Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:57 — 21.1MB)

Subscribe: | More

To celebrate my new book, Skyway, this week let’s learn about sky animals! They’re fictitious, but could they really exist? And what animals are really found in the high atmosphere?

You can order a copy of Skyway today on Kindle or other ebook formats! It’s a collection of short stories published by Mannison Press, with the same characters and setting from my novel Skytown (also available)!

Further reading:

“The Horror of the Heights” by Arthur Conan Doyle (and you can even listen to a nice audio version at this link too!)

Charles Fort’s books are online (and in the public domain) if not in an especially readable format

Further Listening:

unlocked Patreon episode The Birds That Never Land

Rüppell’s vulture:

The bar-headed goose:

The common crane:

Bombus impetuosus, an Alpine bumblebee that lives on Mount Everest:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’ve got something a little different. Usually I save the weirder topics for Patreon bonus episodes, and in fact I had originally planned this as a Patreon episode. But I have a new book coming out called Skyway, so in honor of my new book, let’s learn about some sky animals!

Skyway is a collection of short stories about the same characters in my other book Skytown, so if you’ve read Skytown and liked it, you can buy Skyway as of tomorrow, if you’re listening on the day this episode goes live. I’ll put links to both books in the show notes so you can buy a copy if you like. The books have some adult language but are appropriate for teens although they’re not actually young adult books.

Anyway, the reason I say this episode is a little different is because first we’re going to learn about some interesting sky animals that are literary rather than real. Then we’ll learn about some animals that are real, but also interesting—specifically, animals that fly the highest.

Back before airplanes and other flying machines were invented, people literally weren’t sure what was up high in the sky. They thought the sky continued at least to the moon and maybe beyond, with perfectly breathable air and possibly with strange unknown animals floating around up there, too far away to see from the ground.

People weren’t even sure if the sky was safe for land animals. When hot-air balloons big enough to carry weight were invented in the late 18th century, inventors tried an important experiment before letting anyone get in one. In 1783 in France, a sheep, a duck, and a rooster were sent aloft in a balloon to see what effects the trip would have on them. The team behind the flight assumed that the duck would be fine, since ducks can fly quite high, so it was included as a sort of control. They weren’t sure about the rooster, since chickens aren’t very good flyers and never fly very high, and they were most nervous about the sheep, since it was most like a person. The balloon traveled about two miles in ten minutes, or 3 km, and landed safely. All three animals were fine.

After that, people started riding in balloons and it became a huge fad, especially in France. By 1852 balloons were better designed to hold more weight and be easier to control, and that year a woman dressed as the goddess Europa and a bull dressed as Zeus ascended in a balloon over London. But the bull was obviously so frightened by the balloon ride that the people watching the spectacle complained to the police, who charged the man who arranged the balloon ride with animal cruelty. The bull was okay, though, and no one made him get in a balloon again.

After airplanes were invented and became reliable, if not especially safe, the world went nuts about flying all over again. In 1922 Arthur Conan Doyle published a story called “The Horror of the Heights,” about a pilot who flew high into the sky and came across sky animals. You can tell from the story’s title that things did not go well for the main character.

The story is written as though it’s an excerpt from a journal kept by the main character, named Joyce-Armstrong. Early on, Joyce-Armstrong is talking about height records achieved by pilots and that no one has had any trouble that high in the sky. He says,

“The thirty-thousand-foot level has been reached time after time with no discomfort beyond cold and asthma. What does this prove? A visitor might descend upon this planet a thousand times and never see a tiger. Yet tigers exist, and if he chanced to come down into a jungle he might be devoured. There are jungles of the upper air, and there are worse things than tigers which inhabit them.”

After that are some really lovely descriptions of the pilot’s ascent into the sky, trying for both a height record and to see the so-called jungle of the upper air. In the story, he climbs to over 41,000 feet in an open cockpit monoplane without any special equipment. He’s wearing, like, a nice warm hat and wool socks. In actuality, at 40,000 feet, or 12,000 meters, the temperature can be as low as -70 degrees F, or -57 Celsius.

Anyway, Joyce-Armstrong writes in his journal, “Suddenly I was aware of something new. The air in front of me had lost its crystal clearness. It was full of long, ragged wisps of something which I can only compare to very fine cigarette smoke. It hung about in wreaths and coils, turning and twisting slowly in the sunlight. As the monoplane shot through it, I was aware of a faint taste of oil upon my lips, and there was a greasy scum upon the woodwork of the machine. Some infinitely fine organic matter appeared to be suspended in the atmosphere. There was no life there. It was inchoate and diffuse, extending for many square acres and then fringing off into the void. No, it was not life. But might it not be the remains of life? …The thought was in my mind when my eyes looked upwards and I saw the most wonderful vision that ever man has seen. …Conceive a jelly-fish such as sails in our summer seas, bell-shaped and of enormous size—far larger, I should judge, than the dome of St. Paul’s. It was of a light pink colour veined with a delicate green, but the whole huge fabric so tenuous that it was but a fairy outline against the dark blue sky. It pulsated with a delicate and regular rhythm. From it there depended two long, drooping, green tentacles, which swayed slowly backwards and forwards. This gorgeous vision passed gently with noiseless dignity over my head, as light and fragile as a soap-bubble…”

After that, Joyce-Armstrong sees more of the sky jellyfish and some long smoke-like creatures that he calls the serpents of the outer air. And then he’s attacked by a huge purplish creature sort of like a sky octopus with sticky tentacles. He escapes and flies home, writes his journal entry, and says he’s going back to capture one of the smaller sky jellyfish and bring it back to show everyone. And after that, the journal ends except for a terrible addendum scrawled in pencil on the last page. It’s a fun story that you can read for free online, since it’s in the public domain. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

Arthur Conan Doyle is the same author who invented Sherlock Holmes, if the name sounds familiar. But he wasn’t the first one to imagine strange high-altitude sky animals. He was influenced by the writings of a man named Charles Fort. Fort liked to collect the accounts of weird happenings reported in newspaper articles and magazines, and he published his first book in 1919. If you’re a Patreon subscriber you may remember Fort from a bonus episode last October where I talked about a few of his animal-related cases. I’d unlock the episode for anyone to listen to except that I just re-listened to it myself, and at the end I talk about my recent eye surgery in really way too much detail. So I won’t unlock it, but I will say that Fort had a weird writing style that can be hard to follow. He likes to present outlandish theories as though he’s deadly serious, then claim that he’s only joking, then say, “Well, maybe I’m not joking.” His main goal is to make readers think about things that would never have occurred to them.

Fort was especially interested in falls of fish and frogs and other things, which we talked about in episode 140 last October. In his first book he suggested there are places in the sky where items collect, and that occasionally things fall out of those places. He called this the Super-Sargasso Sea, after the Sargasso Sea that’s supposed to be a becalmed area of the ocean where sailing ships get caught because there’s no wind or currents. The Sargasso Sea is a real place in the North Atlantic Ocean that has clear blue water and which is full of a type of seaweed called Sargassum. It’s also full of plastic, unfortunately, since that’s where the North Atlantic garbage patch is.

But Fort described his Super-Sargasso Sea as something between another dimension and an alien world that just brushes up against the earth’s atmosphere. He pointed out that this theory made as much sense as any other explanation for falling frogs and other things, which of course is why he suggested it. He didn’t actually believe it.

This is how Fort describes the super-Sargasso Sea: “I think of a region somewhere above this earth’s surface in which gravitation is inoperative…. I think that things raised from this earth’s surface to that region have been held there until shaken down by storms…. [T]hings raised by this earth’s cyclones: horses and barns and elephants and flies and dodoes, moas, and pterodactyls; leaves from modern trees and leaves of the Carboniferous era…. [F]ishes dried and hard, there a short time; others there long enough to putrefy…. [O]r living fishes, also—ponds of fresh water: oceans of salt water.

“But is it a part of this earth, and does it revolve with and over this earth—

“Or does it flatly overlie this earth…?

“I shall have to accept that, floating in the sky of this earth, there often are fields of ice as extensive as those on the Arctic Ocean—volumes of water in which are many fishes and frogs—tracts of lands covered with caterpillars—

“Aviators of the future. They fly up and up. Then they get out and walk. The fishing’s good: the bait’s right there. … Sometime I shall write a guide book to the Super-Sargasso Sea, for aviators, but just at present there wouldn’t be much call for it.”

That quote is actually cobbled together from pages 90-91, 179, and 182 of my copy of The Complete Books of Charles Fort, because one thing Fort is not good at is a straightforward, clear narrative. Reading his books is like experiencing someone else’s fever dream. But you can definitely see where Conan Doyle got his inspiration for “The Horror of the Heights.”

These days we know a lot more about the sky—or, more technically, about the atmosphere that surrounds the Earth. Researchers have labeled different parts of the atmosphere since the different layers have different properties. The layer closest to the earth, the one that we breathe and live in, is the troposphere. That’s where weather happens, that’s where most clouds are, and that’s where 99% of the water vapor in the entire atmosphere is located. The troposphere extends about 6 miles above the earth, or 10 km, or 33,000 feet. Mount Everest is 29,000 feet high, by the way, or 8,850 meters. Above the troposphere is the stratosphere, which extends to about 31 miles above the earth, or 50 km.

The jet stream, a steady wind that commercial jet planes use to help them cross oceans and continents faster, occurs roughly where the troposphere becomes the stratosphere. Above the jet stream, there’s hardly any turbulence. There are no updrafts, basically no weather, just increasingly thin air. Weather balloons and spy planes ascend into the stratosphere and that’s also where the ozone layer is, but there’s basically not much up that high.

Above the stratosphere is the mesosphere, where the air is too thin for any animal known to breathe, plus the air pressure is only about 1% of the pressure found at sea level. There just aren’t very many air molecules in the mesosphere. This is where meteors typically burn up, and the only vehicles that fly there are rockets. It extends to about 53 miles above the earth, or 85 km, and above that is the thermosphere, the exosphere, and then empty space, although it’s hard to know exactly where the thermosphere and exosphere end and space begins. It’s so far away from the earth’s surface that some satellites orbit within the thermosphere, and that’s where the northern and southern lights are generated as charged particles from the sun bounce against molecules.

But let’s return to the troposphere, our comfortable air-filled home. As far as we know, there aren’t any animals that live exclusively in the air and never land. Even the common swift, which lives almost its entire life in the air, catching insects and sleeping on the wing, has to land to lay eggs and take care of its babies. But what animals fly the highest?

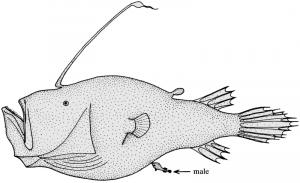

As far as we know, the highest-flying bird is Rüppell’s vulture, an endangered bird that lives in central Africa. It’s been recorded flying as high as 37,000 feet, or 11,300 meters, and we know it was flying at 37,000 feet because, unfortunately, it was sucked into a jet engine and killed. There’s so little oxygen at that height that a human would pass out pretty much instantly, but the vulture’s blood contains a variant type of hemoglobin that is more efficient at carrying oxygen so that it gets more oxygen with every breath. It has a wingspan of 8 ½ feet, or 2.6 meters, and is brown or black with a lighter belly and a white ruff around the neck. Its tongue is spiky to help it pull meat off the bones of the dead animals it eats, but if there’s no meat left on a carcass, it will eat the hide and even bones. The more I learn about vultures, the more I like them.

Any bird that migrates above the Himalayas has to be able to fly incredibly high, since that’s where Mount Everest is and many other mountains that reach nearly into the stratosphere. The bar-headed goose has been recorded flying at 29,000 feet, or 8,800 meters, and in fact, mountaineers climbing Mount Everest have claimed to see and hear the geese flying overhead. The bar-headed goose has the same variant hemoglobin that Rüppell’s vulture has so it absorbs more oxygen with every breath.

The bar-headed goose is pale gray with black and white markings, especially black stripes on its head. It’s not an especially big goose, with a wingspan of about five feet, or 160 cm. It nests in China and Mongolia during the summer, then migrates to India and surrounding areas for the winter, and it generally crosses the Himalayas at night when winds aren’t as high.

The common crane is another high-flying bird, which has been recorded flying at 33,000 feet, or 10,000 meters, above the Himalayas. It’s a large bird with long legs and a wingspan of nearly 8 feet, or 2.4 meters. It’s gray with a red crown on its head and a white streak down its neck, and a tail that’s not so much a tail as just a bunch of floofy feathers stuck to its butt. Supposedly it flies so high to avoid eagles, but it’s a strong bird with a stabby beak that has been observed fighting eagles that attack it. It nests in Russia and Scandinavia but flies to many different wintering sites across Europe, Africa, and Asia.

So those are the three highest-flying birds known, but what about insects? How high can an insect fly?

Most insects can’t fly if the air is too cold, typically if it’s below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, or 10 degrees Celsius. Since the air is that cold just a few thousand feet above ground, that means most insects don’t fly very high, especially small ones. But not all of them.

Because insects are so small and lightweight, they’re often carried by the wind even if they aren’t technically flying, an activity called kiting. In 1961 during a study of insect migrations, an insect trap installed on an airplane caught a single winged termite at 19,000 feet, or 5.8 kilometers above sea level. An insect trap on a weather balloon collected a small spider at 16,000 feet, or 5 km. If you’re wondering how the spider got in the air in the first place, many small spider species travel to new habitats by ballooning, which in this case has nothing to do with a balloon. The spider lifts its abdomen until it feels a breeze, and then it spins a short piece of silk. The breeze lifts the silk and therefore the spider and carries it sometimes long distances.

Some bumblebee species live and fly just fine at high altitudes. The bumblebee Bombus impetuosus lives on Mount Everest, although not at its very top because nothing grows that high. It lives at around 10,600 feet, or 3,250 meters, and studies of how it flies show that it actually beats its wings in a different way from other bumblebees in order to fly at high altitudes where the air is thin.

So maybe there aren’t weird jellyfish-like creatures floating around in the stratosphere, but there are certainly other animals that occasionally reach incredible heights. So I guess the only thing the fictional pilot Joyce-Armstrong really had to worry about was freezing to death.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes for as little as one dollar a month.

Thanks for listening!