Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:56 — 12.5MB)

This week we’re back to Sumatra, that island of mystery, to learn about a mysterious ape called the orang pendek.

A beautiful Sumatran orangutan:

This orangutan and her baby have won all the bananas:

This picture made me DIE:

An especially dapper siamang, a type of gibbon:

Here’s a walking siamang:

The sun bear, looking snoozy:

The sun bear, standing:

Further reading:

These are the articles where I got my quotes.

This one has some general information.

This one is by Debbie Martyr herself.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

The island of Sumatra is a place that keeps popping up in our episodes. We’ve barely scratched the surface of weirdness in Sumatra and nearby islands, but this week’s episode is about a Sumatran mystery ape called the orang pendek. That means “short person” in Indonesian.

The story goes that a human-like ape lives in the forests of western Sumatra. It walks on two legs, has short black, gray, or golden fur on its body with longer hair on its head, human facial features, and is shorter than a human but not by much. The people of the remote Sumatran villages where the orang pendek is reported say that it’s enormously strong, and has small feet and short legs but long arms. It mostly eats plants and will raid crops occasionally, but it also eats insects, fish, and river crabs.

Many people think the first report of the orang pendek outside of the Sumatran people is from a 14th century traveler called John of Florence, who visited China around 1342 and many other countries afterwards, including either Java or Sumatra. He reported seeing hairy men who lived on the edges of the forest, but since he also said that the hairy men planted crops and traded with the locals, it’s possible he was talking about a tribe of people who lived on the outskirts of mainstream society.

The various native groups in Sumatra have stories of creatures that sound like the orang pendek, including a demon-like entity called the hantu pendek, which means short ghost. But as I’ve said before in other episodes, it’s a mistake to treat folktales as if they were scientific observations. People tell stories for lots of reasons, only one of which is imparting knowledge about a particular animal. Plus, those aren’t the only stories of strange people told in the area. There are stories of giants, of people with tails, and many others. For instance, the orang bati is a bat-winged man that’s supposed to live in extinct volcanic craters in Seram, Indonesia, and who flies out at night and steals babies.

The Dutch colonized Indonesia in the early 19th century, around 1820, after centuries of varying levels of control in what was known as the Dutch East Indies. Colonists reported seeing apes or strange small people in the forest too. One fairly typical report is this one from 1917, from a Mr. Oostingh, who saw what he took to be a man sitting on the ground in the forest about 30 feet away from him, or nine meters. He said,

“His body was as large as a medium-sized native’s and he had thick square shoulders, not sloping at all. The colour was not brown, but looked like black earth, a sort of dusty black, more grey than black.

“He clearly noticed my presence. He did not so much as turn his head, but stood up on his feet: he seemed quite as tall as I. Then I saw that it was not a man, and I started back, for I was not armed. The creature took several paces, without the least haste, and then, with his ludicrously long arm, grasped a sapling, which threatened to break under his weight, and quietly sprang into a tree, swinging in great leaps alternately to right and to left.”

Expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s found nothing out of the ordinary. Interest trailed off until around 1990, when a journalist named Debbie Martyr decided she was going to get to the bottom of the mystery. She had traveled to Sumatra in 1989 for a story she was writing, and while she was there she learned about the orang pendek. She spent the next fifteen-odd years interviewing witnesses and setting up camera traps, but without uncovering any proof. She did spot what she thought might be an orang pendek at least once, but got no clear photos, no remains, no conclusive footprints. Martyr states that the ape she saw had much different proportions than an orangutan, much more human-like.

Other people have searched for the orang pendek too, also without success. National Geographic set up camera traps between 2005 and 2009 without getting any photos of unknown apes. One expedition found some hairs that they later sent for DNA testing, but the results were inconclusive due to the hairs’ poor quality and possible human contamination.

Interest in the orang pendek spiked after remains of the Flores little people were found in 2003, and after anthropologists made connections between those remains and local stories about small, mischievous people called the ebo gogo. As you may remember if you’ve listened to episode 26, researchers initially thought the Homo floresiensis remains were only some 12,000 years old. More recent studies have pushed this back to around 50,000 years old. But the island of Flores is not all that far from the island of Sumatra, so it’s not out of the question that the Flores little people also lived on other islands.

Sumatra is a big island with a lot of animal and plant species found nowhere else in the world. It’s certainly a big enough island to hide a population of shy apes or small human relations. But the only proof we have that the orang pendek exists, after a couple of decades of intensive searching, are a bunch of witness reports, some blurry photos and video, inconclusive plaster casts of footprints, and some ape hairs too degraded for DNA testing. If the orang pendek was a real animal, no matter how elusive, you’d think we’d at least have one good clear photo by now.

There have been hoaxes in the past. A “young orang pendek” turned out to be a dead langur monkey with its tail cut off. A video released in 2017 that purports to show a group of motorbikers who startle an orang pendek is probably a hoax. I’ve sent an alert to Captain Disillusion. If he covers the video I’ll let y’all know.

Despite the hoaxes and the lack of evidence, people are obviously seeing something. Witnesses include forest rangers, zoologists, hunters, and other people who know the local animals well. So what could they be seeing? Let’s take a look at some of the animals of Sumatra that might be mistaken for an orang pendek, at least some of the time.

The orang pendek is supposed to have small feet, about the size and shape of a human child’s foot. This sounds like the tracks of the Malayan sun bear. In fact, a footprint found in 1924 that was supposed to belong to an orang pendek was identified as that of a sun bear once it was seen by an expert.

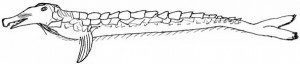

The sun bear has sleek black fur, although some are gray or reddish, and a roughly U-shaped patch of fur on its chest that varies in color from gold to almost white to reddish-orange. Its muzzle is short and its ears are small. It’s the world’s smallest bear, only around three feet long from head to tail, or 150 cm, and four feet tall when standing on its hind legs, or 1.2 meters. It has long front claws that it uses to climb trees and tear open logs to get at insect larvae, which it licks up with its long tongue. It also eats a lot of plant material, especially fruit. It’s mostly nocturnal.

Orangutans also live on the island, but currently only in the northern part of the island, although they lived all over Sumatra and in Java until the end of the 19th century. The Sumatran orangutan is one of only three orangutan species in the world, and is critically endangered due to habitat loss. It’s slenderer than the other species, with pale orange fur. Like the sun bear, it eats a lot of insects and fruit; unlike the sun bear, it uses tools it makes from sticks to gather insects, honey, and other foods more easily. It also uses large leaves as umbrellas. It communicates not by sound, like other orangutans, but by gestures. In short, it sounds like a pretty awesome ape. Orangutan means “forest person,” if you were wondering.

Other apes and monkeys live on the island too, including several species of gibbon. Gibbons are apes, but they’re not considered great apes, only lesser apes. They look more like monkeys, although they don’t have tails. They’re also fairly small, generally about two feet long, or 60 cm, and quite slender. They live in the treetops and swing from branch to branch, which is called brachiation. Orangutans brachiate sometimes too, but they’re much heavier than gibbons and move much more slowly and cautiously. Gibbons can move. They also have loud voices and melodic calls.

The Siamang, a type of gibbon, has a throat pouch called a gular sac which, when inflated with air, enhances the voice and helps it resonate. Family groups of siamangs sing together. The siamang has shaggy black fur and is a little larger than other gibbons, around 3 feet tall, or one meter. Its arms are long, its legs short, and it mostly eats plants, especially fruit, although it also eats insects. Like orangutans and many other animals on Sumatra, it’s threatened by habitat loss.

There’s one thing that the sun bear, the orangutan, and the siamang all sometimes do that is suggestive of the orang pendek. All three sometimes walk on their hind legs. Bears usually only stand on their hind legs to get a better view of something, but they can certainly walk on their hind legs if they want to. While the orangutans of Sumatra spend most of their time in trees, since the Sumatran tiger likes to eat orangutans, it can and does come down to the ground sometimes. Males in particular sometimes walk upright for short distances. Siamangs walk upright along branches, and occasionally on the ground, usually with their long arms held above their heads for balance but not always.

So we have three animals that when seen clearly, really don’t look much like the orang pendek is supposed to look. None have especially human faces, although I’ve just spent half an hour looking at pictures of orangutans and siamangs, and those are some handsome apes. But they all have a number of features that sound like orang pendek features. They’re all the right size, they can all walk upright, their fur is black, gray, or golden, and they eat the things the orang pendek is supposed to eat.

At least some orang pendek sightings are mistaken identity of these three animals, I guarantee it. Even the most knowledgeable zoologist or forest ranger can make a mistake, especially if they only catch a glimpse of the animal or see it in poor light. And, as I often point out, people tend to see what they expect to see. In a 1993 article, Debbie Martyr herself says that when she first started studying the orang pendek sightings, people in Sumatra laughed at the thought that the orang pendek was a real animal. But, she writes, “Times have changed in Sumatra. The officials of the Kerinci Seblat have become, if not converts to the orang pendek cause, then at least openly curious about the animal. Pak Mega Harianto, director of the park, admitted, ‘We now have too many sightings, from all over the national park. It is always the same animal. Always the same description.’”

In other words, as the legend becomes more and more popular, more and more people report seeing a mystery animal that fits the orang pendek’s description. And yet, there is no more proof now than there was in 1925 of the animal’s existence.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t an unknown ape living in Sumatra, of course. I just don’t think that’s what people are seeing. It would be fantastic if the orang pendek did turn out to be a real animal. It would focus more attention on the loss of rainforest and other habitats in Sumatra, and would probably bring more tourists to the island, which would help the local economy. But until someone actually finds a body or captures a live orang pendek, I have to remain skeptical.

I’m sure we’ll revisit Sumatra and other parts of the Malay Archipelago soon to learn about other little-known and mystery animals. Until then, remember that you now know at least one word of the Indonesian language. ‘Orang’ means person, whether it’s an ape-type person or a ghost-type person.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!