a case involving a prominent businessman, living in Loveland. Occurring several weeks ago, this person…saw four ‘strange little men about three feet tall’ under a certain bridge. He reported the bizarre affair to the police and we understand that an armed guard was placed there.”

Already we see a lot of discrepancies from the story as it’s usually told these days, but it gets even more complicated and weird. Following that article in the CRIFO Orbit, Stringfield met with another UFO enthusiast who had some corrections to the story. The businessman, he said, was actually a young volunteer policeman. Stringfield went to the chief of police to find out more. He learned the witness’s name, although he only gives his initials, C.F., and that he was 19 years old in either late June or early July 1955 when his sighting took place.

“The witness, C.F., was driving a Civil Defense truck at the time and as he was crossing a bridge in the Loveland area (there is one vehicular bridge into Loveland over the Little Miami River from Clermont County), he noticed four small figures on the river bank beneath the bridge. A terrible smell hung over the area. C.F. immediately drove to police headquarters in Loveland and reported the incident.”

Stringfield next went to talk to C.F., who didn’t really want to discuss his sighting since he’d been laughed at by too many people about it, but he did say that he’d seen “four more-or-less human-looking little men about three feet high,” and that he’d only seen them for about ten seconds. Since this interview took place within a year of the sighting, it’s probably as good as we can get now.

But things get even more complicated, because the very next chapter in the Close Encounter at Kelly publication is titled “The Hunnicutt Encounter at Branch Hill.” Now we have the name seen online attached to the businessman, Robert Hunnicutt, and the date May 25, 1955. Stringfield learned about this sighting from the police chief when they were discussing the other sighting.

The police chief was woken at about four in the morning by someone pounding on his front door. It was Robert Hunnicutt, a short-order cook in a Loveland restaurant, and he looked like he’d seen a ghost. He “told the police chief that while he was driving northeast through Branch Hill (in Symmes Township) on the Madeira-Loveland Pike, he had seen a group of ‘strange little men’ along the side of the road with ‘their backs to the bushes.’ Curious, he had stopped the car and gotten out. …[T]he witness claimed he had seen ‘fire coming out of their hands,’ and that a ‘terrible odor’ permeated the place. When Hunnicutt realized he was looking at something quite out of the ordinary he became frightened; jumping back into his car, he had driven directly to the police chief’s home.”

The chief of police knew Hunnicutt and while he believed the man had had a real fright, he didn’t believe the story as Hunnicutt told it. He also mentioned that Hunnicutt didn’t smell as though he’d been drinking alcohol. The police chief drove out to the spot Hunnicutt described and drove around looking for the creatures, without luck.

You better believe that Stringfield didn’t let this opportunity pass him by. He interviewed Robert Hunnicutt on September 1, 1956.

Hunnicutt said he was out at 3:30am on the night of the sighting because he was driving home from work, and he was driving down a slight hill when his headlights lit up three figures in the grass on the right-hand side of the road. He thought they were people kneeling in the grass for some reason, which is why he stopped his car.

“The figures were short, about three and a half feet in height, and they stood in a roughly triangular position facing the opposite side of the road. […] The forward figure held his arms a foot or so above his head and it appeared to Hunnicutt as though he were holding a rod, or a chain, in this upraised position. […] Sparks, blue-white in color and two or three at a time, were seen jumping back and forth from one hand to the other, just above or below the ‘rod.’ It was Hunnicutt’s impression that the beings were concentrating on some spot directly across the road, although he could see nothing unusual in the woods to the west of the Pike.

“As Hunnicutt got out of the left side of his car, the forward figure lowered his arms and near his feet appeared to release whatever he had been holding. To the witness, ‘it looked as if he tied it around his ankles.’ Then, as Hunnicutt stood by the left side of the car, all three figures simultaneously turned slightly toward their left so that they now faced the witness. Motionless, and without sound or change of expression, they stared directly at him. In the car lights Hunnicutt was able to observe a number of details.

“This most extraordinary trio was made up of three humanoid figures of a greyish color—approximately the same shade of grey for their heads as for their ‘garments.’ ‘Fairly ugly’ were the words Hunnicutt used to describe them. A large, straight mouth, without any apparent lip muscles, crossed nearly the entire lower portion of their faces—an effect which reminded the witness of a frog. The nose was indistinct, with no unusual feature that the witness could discern. The eyes seemed to be more or less normal, except that no eyebrows could be seen. The pate was bald and appeared to have rolls of fat running horizontally across the top, rather like the corregated [sic] effect of a doll’s painted-on hair—except that there was no difference in color.

“The most remarkable feature was the upper torso: the chest was decidedly lopsided. On the right side it swelled out in an unusually large bulge that began under the armpit and extended down to the waist, giving the figures a markedly asymmetrical appearance. The arms seemed to be of uneven length, the right being longer than the left, as though to accommodate this unusual feature. […] Hunnicutt saw nothing unusual about the hands, although he could not say how many fingers they had. […] He could see no feet, but the figures stood in six-inch high grass.”

Hunnicutt described the creatures’ movements as graceful, and he only noticed the smell when he got back into his car and drove off. He described it as “a combination of ‘fresh-cut alfalfa, with a slight trace of almonds,’” which sounds wonderful to me. He also said that a few months later, possibly July or August, he was driving the same stretch of road with his girlfriend and they both noticed the same smell. He stopped, but they didn’t see anything unusual.

After that, the publication goes on to talk about various UFO sightings in the area, so that’s all we have of first-hand accounts of the Loveland frogman.

It’s obvious that people have conflated the two different 1955 sightings, mixing them up so that some retellings repeat information from the original CRIFO Orbit report and others include more information from the Close Encounter at Kelly publication.

Were the creatures aliens, as Stringfield thought? Talking about potential aliens is beyond the scope of this podcast, but I will point out that organisms that evolved on a different planet are unlikely to look anything like humans or other tetrapods. Tetrapods are animals with four limbs of one kind or another, which includes mammals, reptiles, birds, and amphibians on Earth, and apparently also includes most aliens as seen in popular culture. But even on Earth, not every living thing has four limbs—in fact, most things don’t. Just think about jellyfish, octopuses, starfish, spiders, flies, centipedes, slugs, and trees.

But don’t forget about C.F.’s short report about what he saw. We don’t know when his sighting took place but it was probably during the day. All he saw was “four small figures on the river bank beneath the bridge” as he drove over the bridge, along with a terrible smell. He didn’t describe the smell, but most terrible smells near a road are rotting roadkill…and roadkilled animals attract a specific type of bird: vultures. Both turkey vultures and black vultures are common throughout Ohio and surrounding areas, and both are extremely large birds. C.F. didn’t get a good look and was also looking down at them from the bridge as he drove over. Four vultures sitting around a dead animal might easily look like four small human-like figures from a distance, especially when seen at such a strange angle.

As for Hunnicutt’s sighting, remember that it came only a few months after C.F.’s. Both C.F. and Hunnicutt knew the chief of police, so it’s also possible they had other acquaintances in common. C.F. had stopped talking about his sighting after he’d been laughed at by others who didn’t believe him, but it’s possible that Hunnicutt had heard the story. And remember, people see what they expect to see. If Hunnicutt was driving home after a tiring day at work, he might even have fallen asleep, his car drifted to a stop, and he dreamed he met the same weird creatures that C.F. saw.

Then again, I wasn’t there and it’s not fair for me to look back on a secondhand account from 67 years ago and decide that the witness dreamed it all. So we’ll just have to admit that the Loveland frog-man as seen in 1955, 1972, and 2016…might have been something truly strange after all.

Happy Halloween!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!