Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:47 — 13.0MB)

This week thanks to Romy, who suggested the topic of hedgehogs! And researching hedgehogs led me to their only close relation, the moonrat.

Hedgehogs are adorable:

Pictures of listener QuillviaPlath’s adorable friend Delilah, an African pygmy hedgehog. Delilah has crossed the Rainbow Bridge since these pictures were taken, but QuillviaPlath has a rescue hedgehog named Lily now and will soon be adopting another rescue named Toodles too!

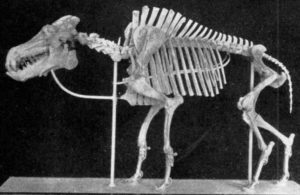

Moonrats are a little less adorable but still cute:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about a humble little animal that’s well-known in much of Europe, Asia, and Africa, but totally unknown in the Americas except as a pet. It’s the hedgehog, a suggestion from Romy. Thank you, Romy! We’ll also learn about the hedgehog’s closest relation, the moonrat.

There did actually used to be a hedgehog native to North America, but it went extinct some 50 million years ago. The hedgehogs alive today pretty much haven’t changed in about 15 million years. The North American hedgehog is called Silvacola and only grew a few inches long, or maybe 7 cm. It lived in what is now British Columbia, Canada. We don’t know if it had quills, but the hedgehogs living in Europe at the same time as Silvacola lived had already evolved quills, so maybe it did.

I have seen exactly one hedgehog in my life, a pet named Button. I got to pet her and everything. She was very sleepy, though, because it was daytime and hedgehogs are nocturnal. But I can verify that hedgehogs do have spines on the back and sides, although if you pet the hedgehog properly you won’t get your fingers poked by the spines. I can also verify that hedgehogs are adorable.

But other than adorable and prickly, what are hedgehogs? Are they related to porcupines? Are they related to hogs? Do they really live in hedges?

The answers are no, no, and yes. Thanks for listening. You can find Strange Animals—ha ha, just kidding!

There are a number of hedgehog species in five separate genera. A few species have been domesticated, although it’s illegal in many places to keep a wild hedgehog as a pet. In some places it’s illegal to keep a hedgehog as a pet at all, since hedgehogs can become invasive pests if released into the wild in areas where they shouldn’t be. This has happened in New Zealand and a few other places, where introduced hedgehogs have no natural predators and have become so numerous they’ve caused damage to the local ecosystems. The hedgehog is an omnivore, and will eat bird eggs, insects, frogs and toads, snails, plants, and pretty much anything else. It’s especially damaging to shore birds that nest on the ground. But in its natural habitat, the hedgehog plays an important role as both a predator of small animals, including garden pests, and as prey to larger animals like foxes, badgers, and owls.

The hedgehog will also eat small snakes, and actually has some natural immunity to certain snake venoms. Of course, if a snake injects enough venom it will overwhelm the hedgehog’s protections and make it sick or kill it anyway. It also has resistance to toxins and will eat toxic toads that would kill other animals. But the hedgehog’s best protection is its spines, more properly called quills. If a hedgehog feels threatened, it will roll itself into a tight ball with its quills sticking out.

The quills are hairs that are hollow and stiffened with keratin. Good old keratin. You know, keratin is the same tough material that fur and fingernails and rhinoceros horns and hooves and baleen are made of. European hedgehogs are famous for the number of fleas they carry, a specific species of flea called the hedgehog flea. Who named that? They were a genius. Hedgehog fleas won’t infest dogs or cats. They only like hedgehogs.

The hedgehog is a good digger and sometimes digs burrows to sleep in during the day. It’s adaptable to many habitats but likes woodlands, meadows, and, yes, hedgerows where it can find lots of food. It has a pig-like snout, short legs, a little stub of a tail, and small ears. Baby hedgehogs are born with a protective membrane over their quills. It grows to around a foot long, or 30 cm, although many of the species are typically smaller than that. Most hedgehogs are brown but some are naturally cream-colored, a rare variety called blonde. This color is bred for in domesticated hedgehogs. Button the hedgehog is blonde with a dark spot on her back, which is why she’s named Button.

The population of West European hedgehogs has decreased substantially in the last few decades, which has conservationists worried. A 2016 study reported that the population has declined over 7% in the UK over the last 50 years, with similar declines in parts of Europe like Sweden and Belgium. Researchers speculate this may be due to habitat loss.

The hedgehog can hibernate although it doesn’t always. It may hibernate in piles of leaves or sticks, or in a burrow it digs underground, or somewhere else that’s protected from predators and cold. If you’ve gathered wood for a bonfire, make sure to check the pile for sleeping hedgehogs before you get the matches out.

One of the most persistent legends about the hedgehog is that it rolls on fruit, especially apples, in order to stick its quills into the fruit. Then it goes home to its burrow, carrying the fruit on its quills to eat later.

So, do hedgehogs actually do this? Probably not. Some observers say hedgehogs will roll in leaves and allow the leaves to stick to its quills, possibly as a form of camouflage. It would be easy for one to accidentally pick up a small rotten apple this way, giving rise to the legend, although the quills aren’t strong enough to hold a large apple without breaking. The sites I read online all say that hedgehogs don’t bring food back to the burrow to eat later, but T.H. White shares an anecdote to the contrary in his Book of Beasts. This is a translation of a 12th century bestiary, and his anecdote appears in a note on page 95. The text repeats the story of hedgehogs carrying apples home, and White adds:

“The Hedgehog constructs a humble nest in ditches, and there it hibernates. In 1939, the present translator dug out such a nest, near an orchard, with an Irish laboring companion who proceeded to tell him that hedgehogs carried apples to their nests on their spines—an anecdote which the translator had just been reading in this manuscript, eight hundred years older than the Irishman. The latter asserted the truth of his statement with passion, pointing to the apples, which were indeed there, and had punctured bruises on them. But the creature had probably trundled them there with its nose, subsequently making the punctures when it curled up to sleep on top of them.”

I haven’t found anyone else who reports seeing a hedgehog push an apple home with its nose, or anything else for that matter. But the apples were in the hedgehog’s nest. T.H. White saw them. It could be the apples had fallen from a nearby tree and rolled into the ditch on their own, and the hedgehog just happened to nest on them. Then again, one source I found mentions that hedgehogs may anoint themselves with apple juice to help repel fleas and other parasites. This seems a little on the farfetched side, but the hedgehog does do a weird thing called anointing that might have something to do with controlling parasites. No one’s sure what it’s for.

Anointing seems to be triggered when a hedgehog encounters a new or unusual odor. The hedgehog starts foaming at the mouth, often contorting its body oddly, and then it licks the foam onto its quills. This happens with domesticated hedgehogs as well as wild ones, and one site I read mentions that it may happen if you handle a pet hedgehog after putting hand lotion on.

So what is the hedgehog related to? It’s not a rodent, so it’s not related to porcupines. It’s a placental mammal so it’s not related to echidnas, which are monotremes. Both porcupines and echidnas evolved quills for protection independently. The hedgehog is probably most closely related to the shrew, but the other member of its family is an animal called the moonrat.

The moonrat lives in Southeast Asia, specifically Thailand, Borneo, and Myanmar, and shares a lot of characteristics with the hedgehog, like being omnivorous and digging burrows, but it doesn’t have quills. It looks a lot like the Virginia opossum, or as it’s properly called around where I live, the possum. But the possum is a marsupial, and again, the moonrat, like the hedgehog, is a placental mammal. It also looks a little like a rat, but the rat is a rodent and the moonrat isn’t a rodent.

The moonrat has a relatively long, skinny tail that’s mostly bare of fur and is actually scaly, which makes its tail look kind of like a snake. It also hisses like a snake (it’s not a snake). (Also going to point out that the possum hisses too.) The moonrat also has a long, thin muzzle, small rounded ears, and short legs. It grows to about a foot and a half long, not counting the tail, which can be nearly as long as the body. A foot and a half is about 40 cm. One subspecies of moonrat has light gray or white fur on its head and forequarters except for a black mask, while the rest of its body is black. Another subspecies is mostly white.

The moonrat prefers jungles and forests and is mostly nocturnal. It eats pretty much anything, but it especially likes insects, crabs, worms, and frogs, and will even eat fish when it can catch one.

One interesting thing about the moonrat is its smell. The moonrat marks its territory with a scent that smells like ammonia. You know what else smells like ammonia? Cat pee. That is not a good smell, if you’ve ever had to clean out a cat’s litter box that should have been cleaned out a lot earlier. It also smells kind of like rotten onions. As a result of its scent glands for marking territory, the moonrat smells pretty bad to human noses. But people do occasionally eat it, just as they sometimes eat hedgehogs.

People are omnivores too, after all. But, you know, maybe don’t eat animals that smell like ammonia.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at a new URL! I finally had to move to a real podcast hosting platform since I had topped out the memory and usage available without one. Our website is now at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. I will keep the old website up but it won’t be updated. The podcast feed shouldn’t change unless I’ve really messed something up, in which case you probably aren’t hearing this.

If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, or just want a sticker, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast where you can get bonus episodes for as little as one dollar a month donation.

Thanks for listening!