Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:07 — 15.4MB)

This week we’ll learn about a fascinating parrot and some more weird praying mantises! Thanks to Page and Viola for the suggestions!

Further watching:

Nova Science Now: Irene Pepperberg and Alex

Alex: Number Comprehension by a Grey Parrot

The Smartest Parrots in the World

Further reading:

Ancient mantis-man petroglyph discovered in Iran

Alex and Irene Pepperberg (photo taken from the “Why do parrots talk?” article above):

Two African grey parrots:

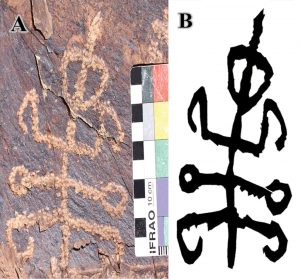

The “mantis man” petroglyph:

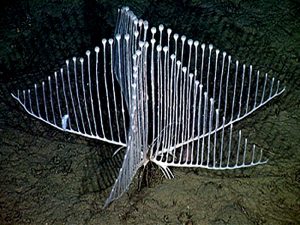

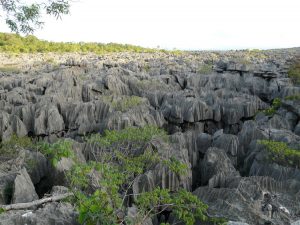

The conehead mantis is even weirder than “ordinary” mantis species:

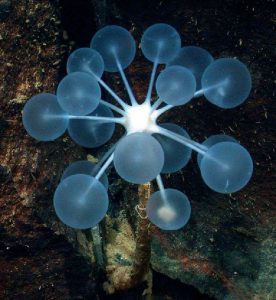

Where does Empusa fasciata begin and the flower end (photo by Mehmet Karaca)?

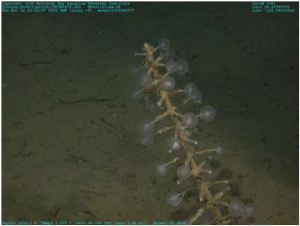

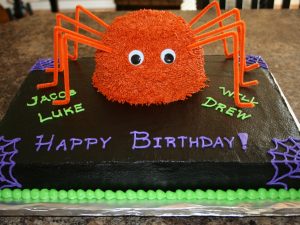

The beautiful spiny flower mantis:

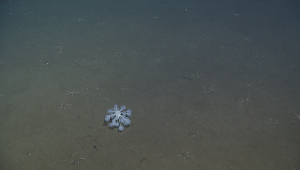

The ghost mantis looks not like a ghost but a dead leaf:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at two completely unrelated animals, but both are really interesting. Thanks to Page and Viola for the suggestions!

We’ll start with Page’s suggestion, the African gray parrot. We haven’t talked about very many parrots in previous episodes, even though parrots are awesome. The African gray parrot is from Africa, and it’s mostly gray, and it is a parrot. Specifically it’s from what’s called equatorial Africa, which means it lives in the middle of the continent nearest the equator, in rainforests. It has a wingspan of up to 20 inches, or 52 cm, and it has red tail feathers.

The African gray parrot is a popular pet because it’s really good at learning how to talk. It doesn’t just imitate speech, it imitates various noises it hears too. It’s also one of the most intelligent parrots known. Some studies indicate it may have the same cognitive abilities as a five year old child, including the ability to do simple addition. It will also give its treats to other parrots it likes even if it has to go without a treat as a result, and it will share food with other parrots it doesn’t even know.

Despite all the studies about the African grey in captivity, we don’t know much about it in the wild. Like other parrots, it’s a highly social bird. It mostly eats fruit, seeds, and nuts, but will also eat some insects, snails, flowers, and other plant parts. It mates for life and builds its nest in a tree cavity. Both parents help feed the babies. That’s basically all we know.

It’s endangered in the wild due to habitat loss, hunting, and capture for sale as pets, so if you want to adopt an African grey parrot, make sure you buy from a reputable parrot breeder who doesn’t buy wild birds. For every wild parrot that’s sold as a pet, probably a dozen died after being taken from the wild. A good breeder will also only sell healthy birds, and will make sure you understand how to properly take care of a parrot. Since the African grey can live to be up to sixty years old, ideally it will be your buddy for basically the rest of your life, but it will require a lot of interaction and care to stay happy and healthy.

One African grey parrot named Alex was famous for his ability to speak. Animal psychologist Dr. Irene Pepperberg bought Alex at a pet shop in 1977 when he was about one year old, not just because she thought parrots were neat and wanted a pet parrot, but because she wanted to study language ability in parrots.

Pepperberg taught Alex to speak and to perform simple tasks to assess his cognitive abilities. Back then, scientists didn’t realize parrots and other birds were intelligent. They thought an animal needed a specific set of traits to display intelligence, such as a big brain and hands. You know, things that humans and apes have, but most animals don’t. Pepperberg’s studies of Alex and other parrots proved that intelligence isn’t limited to animals that are similar to us.

Alex had a vocabulary of about 100 words, which is average for a parrot, but instead of just mimicking sounds, he seemed to understand what the words meant. He even combined words in new ways. He combined the words banana and cherry into the word banerry to describe an apple. He didn’t know the word for cake, so when someone brought a birthday cake into the lab and he got to taste it, he called it yummy bread. When he saw himself in a mirror for the first time, he said, “What color?” because he didn’t know the word gray. He also asked questions about new items he saw. So not only did he understand what words meant, he actually used them to communicate with humans. As Pepperberg explains, Alex wasn’t super-intelligent or unusual for a parrot. He was just an ordinary parrot, but was trained properly so he could express in words the intelligence that an average parrot uses every day to find food and live in a social environment.

Alex died unexpectedly in 2007 at only 31 years old. I’ve put a link in the show notes to a really lovely Nova Science Now segment about Alex and Dr. Pepperberg, and some other videos of Alex and other parrots. Pepperberg has continued to work with other parrots to continue her studies of language and intelligence in birds.

This is audio of Alex speaking with Pepperberg. You’ll notice that he sounds like a parrot version of her, which is natural since he learned to speak by mimicking her voice, meaning they have the same intonations and pronunciations.

[Alex the parrot speaking with his trainer, Dr. Pepperberg]

Next, Viola wants to learn about praying mantises. We had an episode about them not too long ago, episode 187, but there are more than 2,400 known species, so many that we could have hundreds of praying mantis episodes without running out of new ones to talk about.

Today we’ll start somewhere I bet you didn’t expect, an ancient rock carving from central Iran.

The carving was discovered while archaeologists were surveying the region in 2017 and 2018. I’ll put a picture of it in the show notes, but when you first look at it, you might think it was a drawing of a plant or just a decoration. I’ll try to describe it. There’s a central line that goes up and down like a stick, with three lines crossing the central line and a rounded triangle near the top. The three lines have decorations on each end too. The bottom line curls downward at the ends, the middle line ends in a little circle at each end, and the top line curves up and then down again at the ends. It’s 5 1/2 inches tall, or 14 cm, and a little over four inches across at the widest, or 11 cm. Archaeologists have estimated its age as somewhere between 4,000 years old and 40,000 years old. Hopefully they’ll be able to narrow this age range down further in the future.

The team that found the carving, which is properly called a petroglyph, was actually looking specifically for petroglyphs that represented invertebrates. So instead of thinking, “Oh, that’s just a tree” or “I don’t know what that is, therefore it must just be a random doodle,” the archaeologists thought, “Bingo, we have a six-legged figure with a triangular head and front legs that form hooks. It looks a lot like some kind of praying mantis.”

But while archaeologists might know a lot about petroglyphs, they’re not experts about insects, so the archaeologists asked some entomologists for help. They wanted to know what kind of praying mantis the carving might depict.

The entomologists thought it looked most like a mantis in the genus Empusa, and several species of Empusa live in or near the area, although they’re more common in Africa. So let’s talk about a few Empusa species first.

The conehead mantis is in the genus Empusa and is native to parts of northern Africa and southern Europe. Like most mantises, females are larger than males, and a big female conehead mantis can grow up to four inches long, or 10 cm. The body is thin and sticklike, with long, thin legs, and individuals may be green, brown, or pink to blend in among the shrubs and other low-growing plants where it lives. It eats insects, especially flies. So far this is all pretty normal for a praying mantis. But the conehead mantis has a projection at the back of the head that sticks almost straight up. It’s called a crown extension and it helps camouflage it among sticks and twigs. It also often carries its abdomen so that it curves upward.

Other members of the genus Empusa share these weird characteristics with the conehead mantis. Empusa fasciata lives in parts of western Asia to northeastern Italy and is usually green and pink with lobe-shaped projections on its legs that help it blend in with leaves and flowers. It mostly eats bees and flies, and females spend a lot of time waiting on flowers for a bee to visit. And then you know what it does…CHOMP. The more I learn about insects that live on flowers, the more I sympathize with bees. Everything wants to eat bees. E. fasciata also has a crown extension that makes its head look like a knob on a twig, and it also sometimes carries its abdomen curved sharply upward so that it looks a lot like a little spray of flowers.

Most mantids are well camouflaged. We talked about the orchid mantis in episode 187, which mimics flowers the same way E. fasciata does. But a few mantis species look like they should really stand out instead of blending in, at least to human sensibilities. The spiny flower mantis is white with green or orange stripes on its legs and a circular green, yellow, and black pattern on its wings. When I first saw a photo of it, I honestly thought someone had photoshopped the wing pattern on. But if something threatens a spiny flower mantis, it opens its wings in a threat display, and the swirling circular pattern suddenly looks like two big eyes. It also honestly looks like really nifty modern art. I really like this mantis, and you know I am not fond of insects so that’s saying something. It lives in sub-Saharan Africa and females grow about two inches long, or 5 cm.

Finally, the ghost mantis is really not very well named because it doesn’t look anything like a ghost, unless a ghost looks like a dead leaf. It looks so much like a leaf that it should be called a leaf mantis, but there are actually lots of different species called leaf mantis or dead leaf mantis. This particular one is Phyllocrania paradoxa, and it also grows to about two inches long, or 5 cm. It lives in Africa and most individuals are brown, although some are green or tan depending on the humidity level where it lives. It looks exactly like a dead leaf that’s sort of curled up, except that this leaf has legs and eats moths and flies. It even has a crown extension that looks like the stem of a leaf. Unlike most mantis species, it’s actually pretty timid and less aggressive toward members of its own species. In other words, ghost mantises are less likely to eat each other than most mantis species are.

People keep all these mantises as pets, which I personally think is weird but that’s fine. They’re easier to take care of than parrots are, although you’ll never manage to teach a praying mantis to talk.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!