Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:49 — 28.3MB)

Subscribe: | More

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Don’t forget our Kickstarter! I can’t believe it reached its funding goal THE FIRST DAY!

We’re getting so close to Halloween! This week we’ll learn about Mothman! Is it a moth? Is it a ghostly entity from another world? Is it a bird? (hint: it’s probably a bird)

Sandhill cranes (not mothmen):

A Canada goose (not mothman):

A great bustard (not mothman):

A green heron (definitely not mothman but look at those big cute feets and that telescoping neck):

A barn owl’s eyes reflecting red (photo taken from Frank’s Barn Owls and Mourning Doves, which has lots of lovely pictures):

Barn owls look like strange little people while standing up straight:

Barn owls got legs:

All owls got legs:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week for monster month, let’s cover a spooky monster with a silly name, mothman! We’ll go over the facts as clearly as possible and see if we can figure out what kind of creature mothman might be.

First, though, a quick reminder that our Kickstarter is still going on if you’re listening to this before Nov. 5, 2021! There’s a link in the show notes if you want to go look at it. We actually reached our funding goal on the very first day, so thank you all so much for backing the project, sharing the project on social media, or just putting up with me spamming you about it all month.

Now, on to mothman.

As far as anyone can tell, it all started in 1966, specifically November 12, outside of Clendenin, West Virginia, in the eastern United States. Five men were digging a grave in a cemetery outside of town when one of them saw something big fly low across the trees and right over their heads. The witness thought it looked like a man with wings, but with red eyes and an estimated wingspan of 10 feet, or 3 meters. This definitely happened, even though it sounds like the opening scene of a scary movie.

That story didn’t come to light until after the next sighting hit the newspapers and caused a lot of excitement. The second sighting took place only three days later near Point Pleasant, West Virginia, in the McClintic Wildlife Area. Locals call it the TNT area, since explosives were stored there during WWII. The TNT area is about 70 miles, or over 110 km, away from Clendenin, which has led to a lot of people discounting the gravedigger’s sighting. We’ll come back to that later, though.

On Nov. 15, 1966, two young couples decided to go out driving. They were bored and it was a cold, clear Tuesday night. Remember, this was the olden days when there weren’t as many things to do as there are today. You could watch TV, but only if there was something you wanted to watch on one of the three TV stations available in the United States. If you wanted to watch a movie, you had to go to a movie theater, and so on.

Anyway, Steve Mallette and his wife Mary and their friends Roger Scarberry and his wife Linda went out driving that Tuesday night. Toward midnight, as they drove through the TNT area, their car came over a hill and they saw a huge creature in front of them.

Some 35 years later, in July 2001, Linda gave an interview to the author of the book I used as my main reference for this episode, called Mothman: The Facts Behind the Legend. She mentioned details that aren’t in any of the newspaper articles from 1966, or that give a better explanation of what happened than the articles did. There’s always a possibility that after 35 years, her memory wasn’t accurate, so I’m mostly going by the newspaper articles for my information, but she does mention something interesting in that interview.

She says this about the very first sighting of the creature:

“We had just topped a hill in the TNT area, and when the headlights of our car hit it, it looked directly at us, as if it was scared. It had one of its wings caught in a guide wire near a section of road close to the power plant, and was pulling on its wings with its hands, trying to free itself. Its hands were really big. It was really scared. We stopped the car and sat still while it was trying to free itself from the wire. We didn’t sit there long, just long enough to scare it, I think. It seemed to think we were going to hurt it. We were all screaming, ‘Go! Go! Go!’ But, we couldn’t perform the actual action of leaving the scene. It was like we were hypnotized. It finally got its wing loose from the wire and ran into the power plant. I felt sorry for it.”

In the original reports from 1966, the couples said the creature was 6 or 7 feet tall, or 1.8 to 2.1 meters, with a wingspan of 10 feet, or 3 meters. Its eyes were big and glowed red in the car’s headlights and its wings were white and angel-like. Its body was gray. While it was a clumsy runner, it could fly at an estimated 100 mph, or 161 km/hour.

Let’s stop right here before we talk about what else happened that spooky night. A ten-foot wingspan is big for a bird but not unheard-of. The trumpeter swan, several species of vulture, Andean condor, Marabou stork, two species of pelican, and several species of albatross have wingspans of at least ten feet across. Some of those have wingspans of 12 feet, or 3.7 meters.

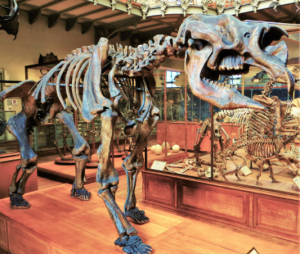

The heaviest bird that can still fly is probably the great bustard, which has a wingspan of up to 8 feet, or 2.5 meters. A big male can weigh up to 44 lbs, or 18 kg. Mothman is described as a man-sized creature with wings. Even if it was stick-thin, a person that tall would weigh far too much to get off the ground with a wingspan barely longer than its armspan.

So that’s one thing to keep in mind. Let’s find out what happened next on that cold November night.

After their initial fright, Roger Scarberry, who was driving, naturally decided to get out of the TNT area. He headed back to town. The newspaper articles report that the strange creature followed them for some distance, gliding above their car. All four of the people in the car were frightened, and after about half an hour they decided to go to the police. In her 2001 interview, Linda said,

“We wouldn’t have went to the police, but it kept following us. We saw it sitting in different places as we drove back down Route 62 toward Point Pleasant, and saw it sitting in various places once we got in town, too. It was as if it was letting us know that it could catch up to us, no matter where we went, or how fast we went there. When we first left the TNT area, it was sitting on the sign when we went around the bend and when the headlights hit it, it went straight up into the air, very fast. That’s when it followed us and hit the top of the car two or three times while we were going over one hundred miles per hour down Route 62, toward Point Pleasant. The last place we saw it was sitting on top of the flood wall. It was sitting crouched down, with its arms around its legs and its wings tucked against its back. It didn’t seem scared, then. I guess it figured out that we weren’t going to hurt it, so it followed us. We didn’t know what else to do but go to the police station.”

So, the people in the car initially saw the creature with its wing caught in a guide wire, and when it got its wing free, it ran clumsily into a nearby abandoned building. But Linda says they then saw it as they were driving away from the TNT area, presumably just a few minutes later, and that it was sitting on a sign and flew straight up in the air when the headlights lit it up.

Next, she said the car was going about 100 mph but the creature was flying above it, keeping pace, and even hit the top of the car a few times. No one said they had their head out the window to look up, so how did they know the creature was flying over their car? Presumably they assumed that’s what it was doing because it thumped the roof of their car a few times—but how do they actually know that’s what happened? They heard some thumps and made an assumption because they were scared, but at 100 mph on a back road a car is naturally going to be making a lot of noise and shaking a lot as it goes over uneven pavement. Not to mention that none of the newspaper reports mention that the creature hit the roof of their car.

I don’t think the creature was ever flying above their car. I also think the creature they saw initially was not the same creature they saw fly up from the sign. I especially don’t think the thing they saw repeatedly as they drove to town was the same one as the others. But we’ll come back to that again too in a few minutes.

The story appeared in the papers on Wednesday, November 16 and that evening, half the town went to the TNT area to look for the creature. They spotted it, too. Four people reported seeing a huge bird at 10pm on Wednesday night. The creature stared at them as they sat in their car, then flew away. Reporters also turned up another sighting of a creature with red-reflecting eyes a few hours’ drive away, also on Tuesday night, and the gravedigger’s story from several days before. By Thursday night an estimated 1,000 people arrived at the TNT area to look for the creature.

By the end of November 1966, though, things were quieting down. A November 22 article in the Huntington Herald-Dispatch is titled “Mason Bird-Monster Presumed Gone Now.” I’ll read part of the article.

“It was a week ago today that the first sighting was reported of a large red-eyed winged creature in the McClintic area. Since then there have been about 10 or more similar reports.

“The latest report was by four teenaged youths who said they saw a large bird with red eyes fly away from their car at a very high rate of speed. This was 3 a.m. Sunday.”

The article goes on to quote various authorities, including a wildlife biologist who suggested it might be a sandhill crane. It also ends with the suggestion that the sightings may lead to an eventual legend and tourism draw, which is exactly what happened, although it took almost 50 years for it to really gain traction.

The sandhill crane theory is repeated in a lot of newspapers and occasionally crops up today, so let’s learn a little bit about the sandhill crane and see if it makes any sense as a solution.

The sandhill crane is a big bird. A big male can have a wingspan of almost 8 feet, or 2.3 meters. It’s mostly gray in color and since it has long legs, it can stand 4 ½ feet tall, or 135 cm. In the dark, this might look like a man-sized gray creature with angel wings.

But actually, the sandhill crane theory is nonsense and here’s why. First, sandhill cranes don’t migrate through West Virginia. By mid-November the nearest sandhill cranes are in their wintering grounds in Alabama or Florida, where they congregate in wetlands in the thousands, or on their way to those areas from their breeding grounds in Canada. Second, sandhill cranes are not nocturnal. They’re not active at night at all. They also aren’t clumsy on the ground—quite the opposite, since they’re well known for the elegant dances mated pairs perform. Third, the sandhill crane has a long neck, a small head, and a long bill, very different from the description given of Mothman. I’ve seen sandhill cranes and they’re beautiful birds, but there’s nothing spooky about them.

Other birds were suggested as culprits too, including a Canada goose, an Andean condor, and an oversized green heron. The Andean condor has never been seen in North America and isn’t nocturnal anyway, plus it looks like a gigantic vulture, which it is. The Canada goose is a common, well-known bird that has a long neck but short legs, and isn’t nocturnal. The green heron is a small and humble bird with a wingspan barely more than two feet across, or 68 cm. It has long yellow legs with really big feet and a long, heavy bill.

It’s worth noting that none of the newspaper reports mention a bill, although they do stress that the creature had big eyes that glowed red in the light. The head isn’t prominent either, with one newspaper quoting Roger Scarberry as saying the head was “not an outstanding characteristic.”

By the end of November, newspapers had started calling the creature Mothman more and more, and that’s the name that stuck even though it didn’t actually look like a moth. It did look like another animal, though, and the newspapers even picked up on that by the end of December 1966, when a snowy owl was shot in the area.

The snowy owl is also a large bird, mostly snow-white although young birds have black and gray markings. Its eyes are yellow. Its wingspan can be as much as six feet across, or 1.8 meters. It lives throughout the Arctic and nearby regions and is migratory, sometimes traveling long distances to find food. It mostly eats small animals like lemmings although it will also kill birds, including ducks. It’s rare for one to stray as far south as West Virginia, but the bird killed in December 1966 fits the description of a snowy owl. Its wingspan was almost five feet across, or 1.5 meters.

The newspapers declared that the snowy owl was the culprit behind the mothman sightings. Linda doesn’t agree according to her interview, and I actually don’t either. I do think it’s an owl, just not a snowy owl.

I don’t even think mothman was inspired by a very big owl, like a great horned owl. I think it was a much smaller, more common bird. The barn owl is common throughout much of the world, including West Virginia. Its wingspan is 3.5 feet across at most, or just over one meter.

The reason I think that mothman was a barn owl is because the four people in the car saw several of them around midnight, although they assumed they were seeing the same creature over and over. It’s nocturnal, although it’s also sometimes active at dawn and dusk or even in daytime, and it hunts low over the ground listening for the sound of small animals like mice. Because it flies so low, the barn owl is sometimes hit by cars and would certainly be vulnerable to getting a wing caught in the guide wire of a power pole.

The barn owl has a heart-shaped face that is usually white. Its body is pale underneath and gray or brown above. It doesn’t have ear tufts. Its eyes are large and completely black, but they reflect red at night. It also has an inconspicuous beak with a ridge of feathers at its base that can look like the suggestion of a human-like nose. In other words, it can look superficially like it has a human head and face, especially when seen at night in the glare of headlights, but weird and eerie because it doesn’t quite match up with human features.

One thing people usually don’t realize is that owls actually have quite long legs. An owl standing with its legs extended and its body straight genuinely looks like a tiny, creepy person with wings instead of arms. The male barn owl even shows off his legs and his flying ability in a courtship display called the moth flight, where he hovers in front of a female with his legs dangling.

The gravedigger who supposedly saw a manlike creature with wings fly over him only came forward after the story hit the newspapers. People who doubted it was the same creature because it was seen so far away from the TNT area are assuming Mothman was a single entity when it was probably different birds being seen in different places.

If you’re still doubtful, let’s go back to Linda’s interview that we quoted earlier. She says repeatedly that she thought the creature was scared and she also mentions she felt sorry for it. We can infer several things from these statements. First, Linda is obviously a compassionate person who can feel sorry for a creature even when she’s terrified by it. Second, she must be honest because she hasn’t changed her story to make Mothman seem menacing or dangerous. She seems to be reporting exactly what she remembers seeing and feeling. Third, Mothman does not actually seem to be very big.

When you’re scared, especially if it’s dark, anything threatening or out of place seems larger than it really is, especially when you think back on it. Combine that with most people not knowing that an owl has really long legs and not knowing how huge a big bird’s wings really are when they’re unfolded, and that’s the recipe for a monster story.

Linda does specifically say the creature had huge hands that it was using to pull at its wing. My suggestion is that the owl was standing on one leg, which was extended to its full length because it didn’t want to put any more pressure on its wing than it had to. It was either using its other foot to pull at its wing or, more likely to my mind, to try and grab the guide wire to hoist itself up to a better angle. In addition to having very long legs, owls have huge talons, and in the dark that huge talon would have looked like a human-like hand. With one leg on the ground and one leg stretched up toward its wing, Linda naturally assumed it had the ordinary compliment of two legs and two arms in addition to two wings.

Once the creature freed its wing, it didn’t fly away. Its wing was probably hurt and it ran toward the nearest shelter, an abandoned building. The witnesses said it was a clumsy runner, and that’s true of owls too. Their talons are made for grabbing, not walking on.

Then, a few minutes later, the witnesses saw the creature—or something that looked like it—on a sign as they left the TNT area. I don’t know the size of the sign but even if it was a big sign, would a human-sized creature really perch on it? It flew straight up, which also seems unlikely for a creature as heavy as a human six feet tall. Heavy birds can’t fly straight up, but an owl can because it’s actually not very heavy at all. It looks big because owls have such thick, fluffy feathers.

Later, Linda reports seeing the creature—or, again, something that looked like it—sitting on a wall. She says “It was sitting crouched down, with its arms around its legs and its wings tucked against its back.” This actually sounds like the way an owl usually sits except of course that an owl doesn’t have arms. Linda thought it had arms so she would have assumed they were wrapped around its legs, which is why she couldn’t see them.

Obviously the people who saw the creature were terrified. That’s a natural reaction to seeing something at night that you can’t identify and think might be dangerous and even supernatural. I don’t think any of the initial witnesses were lying or stupid or drunk, or anything like that. They had a frightening encounter they couldn’t understand, and that’s nothing to be ashamed of. Last year I woke up in the middle of the night and heard a little girl’s voice say, “Oh, hello there!” in the darkness of my bedroom in my locked house with no other people in the house with me. It was absolutely terrifying–but then I woke up better and realized that I’d been dreaming and my cat Dracula was snoring, and as I woke up my brain interpreted the little cat snores as a person talking. That doesn’t mean I was stupid and that doesn’t change the fact that I was really scared even after I realized what happened.

The trouble is that many people, after they’ve had a frightening experience like this, refuse to consider that they might have been wrong about what they saw. They say things like, “I know what I saw!” without taking into account that maybe their brain was doing its best to fill in details so they could better evaluate the potential danger. You brain is hard-wired to give you as much information about danger as possible so you can decide whether to run away or prepare to fight or just laugh and tell your little brother he didn’t actually scare you. If you can’t see details properly because it’s dark and the car’s headlights are making weird shadows, your brain fills in the details based on what you can see (and what you expect to see), and it’s not always correct. If in doubt, your brain assumes the thing you’re seeing is dangerous. That’s how our far-distant ancestors survived when movement in tall grass might actually have been a cave bear and not just the wind.

In other words, after a scary experience is over and you’re thinking back about what happened, ask yourself if it’s more likely that you saw a flying man with wings and red eyes, or if you saw an owl and your brain added other details to convince you to run just in case you were in danger.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!