Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:10 — 23.2MB)

It’s Nicholas’s episode this week, and Nicholas wants to learn more about hominins, the ancestors and cousins of modern humans!

Happy birthday to Autumn! I hope you have a great birthday!

Further listening:

Further reading:

Were Neanderthals the Earliest Cave Artists?

Neanderthals Built Mysterious Stone Circles

DNA reveals first look at enigmatic human relative

What does it mean to have Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA?

Hand and footprint art dates to mid-Ice Age

Risky food-finding strategy could be the key to human success

A stone circle in a cave was probably built by Neandertals:

A deer bone with carving on it probably made by Neandertals:

Some cave paintings probably made by Neandertals:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast! I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is Nicholas’s episode! Nicholas wanted an updated episode about hominins, our ancient ancestors or species closely related to modern humans. The last time we talked about hominins was way back in episodes 25 and 26, so it’s definitely time to revisit the topic.

But first, a big birthday shout-out to Autumn! Happy birthday, Autumn, and I hope you have the best birthday so far!

If you haven’t listened to episode 25 in a while, or ever, I recommend you go back and give it a listen if you want background information about how humans evolved and our closest extinct relatives, Neandertals and Denisovans. I’ve transcribed that episode finally, so you can read the episode instead of listen to it if you prefer. There’s a link in the show notes.

Results of a study published in January 2022 in the journal Nature has finally dated the oldest known Homo sapiens remains found so far. The remains were found in Ethiopia in the 1960s but the volcanic ash found over them was too fine-grained to date with any certainty. Finally, though, the eruption has been determined to come from a volcano almost 250 miles, or 400 km, away from the remains. The Shala eruption was enormous and took place 230,000 years ago, so since the remains were found below the ash, the person had to have lived at least 230,000 years ago too.

We’re still learning more about humans and our closest relations because new hominin fossils are being found and studied all the time. But the fossil record doesn’t tell the whole story. Only a small percentage of bones ever fossilize, and of those, only a tiny fraction are ever found by scientists. But technological advances in genetic testing means that scientists can now extract DNA from the soil. All animals shed fragments of DNA all the time, from skin cells and hairs to poop. A study published in 2021 was able to isolate Neandertal DNA from sediments in three different caves. The DNA matched the known fossils found at the sites and gave more information besides. Instead of being restricted to a single individual whose bones were found and tested, genetic testing of sediments gives genetic information about lots of individuals. In the case of a cave in northern Spain, where lots of stone tools have been found but only a single Neandertal toe bone, it turns out that two different populations of Neandertal had lived in the cave over 100,000 years ago.

In episode 25, I mentioned that Neandertals didn’t seem to make things the way humans do, especially art. Some researchers even suggest that they couldn’t think symbolically the way humans do. But in the five years or so since that episode, we’ve learned a lot more about Neandertals–and they seem to have been pretty artistic after all.

The main problem is that historically, whenever scientists found rock art or carvings from prehistoric times, they assumed humans made it. We might be a little biased. Some art originally thought to be made by humans is now thought to have been made by Neandertals. Most of it is found in caves. Remains of animals are often found in caves because the cave protects them from weather and other factors that can destroy them, and the same is true for archaeological remains.

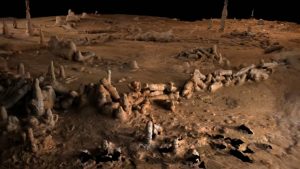

In 1990, a team of cavers dug into a narrow collapsed cave entrance and entered Bruniquel Cave in southwest France that no human—in fact, no animal from the surface world—had entered since the entrance collapsed during the Pleistocene. That was at least 24,000 years ago and probably much, much longer.

The cavers found the bones of long-extinct Pleistocene megafauna near the entrance, including cave bears. But it wasn’t until they reached a chamber deeper inside the cave that they made a stupendous discovery.

The chamber held a big stone circle made of broken-off pieces of stalactite and stalagmite and other rock formations. The pieces are all about the same size and are arranged in a circle almost 22 feet across, or 6.7 meters. There’s a smaller semicircle in the chamber too and heaps of more stone pieces. Some of the stones show signs of fires being lit on top of them, and a piece of burnt bone from a bear or other large animal was found near the semicircle.

The cavers alerted local scientists, who came to investigate. At first they thought the structures had been built by early humans. They took samples for testing, and that’s when they got another shock. The burnt bone, the fire residue, and the minerals growing over both revealed an age long before 40,000 years ago, which is when humans first moved into the area. The stone circle was built 176,000 years ago. And the only hominin known to live in Europe that long ago was the Neandertal.

We don’t know what Neandertals used the stone circles for. It might have been a living space, but it might have been religious in nature instead. Either way, it shows that even that long ago, Neandertals had full control over fire to the point that they could make light sources to find their way deep into a cave, and had the curiosity to want to explore deeper into a cave than they really needed to go for shelter.

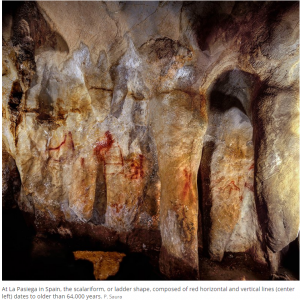

There are lots of other examples of Neandertal art and intelligence found in Europe. For instance, paintings in a cave in Spain have been dated to at least 65,000 years ago. Remember, humans didn’t reach Europe until about 40,000 years ago. The paintings are made of red mineral pigment, including elaborate rows of dots, geometric figures, and occasionally animal figures and hand stencils. Other caves in the area also have similar rock art dating to Neandertal times.

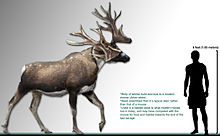

In a cave in Germany, researchers found a piece of deer bone dated to 51,000 years ago that has a carved pattern in it. The carving is too elaborate to be simple butcher marks, but again, humans hadn’t yet moved into Europe 51,000 years ago. The bone actually comes from the leg of a giant deer, once called the Irish elk, that we talked about way back in episode 4. In another cave in Gibraltar, cross-hatched patterns carved in the rock have been dated to more than 39,000 years ago and are associated with artifacts made by Neandertals.

Archaeologists have also found a lot of toe bones from eagles that are etched with cut marks, found in various sites throughout southern Europe. They think Neanderthals in this area wore eagle talons as jewelry, and most likely feathers too.

There’s still controversy when it comes to Neandertals and art. Some researchers think Neandertals only used art after they saw humans making it. Some think the art isn’t art at all but something else, like accidental marks left by other activities. Some think the dating methods used to determine the age of paintings is flawed.

Another criticism is that we don’t actually know that Neandertals made the art; we just know it probably couldn’t have been humans. But there were other human relations living at the same time.

One of those is the Denisovan people, named for Denisova Cave in the mountains of Siberia. Hominins didn’t ordinarily live in caves, but sometimes they did. This seems to be the case in Denisova Cave, where evidence of human habitation, Neandertal habitation, and habitation by another hominin goes back some 180,000 years.

Researchers knew about humans and Neandertals living in the cave, but it wasn’t until 2010 that they realized a third hominin had lived there at various times. The Denisovan people were closely related to both Neandertals and humans and probably looked a lot like Neandertals, with a robust build and big teeth. We still don’t know a whole lot about them, but they lived in parts of what is now Asia and possibly nearby areas, and they might not have gone extinct until about the same time that Neandertals did, around 30,000 years ago.

We talked about the Denisovans in episode 25, but since then new remains have been discovered in other caves. The most exciting is a partial jawbone with two teeth that was found by a Buddhist monk in a cave on the Tibetan plateau in 1980, but not studied until much later. It was identified as a Denisovan mandible in 2019 and dated to 160,000 years ago.

Genetic testing of Denisovan remains indicate that Denisovans and Neandertals were probably more closely related to each other than to humans, although all three species were very closely related. Since there are so few Denisovan remains known, we don’t have a very good idea yet of where they lived and what they were like. We do have genetic markers that indicate the Denisovans had dark skin, brown hair, and brown eyes, while Neandertals, like humans, were more varied in skin, hair, and eye color.

Geneticists have identified traces of Denisovan DNA in some populations of modern humans, including in Asia, New Guinea and surrounding areas, and Australia. This is a reminder that even though some human populations contain DNA traces from our extinct cousins, all humans are thoroughly human. Those bits and bobs of ancient DNA are too small to be significant.

We do have what seems to be art made by Denisovans, although not everyone agrees that it was intended to be art in the way we think of it. It was found in the Tibetan Plateau and we now know that Denisovans lived in the area, although when it was found in 1998 we didn’t even know Denisovans existed. The art was found near hot springs and dated to as much as 226 thousand years ago, although it might have been closer to 169 thousand years ago. Either way, it was well before modern humans are known to have lived in the area. The art consists of footprints and hand prints pressed into the mud, probably by two individuals. The artists pressed their hands, feet, fingers, thumbs, and in one case a forearm into the mud around the hot springs, making patterns. But the thing is, these prints are small even by human standards. Researchers are pretty sure they were made by children, so while it’s certainly possible the children were creating art, they also might just have been messing around having fun in the mud. But the fact that they were making patterns points to an artistic intelligence. Puppies play and may stomp their feet in mud, but they don’t get interested in making patterns of their footprints in the mud. Human children do.

There’s still at least one other hominin that lived at the same time as Neandertals, Denisovans, and humans. We only know about that hominin because researchers have identified their DNA in genetic studies of Denisovans, which means they interbred. It’s a ghost lineage that no one guessed existed until genetic studies of Denisovans and Neandertals were completed in the early 2010s. It might turn out to be a known hominin such as Homo erectus but it might be a completely unknown species.

Of course we have lots of information about art made by ancient humans. It’s been found throughout the world. No one’s in any doubt that our prehistoric ancestors were just as intelligent and artistic as humans who live today, they just didn’t have the technology we have. I can go to an art supply store and buy paints in any color I want, assuming I don’t just want to paint digitally, but in prehistoric times human artists had to make their own paints from the things they found in nature. This included minerals like red ochre and yellow ochre, umber, calcite, hematite, iron oxide, and lots more. They used burnt bones and charcoal for black. These minerals are all still used to make modern oil paints (used in art, not for painting a room or a house), with names like bone black and lime white.

Many minerals have to be processed before they can be used as pigments. Ochre, for instance, has to be heated to 850 degrees Fahrenheit, or 750 Celsius, to change into the rich red-orange that ancient artists especially liked. After processing, the pigments were ground into powder, then mixed with various substances to make a paste. These substances included fat, blood, spit, plant oils, tree sap, water, bone marrow, and even urine.

Ancient artists used their fingers to paint, but they also used twigs, brushes made from animal hair, and mats of lichen. Sometimes they blew pigment onto a surface with their breath, first putting the paint into a hollow tube and then blowing into the tube to spray paint. This is the same way airbrushes work, but no one gets light-headed using an airbrush because a machine is doing the blowing air part. If the artist was working in a cave, they also needed a light source, specifically fire, so they could see what they were doing. It’s all a lot of work.

Aside from all the details involved in getting ready to paint, making art takes one other really important commodity: time. Great apes spend most of their time finding food and eating it. How did ancient humans find time to paint without starving?

A study released in early 2022 points out that hominins developed a much different strategy for getting food than our more distant ape relations. Apes mostly eat plant material, especially fruit, which is nutritious but takes a lot to fulfill the calorie needs of an adult. Early hominins were hunter-gatherers, meaning they both hunted animals and gathered plant material to eat. But because hominins are intensely social and share food, we could take risks that other animals can’t. A group of ancient humans could go out to hunt something big knowing that even if they failed, when they got home they wouldn’t go hungry. Other people would have been gathering food all day and would share. But if the hunters got lucky and brought home a big animal like a deer, everyone had lots and lots of high calorie food to go around. With food available to everyone, people could take time to do things that didn’t directly relate to finding food, like art.

Not only that, another study published in 2019 discovered that some early hominins had already figured out how to preserve food several hundred thousand years ago. The food in question was bone marrow, which is found inside bones and which is extremely nutritious. Researchers have always assumed hominins would crack the bones of animals they killed to get at the marrow as soon as possible. But deer bones found in a cave near Tel Aviv, Israel were stored unbroken, with the skin still on. Researchers determined that the bones were kept in the cave for up to nine weeks before being broken open. By keeping the skin on the bones and storing them in the cave, where the temperature was cool, the marrow stayed fresh. That way there was always something nutritious to eat in the cupboard, so to speak.

Art doesn’t have to be paintings or carvings. Ancient humans were probably using plant fibers to make things more than 34,000 years ago. The fibers are from wild flax plants, and flax is still used today to make linen fabric. Fragments of flax fibers were found in a cave in the Republic of Georgia (which is a country, not the American state of Georgia) where other human artifacts were found. Since flax isn’t edible, at least not by humans, researchers think the fiber might have been used to make thread, rope, baskets, and possibly even cloth. You know, clothing.

One thing to remember is that humans, Neandertals, and Denisovans were so closely related that they could and did interbreed and produce fertile offspring. That means not only were our extinct cousins very similar to us physically, they were probably pretty similar to us mentally too. It would be more surprising if they didn’t produce art that represented symbolic thinking, since it’s such an important part of the human experience.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!