Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:55 — 20.0MB)

Thanks to Pranav for suggesting this week’s topic, animals of the Paleogene, the period after the Cretaceous! Thanks also to Llewelly for suggesting the horned screamer, now one of my favorite birds.

Further watching:

Southern Screamers making noise

Further reading:

Presbyornis looked a lot like a long-legged goose [art by Smokeybjb – CC BY-SA 3.0]

The southern screamer (left) and horned screamer (right), probably the closest living relation to Presbyornis:

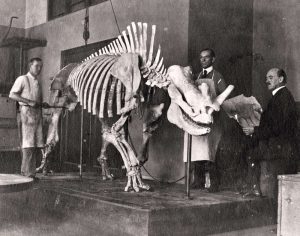

Megacerops was really really big:

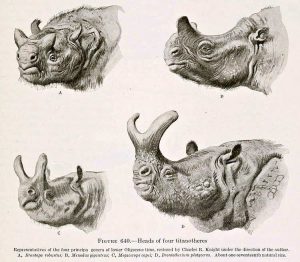

All four of these illustrated animals are actually megacerops, showing the variation across individuals of nose horn size:

Uintatherium had a really weird skull and big fangs:

Pezosiren didn’t look much like its dugong and manatee descendants:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at some strange animals of the Paleogene period, a suggestion from Pranav. Pranav also suggested the naked mole-rat that we talked about in episode 301, but I forgot to credit him in that one.

As we talked about in episode 240, about 66 and a half million years ago, a massive asteroid smashed into the earth and caused an extinction event that ended the era of the dinosaurs. The geologic time period immediately after that event is called the Paleogene, and paleontologists study this era to learn how life rebounded after the extinction event. We’re going to learn about a few animals that evolved to fill ecological niches left vacant after dinosaurs went extinct.

These days, mammals fill a whole lot of these ecological niches, so it’s easy to assume that mammals have been successful for the last 66 million years. But while that’s true now, birds were incredibly successful for a long time. Basically for millions of years after the non-avian dinosaurs died out, it was dinosaurs 2.0 as the avian dinosaurs, better known as birds, spread throughout the world and evolved into some amazing organisms.

This included terror birds, which we talked about in episode 202. They lived in South America, except for one species from North America, and evolved really soon after the dinosaurs went extinct, appearing in the fossil record about 60 million years ago. They lasted a long time, too, only going extinct around 2 million years ago.

The earliest known terror bird was about three feet tall, or 91 cm, but its descendants became larger and more fearsome until they were apex predators throughout South America. The biggest species grew up to ten feet tall, or three meters, with a massive beak and sharp claws on its toes. It couldn’t fly but was a fast runner. You would not want a terror bird chasing you.

Lots of other birds evolved throughout the Paleogene, but most of them would look pretty familiar to us today. Paleontologists have found fossils of the ancestors of many modern birds, including penguins, hummingbirds, and parrots, which shows that they were already specialized some 25 or 35 million years ago or even more. In the case of penguins, we have fossils of penguin ancestors dating back to the late Cretaceous, before the extinction event. Those ancient penguins could probably still fly, but it didn’t take too long to evolve to be a fully aquatic bird. The species Waimanu manneringi lived around 62 million years ago in what is now New Zealand. It resembled a loon in a lot of ways, with its legs set well back on its body, and it probably spent much of its time floating on the water between dives. But unlike a loon, it had lost the ability to fly and its wings were already well adapted to act as flippers underwater.

Another bird would have looked familiar at first glance, but really weird when you gave it a second look. Presbyornis lived between about 62 and 55 million years ago in what is now North America, and it lived in flocks around shallow lakes. It was the size of a swan or goose and mostly shaped like a goose, with a fairly chonky body and a long neck. It had a large, broad duckbill that it used to filter small animals and plant material from the water and its feet were webbed…but its legs were really long, more like a heron’s legs.

When the first Presbyornis fossils were found in the 1920s, the scientists thought they’d found ancient flamingos. But when a skull turned up, Presbyornis was classified with ducks and geese. It wasn’t very closely related to modern ducks and geese, though. Researchers now think its closest modern relation is a South American bird called the screamer. Llewelly suggested the horned screamer a long time ago and now that I have learned more about these birds, I love them so much!

The screamer looks sort of like a goose but has long, strong legs and a sharp bill more like a chicken’s. It lives in marshy areas and eats pretty much anything, although it prefers plant material. It has two curved spurs that grow on its wings that it uses to defend its territory from predators or other screamers, and if a spur breaks off, which it does pretty often, it grows back. The screamer mates for life and both parents build the nest together and help take care of the eggs and chicks when they hatch.

The horned screamer has a long, thin structure that grows from its forehead and looks sort of like a horn, although it’s not a horn. It’s wobbly, for one thing, but it’s also not a wattle. It grows throughout the bird’s life and may break off at the end every so often, and it’s basically unlike anything seen in any other bird. Maybe presbyornis had something similar, who knows?

The screamer gets its name from its habit of screaming if it feels threatened or if it just encounters something new or that it doesn’t like. The screaming is actually more of a honking call that sounds like this:

[screamer call]

People sometimes raise screamers with chickens to act as guard birds. It can run fast but it can swim faster, and it can also fly although it doesn’t do so very often. Although it’s distantly related to ducks, its meat is spongy and full of air sacs that help keep it afloat in the water, so people don’t eat it. It is vulnerable to habitat loss, though.

One organism that evolved early in the Paleogene was grass. You know, the plant that a whole lot of animals eat. There are lots and lots of different types of grass, not just the kind we’re used to mowing, and as the Paleogene progressed, it became more and more widespread. But it wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is now, so even though the ancestors of modern grazing animals evolved around the same time, they weren’t grazers yet. The word graze comes from the word grass, but ancient ancestors of horses and other grazing animals were still browsers. They ate all kinds of plants, and didn’t specialize as grazers until grasses really took off and huge grasslands developed in many parts of the world, around 34 million years ago.

Because the Paleogene lasted so long, between about 66 and 23 million years ago, there’s literally no way we can talk about more than a few animals that lived during that time, not in a single 15-minute episode. We’ve also covered a lot of Paleogene animals in previous episodes, like paraceratherium in episode 50, the largest land mammal known. It probably grew up to about 16 feet tall at the shoulder, or 5 meters, and taller if you measured it at the top of its head. Other examples are moeritherium, an ancient elephant relation we talked about in episode 18, the giant ground sloth that we talked about in episode 22, and the ancient whale relation basilosaurus that we talked about in episode 132. Patrons also got a bonus basilosaurid episode this month. But I’m pretty sure we’ve never talked about brontotheres.

Brontotheres first appear in the fossil record around 56 million years ago and they lived until at least 34 million years ago. All animals in the family Brontotheriidae are extinct, but they were closely related to horses. They didn’t look like horses, though; they looked a lot like weird rhinoceroses, although remember that rhinos are also related to horses. They were members of the odd-toed ungulates, along with tapirs and the gigantic Paraceratherium.

Fossil remains of brontotheres have been found in North America, a few parts of eastern Europe, and Asia, although they might have been even more widespread. The earliest species were only about three and a half feet tall at the shoulder, or about a meter, but later species were much larger. While they looked a lot like rhinos, they didn’t have the kind of keratin hose horns that rhinos have. Instead, some species had a pair of horns made of bone that varied in shape and size depending on species. The horns were on the nose as in rhinos, but were side-by-side.

Brontotheres developed before grasslands became widespread, and instead they were browsers that mostly ate relatively soft vegetation like leaves and fruit. Grass is really tough and animals had to evolve specifically to be able to chew and digest it. In fact, the rise of grasslands as the climate became overall much drier around 34 million years ago is probably what drove the brontotheres to extinction. They lived in semi-tropical forests and probably occupied the same ecological niche that elephants do today. This was before elephants and their relations had evolved to be really big, and brontotheres were the biggest browsing animals of their time.

Brontotheres probably lived in herds or groups of some kind. They were widespread and common enough that they left lots of fossils, so many that they were found relatively often in North America even before people knew what fossils were. The Sioux Nation people were familiar with the bones and called them thunder horses. When they were scientifically described in 1873 by Othniel Marsh, he named them after the Sioux term, since brontotherium means “thunder beast.”

Two of the biggest brontotheres lived at about the same time as each other, around 37 to 34 million years ago. Megacerops lived in North America while Embolotherium lived in Asia, specifically in what is now Mongolia. Megacerops is the same animal that’s sometimes called brontotherium or titanotherium in older articles and books.

Megacerops and Embolotherium were about the same size, and they were huge, although Embolotherium was probably just a bit larger than Megacerops. They stood over 8 feet tall at the shoulder, or 2.5 meters, and were more than 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters. This is much larger than any rhinos alive today and as big as some elephants. Their legs would probably have looked more like an elephant’s legs than a rhinoceros’s.

Brontothere nose horns weren’t true horns, since they don’t seem to have been covered with a keratin sheath, but they were formed from protrusions of the nasal bones. They might have been more like ossicones, covered with skin and hair. Megacerops had a pair of nose horns that were much larger in some individuals than others, and scientists hypothesize that males had the larger horns and used them to fight each other.

But this can’t have been the case for embolotherium. It had even bigger nose horns that were fused together in a wedge-shaped plate sometimes referred to as a ram, but they contained empty chambers inside that were a continuation of the nasal cavities. They wouldn’t have been strong enough to bash other embolotheriums with, but they might have acted as resonating chambers, allowing embolotherium to communicate with loud sounds. All individuals had these nose horns, even juveniles, and they were all about the same size, which further suggests that they had a purpose unrelated to fighting.

At about the same time the brontotheres were evolving, another big browsing animal also lived in what are now China and the United States. Two species are known, one in each country, and both stood about 5 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.5 meters. It looked sort of like a brontothere in some ways, but very different in other ways, especially its weird skull, and anyway it was already big around 56 million years ago when brontotheres were still small and unspecialized.

Scientists aren’t sure what uintatherium was related to. It’s been placed in its own genus, family, and order, although some other uintatherium relations have been discovered that share its weird traits. Most scientists these days think it was probably an ungulate.

Uintatherium’s skull was extremely strong and thick, which didn’t leave a whole lot of room for brains. But what uintatherium lacked in brainpower, it made up for in sheer defensive ability. It had huge canine teeth that hung down like a sabertooth cat’s fangs, although males had larger fangs than females. Males also had three pairs of ossicones or horns on the top of the skull that pointed upwards. One pair was on the nose, one pair over the eyes, and one pair almost on the back of the skull. They could be as much as 10 inches long, or 25 cm, and paleontologists think that males wrestled with these horns the same way male deer will lock antlers and wrestle.

Uintatherium lived in the same habitat and probably ate more or less the same type of plants that later brontotheres did. They went extinct around the time that brontotheres evolved to be much larger, which suggests that brontotheres may have outcompeted uintatherium.

We’ll finish with one more Paleogene mammal, Pezosiren. It was only described in 2001 from several incomplete specimens discovered in Jamaica in the 1990s, and it lived between 49 and 46 million years ago.

Pezosiren was about the size of a pig, although it had a longer, thicker tail compared to pigs. It wasn’t any kind of pig, though, and in fact it was distantly related to elephants. It was the oldest known ancestor of modern sirenians. Pezosiren is also called the walking siren, because it still had four legs and probably spent at least part of the time on land, although it could swim well. Scientists think it probably swam more like an otter than a sirenian, propelling itself through the water with its hind legs instead of its tail.

Pezosiren was probably semi-aquatic, sort of like modern hippos, and already shows some details specific to sirenians, especially its heavy ribs that would help it stay submerged when it wanted to. It ate water plants and probably stayed in shallow coastal water. At different times in the past, Jamaica was connected to the North American mainland or was an island on its own as it is now, or occasionally it was completely submerged. About 46 million years ago it submerged as sea levels rose, and that was the end of Pezosiren as far as we know. But obviously Pezosiren either survived in other areas or had already given rise to an even more aquatic sirenian ancestor, because while Pezosiren is the only sirenian known that could walk, its descendants were well adapted to the water. They survive today as dugongs and manatees.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!