Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:33 — 11.8MB)

Thanks to Mia for suggesting the black rhino this week! We’ll also learn about other rhinos and their relations, including a mystery rhino.

Further reading:

Photos suggest rhino horns have shrunk over past century

The Blue Rhinoceros – In Quest of the Keitloa

A rhino with a very small third horn:

Some rhinos have really big second horns [photo by David Clode and taken from this site]:

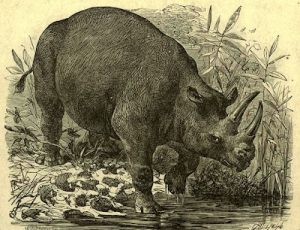

The “blue rhinoceros,” or keitloa, as illustrated in the mid-19th century:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to talk about an animal I can’t believe we haven’t covered before. Thanks to Mia for suggesting the rhinoceros, specifically the black rhino! We’ll also learn about a mystery rhino.

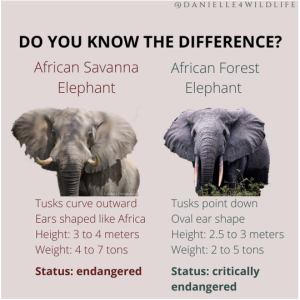

We’ve talked about elephants lots of times, hippos quite a few times, and giraffes a couple of times, but pretty much the only episodes where we discussed a rhinoceros were 5 and 256. Episode 256 was mostly about mammoths, although we talked very briefly about the woolly rhinoceros, while episode 5 was about the unicorn and didn’t actually specifically talk about the rhino. So after almost 350 episodes of this podcast, one of the most amazing animals alive is one we literally haven’t learned about! Let’s fix that now.

Most people are pretty familiar with what a rhinoceros looks like. Basically, it’s a big, heavy animal with relatively short legs, a big head that it carries low to the ground like a bison, and at least one horn that grows on its nose. It’s usually gray or gray-brown in color with very little hair, and its skin is tough. It eats plants.

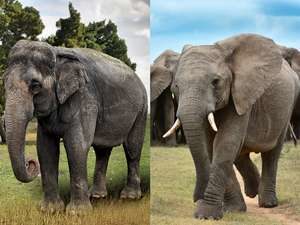

The rhinoceros isn’t related to the elephant or the hippopotamus. It’s actually most closely related to the horse and the tapir, which are odd-toed ungulates. The rhino has three toes on each foot, with a little hoof-like nail covering the front of each toe, but the bottom of the rhino’s foot is a big pad similar to the bottom of an elephant’s foot.

The rhino’s nose horn isn’t technically a horn because it doesn’t have a bony core. It’s made of long fibers of keratin all stuck together, and keratin is the same protein that forms fingernails and hair. That makes it even weirder that some people think a rhinoceros horn is medicine. It’s literally the same protein as fingernails, and no one thinks of fingernails are medicine. The use of rhinoceros horn as medicine isn’t even all that old. Ancient people didn’t think it was medicine, but some modern people do, and they’ll pay a whole lot of money for part of a rhino horn to grind up and eat. Seriously, they might as well be eating ground-up fingernails. (That’s gross.)

Because rhino horns are so valuable, people will kill rhinos just to saw their horns off to sell. That’s the main reason why most species of rhino are so critically endangered, even though they’re protected animals. Sometimes conservationists will sedate a wild rhino and saw its horn off, so that poachers won’t bother to kill it. A 2022 study determined that the overall size of rhino horns has shrunk over the last century, probably for the same reason that many elephants now have overall smaller tusks. Poachers are more likely to kill animals with big horns, which means animals with smaller horns are more likely to survive long enough to breed.

The species of rhinoceros alive today are native to Africa and Asia, but it used to be an animal found throughout Eurasia and North America. It’s one of the biggest animals alive today, but in the past, some rhinos were even bigger. We’ve talked about Elasmotherium before, which lived in parts of Eurasia as recently as 39,000 years ago. It had long legs and could probably gallop like a horse, but it was the size of a mammoth. It also probably had a single horn that grew in the middle of its forehead, which is why it’s sometimes called the Siberian unicorn.

We’ve also talked about Paraceratherium before. It was one of the biggest land mammals that ever lived, and while it didn’t have a horn, it was a type of rhinoceros. It lived in Eurasia between about 34 and 23 million years ago, and it probably stood about 16 feet tall at the shoulder, or 5 meters. The tallest giraffe ever measured was 19 feet tall, or 5.88 meters, at the top of its head. Paraceratherium had a long neck, possibly as much as eight feet long, or 2.5 meters, but it would have held its neck more or less horizontal most of the time. It spent its time eating leaves off of trees that most animals couldn’t reach, and when it raised its head to grab a particularly tasty leaf, it was definitely taller than the tallest giraffe, and taller than any other mammal known.

While rhinos are famous for their horns, not every rhinoceros ancestor had a horn. But because rhino horns are made of keratin and not bone, we don’t always know if an extinct species had a horn. Most of the time the horns rotted away without being preserved. We do know that some ancient rhinos had a pair of nose horns that grew side by side, that some had a single nose horn or forehead horn, that some had both a nose horn and a forehead horn, and that some definitely had no horns at all.

The rhinos alive today have either one or two horns. The Indian rhinoceros has one horn on its nose, and the closely related Javan rhino also only has one horn. The Sumatran rhino has two horns, as do the white rhino and the black rhino. Sometimes an individual rhino will develop an extra horn that grows behind the other horn or horns and is usually very small. This is extremely rare and seems to be due to a genetic anomaly. There are even reports of rhinos that have four horns, all in a row, but the extra ones, again, are very small.

Mia specifically wanted to learn about the black rhino. It and the white rhino are native to Africa. You might think that the white rhino is pale gray and the black rhino is dark gray, but that’s actually not the case. They’re both sort of a medium gray in color and they’re very closely related. It’s possible that the word “white” actually comes from the Dutch word for “wide,” referring to the animal’s wide mouth. The black rhino has a more pointed lip that looks a little bit like a beak.

One interesting thing about the black and white rhinos is that neither species has teeth in the front of its mouth. It uses its lips to grab plants instead of its front teeth, and then it uses its big molars to chew the plants. The white rhino mostly eats grass while the black rhino eats leaves and other plant material.

A big male black rhino can stand over 5 1/2 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.75 meters, and is up to 13 feet long, or 4 meters. It can weigh as much as 4,000 lbs, or 1,800 kg. This sounds huge and it is, but it’s actually smaller than the white rhino, which is the biggest rhino alive today. A big male white rhino can stand over 6 1/2 feet tall at the shoulder, or 2 meters, can be 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters, and can weigh up to 5,300 lbs, or 2,400 kg. These are really really big animals. Nothing much messes with the rhino because it’s so big and heavy, its skin is so tough, and it can do a lot of damage with its horn if it wants to. The rhino doesn’t see very well, but it has good hearing and a good sense of smell.

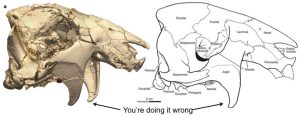

The nose horn is always the bigger one in species that have two horns, and in the black rhino it can grow quite long. One nose horn was measured as being over 4 1/2 feet long, or 1.4 meters, although most are only about 20 inches long, or 50 cm. The rear horn, which grows roughly over the eyes, is about half the length of the front horn, and is sometimes no more than a little bump. But some black rhinos found in South Africa have a rear horn that’s at least as long as the front horn, and sometimes longer, and that brings us to our mystery rhino.

A rhino with this trait is referred to as a keitloa, a word taken from the Tswana language spoken in the area. In the 19th century, the keitloa was referred to by European colonizers as the blue rhinoceros. The blue rhino wasn’t blue, but it was considered quite rare and different from the ordinary black rhino. It was supposed to be bigger and and even more solitary than the black rhino.

Until 1881, many scientists thought the keitloa was a separate species of rhino from the black rhino, which it otherwise resembled. In 1881, though, a study of black rhinos and blue rhinos determined that they were the same species. A century later, in 1987, scientists found that black rhinos with better access to water grew larger horns than black rhinos living in dryer areas.

There are a number of subspecies of black rhino recognized by scientists, some of them still alive today and some driven recently to extinction. Some people still think that the keitloa may be a separate subspecies of black rhino. That’s one of many reasons why it’s so important to protect all rhinoceroses and their habitats, so we can learn more about these amazing animals.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!