Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:25 — 11.7MB)

Thanks to Jayson for suggesting this week’s topic, the new “dire wolf”! Also, possibly the same but maybe a different Jayson is the youngest member of the Cedar Springs Homeschool Science Olympiad Team, who are on their way to the Science Olympiad Nationals! They’re almost to their funding goal if you can help out.

Further reading:

Dire wolves and woolly mammoths: Why scientists are worried about de-extinction

The story of dire wolves goes beyond de-extinction

These fluffy white wolves explain everything wrong with bringing back extinct animals

Dire Wolves Split from Living Canids 5.7 Million Years Ago: Study

“Dire wolf” puppies:

An artist’s interpretation of the dire wolf (red coats) and grey wolves (grey coats) [taken from fourth link above]:

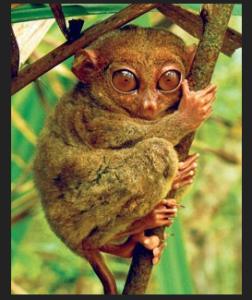

The “mammoth fur” mice:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have a suggestion from Jayson, who wants to learn about the so-called “new” dire wolf.

Before we get started, a big shout-out to another Jayson, or maybe the same one I’m honestly not sure, who is the youngest member of the Cedar Springs Homeschool Science Olympiad Team. They’ve advanced to the nationals! There’s a link in the show notes if you want to donate a little to help them with their travel expenses. This is a local team to me so I’m especially proud of them, and not to brag, but I’ve actually met Jayson and his sister and they’re both smart, awesome kids.

Now, let’s find out about this new dire wolf that was announced last month. In early April 2025, a biotech company called Colossal Biosciences made the extraordinary claim that they had produced three dire wolf puppies. Since dire wolves went extinct around 13,000 years ago, this is a really big deal.

Before we get into the details of Colossal’s claim, let’s refresh our memory about the dire wolf. We talked about it in episode 207, so I’ve taken a lot of my information from that episode.

According to a 2021 study published in Nature, 5.7 million years ago, the shared ancestor of dire wolves and many other canids lived in Eurasia. Sea levels were low enough that the Bering land bridge, also called Beringia, connected the very eastern part of Asia to the very western part of North America. One population of this canid migrated into North America while the rest of the population stayed in Asia. The two populations evolved separately until the North American population developed into what we now call dire wolves. Meanwhile, the Eurasian population developed into many of the modern species we know today, and some of those eventually migrated into North America too.

By the time the gray wolf and coyote populated North America, a little over one million years ago, the dire wolf was so distantly related to it that even when their territories overlapped, the species avoided each other and didn’t interbreed. We’ve talked about canids in many previous episodes, including how readily they interbreed with each other, so for the dire wolf to remain genetically isolated, it was obviously not closely related at all to other canids at that point.

The dire wolf looked a lot like a grey wolf, but researchers now think that was due more to convergent evolution than to its relationship with wolves. Both lived in the same habitats: plains, grasslands, and forests. The dire wolf was slightly taller on average than the modern grey wolf, which can grow a little over three feet tall at the shoulder, or 97 cm, but it was much heavier and more solidly built. It wouldn’t have been able to run nearly as fast, but it could attack and kill larger animals.

The dire wolf went extinct around 13,000 years ago, but Colossal now claims that they’re no longer extinct. There are now exactly three dire wolves in the world, two males and a female, born to two different dogs who acted as surrogate mothers. But are these really dire wolves, or are they something else?

Colossal’s scientists claim that the 2021 Nature study that determined gray wolves and dire wolves weren’t closely related and couldn’t interbreed was based on poor-quality DNA studies. They redid the genetic scans and determined that dire wolves were more wolf-like than the 2021 study thought. But the 2021 study was published in the foremost peer-reviewed journal in the scientific world. Colossal’s study hasn’t been published at all.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. In other words, until a study is published in a respected peer-reviewed journal that contradicts the 2021 Nature study, all the genetic evidence we have now points to dire wolves and gray wolves being extremely genetically different.

Colossal’s scientists made 20 edits to 14 gray wolf genes to make the puppies more similar to dire wolves in size, with white coats even though there’s no evidence that real dire wolves were white. Colossal claims that the genomes of grey wolves and dire wolves are 99.5% identical, but those 20 changes are out of 12,235,000 genetic differences. Genetically these puppies are just modern grey wolves.

The biggest problem with the claim that the puppies are actually dire wolves is that it implies that bringing back an extinct species is really easy. Not only can this make people think that extinction isn’t a big deal after all, it also ignores the issues that make animals go extinct in the first place, especially recently, like pollution, habitat loss, climate change, invasive species, and over-hunting or capture of wild animals to sell as exotic pets.

In the very first, very terrible Strange Animals Podcast episode, I talked about the quagga, a species of zebra from South Africa that went extinct very recently due to human causes. I was excited about the de-extinction attempts for that species, which mostly involved breeding zebras with the most quagga genetic material to select for quagga-like traits. I still think this is a good project, since the quagga’s ecosystem is still in place and still has a quagga-shaped hole in it. Colossal has also done good work with red wolves in North America, helping to keep that critically endangered species genetically healthy.

Also in an early episode, I talked about Colossal’s de-extinction plans for the mammoth. I was all for that too, tongue-in-cheek, because I said I wanted a pet mammoth. Now I’ve changed my mind. Awesome as it would be to see real live mammoths, there’s not any real habitat left for them. Between climate change, habitat loss due to human activity, and more than ten thousand years of evolution of other animals to move into the mammoth’s empty ecological niche, where does Colossal plan to put its mammoths? We don’t even have safe habitats for elephants anymore, which are still around.

Earlier this year, Colossal announced another genetically modified animal, mice with long golden-brown fur inspired by woolly mammoth fur. Mammoths were highly adapted for cold far beyond long fur, while modern elephants are highly adapted for hot climates. If Colossal’s mammoths are anything like its so-called dire wolves, they’ll be editing genes to change appearance, not anything else. That’s unethical, basically taking an endangered heat-adapted animal, giving it a heavy coat, and sticking it into a cold climate. It will have no herd mates and no knowledge of how to survive in the wild in a climate it was never intended to live in, meaning it will be dependent on human help. Once the novelty of “oh look, a furry elephant” wears off, and Colossal either goes out of business or moves on to the next big thing, what will happen to the mammoth?

That’s one of the concerns about the new dire wolves. They don’t have a wolf family. They’re completely dependent on humans and will never be able to survive in the wild, even if they were allowed to try.

Let’s return to extinct canids to finish on a brighter note, something that Richard from NC brought to my attention recently. It’s an animal called epicyon, a canid that may have lived as recently as 5 million years ago in North America. It’s the largest canid ever discovered, around 3 feet tall, or 90 cm, at the shoulder and as much as 8 feet long, or 2.5 meters. It probably weighed as much as a small bear, and it was strong and powerful so that it was probably more bear-like or lion-like in body shape than wolf-like.

It had a short, powerful muzzle and strong jaws with huge teeth meant for crushing bone, similar to modern hyenas. It wasn’t anywhere near as fast a runner as modern wolves, but it could probably move pretty fast when it needed to. Some scientists think it was a pack animal, but it may have been an ambush predator instead of hunting in packs like wolves and other modern canids do.

Epicyon probably preyed on megaherbivores like camels, horses, pronghorn, rhinoceroses, and peccaries, all of which were common in North America several million years ago. It probably also scavenged a lot of its food, since it could break bones other animals couldn’t. We’re not sure why epicyon went extinct, but some scientists suggest it was out-competed by saber-tooth cats and more modern canids–including the dire wolf.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!