Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:04 — 15.7MB)

Thanks to Leo for suggesting this week’s topic, the ponies of Assateague Island!

Further reading:

Some ponies running free on Assateague Island [photo taken from the site linked above]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about the feral horses of Assateague! Thanks to Leo for the suggestion! That’s the grown-up Leo; we also have a young Leo who’s sent some great suggestions, including one we’re hopefully going to get to pretty soon.

Before we talk about Assateague ponies, though, we need to start somewhere else. The kelpie is a Scottish water spirit that’s supposed to appear as a pony wandering by itself, but if someone tries to catch the pony or get on its back to ride it, suddenly it drags the person into the water and either drowns them or eats them. It’s said that the only way to tell that the pony isn’t really a pony is to examine its feet. A real pony has hooves, but a kelpie has claws.

The story comes from the olden days when it was common to see ponies wandering around loose in Scotland and other parts of the UK. Some of the ponies in these areas were semi-feral, meaning they lived a lot of the time like wild animals. Some ponies were kept in stables and farmyards as working animals, but others were allowed to roam around and feed themselves as they liked. Every so often the wild ponies would be rounded up and any young ones branded by their mother’s owner. Sometimes the owner would need another pony to pull a cart or something, and they’d catch one of their ponies and bring it home to train. Sometimes the owner needed money so would catch some of their ponies to sell. The ponies that lived this way had to be tough and hardy to survive almost without human care, but luckily ponies are famously tough.

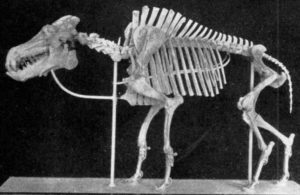

Ponies are a type of small horse, but they’re still horses. They’re generally sturdy, with a thicker coat than a full-sized horse, and usually stand around 14 hands high at the withers at most. The withers is the little bump of shoulder at the base of a horse’s neck, and the horse’s back starts behind the withers. A hand is an old horse measurement that has been standardized to four inches, or just over 10 cm, roughly the width of an adult person’s hand. 14 hands is equivalent to about 4 and a half feet tall, or 1.4 meters.

One of the best-known pony breeds is the Shetland pony, which also happens to be one of the smallest. It only stands 42 inches tall at most, or 107 cm. That’s about 3 and a half feet tall. It’s mostly used as a child’s mount but originally the Shetland was used to pull carts and plows and carry heavy loads, since despite its small size the Shetland pony is incredibly strong.

The Shetland comes from the Shetland Isles off the northeastern coast of Scotland, where it’s lived for at least two thousand years and probably more like 3,000. The islands get very cold in winter and there isn’t a lot of food, so over time the ponies evolved to be small and tough to survive.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, there are feral horses living on an island called Assateague. Assateague Island is off the eastern coast of the United States, closest to the states of Virginia and Maryland. They’re actually not technically ponies except that they’re small, since ponies actually share certain traits that differentiate them from horses, even though these differences aren’t enough to call ponies a subspecies of horse. But because the Assateague horses rarely grow taller than 4 and a half feet tall, or 140 cm, people call them ponies.

I’m going to stop here and tell you a personal story, because I’ve actually seen the Assateague ponies myself. I lived in Pennsylvania for a little while after I finished grad school, and at the time I had an awesome dog named Jasper, a Newfoundland I got through Newf rescue. Newfies are bred to be water dogs in the harsh coastal regions of Newfoundland, Canada, but Jasper had never seen the ocean. I knew he didn’t know or care, but it mattered to me that he got to experience the ocean at least once in his life. I had also wanted to see the Assateague ponies since I was a little girl and read Misty of Chincoteague and its sequels approximately 10,000 times, books by Marguerite Henry.

So I planned a trip to Assateague Island, which is a wildlife refuge these days. I decided to go over a weekend in October, when it wouldn’t be crowded. At the time I was working in a sales office while I tried to find a job I actually liked, and I mentioned my trip to my boss. He said he’d been to the island, and of course I asked if he’d seen the ponies. He said yes, and said, “We brought a picnic and put all the food on a picnic table while we looked around, and when we came back to our table the ponies had eaten all our food. I cried. As a grown man, I cried.”

That’s literally what he said, and he wasn’t kidding. He was genuinely mad at those ponies for eating his picnic, which I find hilarious even though at the same time, yes, getting your picnic eaten by wild ponies is no fun. I’m sorry I laughed. Still, it’s really funny. Also, you’re not supposed to leave food out where the ponies can find it so it was his fault.

Anyway, I took Jasper to Assateague Island not knowing what to expect, except that if I left any food out, ponies would eat it. This was the first time I’d visited the ocean so far north and so late in the year, so I was surprised that the water was actually chilly. It was beautiful, though, and I enjoyed walking along the beach with Jasper. I thought he might have fun chasing waves, but he was quite an old dog at this point and was happy just to walk with me, although what he really wanted to do was go home to his regular routine. So we didn’t stay long, but we did see ponies! (Unfortunately I have lost all the pictures I took of the ponies and of Jasper, since this was before I got my first smartphone and all I had was a terrible little camera.)

About 75 ponies live in the northern part of Assateague, which is controlled by the state of Maryland, with about 150 more living in the southern part of the island, which is controlled by the state of Virginia. It gets confusing here because the Virginia part of Assateague is the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, but Chincoteague is actually a neighboring island that’s smaller than Assoteague but has a town, also named Chincoteague.

These islands are really very small. They’re barrier islands not far from the mainland coast, and while they change shape over time since they’re mostly just formed of sand, Assateague is only about 37 miles long, or 60 km, and only about 7 miles wide, or 11 km. Chincoteague is separated from Assateague by a small bay. The ponies in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge are taken care of by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department, and if you’ve read Misty of Chincoteague you probably already know what I’m about to tell you.

There are too many ponies on the island to thrive, no matter how small they are, because the island is so small. There’s just not enough food. The ponies eat whatever plants they can find in the salt marshes that make up large parts of the island, and they eat brush and seaweed and sometimes people’s picnics. Its small stature is mainly from its poor diet, since the foals don’t get enough nutrition when they’re growing.

In the early 19th century, the people of Chincoteague periodically rounded up some of the ponies and captured them, bringing them home to train and use as farm and riding animals. Hey, free horses! In 1924, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department took over the task of pony penning, making it into an annual event in July that attracts thousands of tourists.

The ponies are rounded up and made to swim across the bay, which sounds horrible but it’s a short swim, only five or maybe ten minutes long. Mounted riders swim alongside to help any foals who have trouble. When the horses arrive on Chincoteague, they’re given a good feed and a veterinarian checks them over and treats them if needed. Then the older foals are separated from the herd to auction off. The proceeds of the auction fund the fire department, the ponies are saved from starving to death by keeping their numbers down, and the ponies that aren’t sold are allowed to return home. To solve the same issue in the northern part of the island, members of the Maryland herd are given contraceptives that stop them from having very many babies.

More recently, starting in 1990, veterinarians have started treating the Virginia ponies twice a year to vaccinate them and treat any injuries or illnesses. This helps keep the herd healthy since so many of the foals born will eventually go on to live on the mainland around other horses, so it’s important that the ponies don’t carry diseases.

Another reason to keep the number of ponies low is because ponies aren’t the only animals that live on Assateague Island. Whitetail deer live on the island along with a whole lot of birds, some of which are endangered. Sika deer also live in marshy areas of the island, although it’s not native to North America. It was introduced to the island from Asia in 1923, although I have no idea why. The sika is mostly dark brown but it retains its white fawn spots into adulthood, and it’s a large, attractive animal.

The ponies have been on Assateague for several hundred years, and by the 1920s they were in genetically poor shape overall. To reduce the effects of inbreeding, Shetland and Welsh ponies were added to the herd, and later twenty mustangs were released on the island too. Arabian stallions were also allowed to mate with some of the Assateague mares who were captured and later returned to the island when they were in foal. This helped the Assateague pony survive with improved genetic health, but it also made it harder to determine where the ponies came from in the first place.

The big mystery about the Assateague ponies is how they got to the island. No one knows. Some historians think white colonists set their horses loose on the island in the 17th century so they wouldn’t have to pay livestock taxes, and this is very likely. Many colonists were from parts of the UK where letting your ponies roam free until you needed them was a normal practice. Other animals were allowed to roam free on the island at the time too, including cattle and sheep, but there’s another possibility.

A local legend claims that the ponies originated from horses brought by Spanish Conquistadors traveling to Peru. When one of the Spanish ships wrecked nearby, the horses swam to Assateague Island and survived there. There are plenty of shipwrecks along that part of the coast, including Spanish galleons. Maybe one of those ships had tough little horses aboard, and now we have tough little horses on Assateague Island. Just be glad they’re not kelpies, and hide your picnics.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!