Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:49 — 22.5MB)

Thanks to Anbo for suggesting Australopithecus! We’ll also learn about Gigantopithecus and Bigfoot!

Further reading:

Ancient human relative, Australopithecus sediba, ‘walked like a human, but climbed like an ape’

Human shoulders and elbows first evolved as brakes for climbing apes

You Won’t Believe What Porcupines Eat

Past tropical forest changes drove megafauna and hominin extinctions

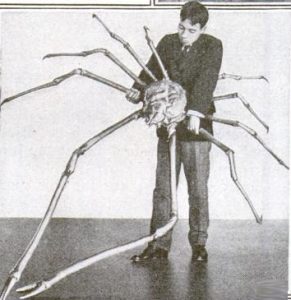

An Australopithecus skeleton [photo by Emőke Dénes – kindly granted by the author, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78612761]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s officially monster month, also known as October, so let’s jump right in with a topic suggested by Anbo! Anbo wanted to learn about Australopithecus, and while we’re at it we’re going to talk about Gigantopithecus and Bigfoot. On our spookiness rating scale of one to five bats, where one bat means it’s not a very spooky episode and five bats means it’s really spooky, this one is going to fall at about two bats, and only because we talk a little bit about the Yeti and Bigfoot at the end.

In 1924 in South Africa, the partial skull of a young primate was discovered. Primates include monkeys and apes along with humans, our very own family tree. This particular fossil was over a million years old and had features that suggested it was an early human ancestor, or otherwise very closely related to humans.

The fossil was named Australopithecus, which means “southern ape.” Since 1924 we’ve discovered more remains, enough that currently, seven species of Australopithecus are recognized. The oldest dates to a bit over 4 million years old and was discovered in eastern Africa.

Australopithecus was probably pretty short compared to most modern humans, although they were probably about the size of modern chimpanzees. A big male might have stood about 4 ½ feet tall, or 1.5 meters. They were bipedal, meaning they would have stood and walked upright all the time. That’s the biggest hint that they were closely related to humans. Other great apes can walk upright if they want, but only humans and our closest ancestors are fully bipedal.

In 2008 a palaeoanthropologist named Lee Rogers Berger took his nine-year-old son Matthew to Malapa Cave in South Africa. Dr. Berger was leading an excavation of the cave and Matthew wanted to see it. While he was there, Matthew noticed something that even his father had overlooked. It turned out to be a collarbone belonging to an Australopithecus boy who lived almost 2 million years ago. Later, Dr Berger’s team uncovered more of the skeleton and determined that the remains belonged to a new species of Australopithecus, which they named Australopithecus sediba. More remains of this species were discovered later, including a beautifully preserved lower back. That discovery was important because it allowed scientists to determine that this species of Australopithecus had already evolved the inward curve in the lower back that humans still have, which helps us walk on two legs more easily. That was a surprise, since A. sediba also still shows features that indicate they could still climb trees like a great ape.

It’s possible that Australopithecus, along with other species of early humans, climbed trees at night to stay safe from predators. In the morning, they climbed down to spend the day mostly on the ground. One study published only a few weeks ago as this episode goes live suggests that the flexible shoulders and elbows that humans share with our great ape cousins originally evolved to help apes climb down from trees safely. Monkeys don’t share our flexible shoulder and elbow joints because they’re much lighter weight than a human or ape, and don’t need as much flexibility to keep from falling while climbing down. Apes and hominins like humans can raise our arms straight up over our heads, and we can straighten our arms out completely flat. Australopithecus could do the same. The study suggests that when another human ancestor, Homo erectus, figured out how to use fire, they stopped needing to climb trees so often. They evolved broader shoulders that allowed them to throw spears and other weapons much more accurately.

Australopithecus probably mostly ate fruit and other plant materials like vegetables and nuts, along with small animals that they could catch fairly easily. This is similar to the diet of many great apes today. The big controversy, though, is whether Australopithecus made and used tools. Their hands would have been more like the hands of a bonobo or chimpanzee, which have a lot of dexterity, but not the really high-level dexterity of modern humans and our closest ancestors. Stone tools have been found in the same areas where Australopithecus fossils have been found, but we don’t have any definitive proof that they made or used the tools. There were other early hominins living in the area who might have made the tools instead.

We also don’t really know what Australopithecus looked like. Some scientists think they had a lot of body hair that would have made them look more like apes than early humans, while some scientists think they had already started losing a lot of body hair and would have looked more human-like as a result.

There’s no question these days that Australopithecus was an early human ancestor. We don’t have very many remains, but we do have several skulls and some nearly complete skeletons, which tells us a lot about how our distant ancestor lived. But we know a lot less about a fossil ape that lived as recently as 350,000 years ago, and it’s become confused with modern stories of Bigfoot.

Gigantopithecus first appears in the fossil record about 2 million years ago. It lived in what is now southern China, although it was probably also present in other parts of Asia. It was first discovered in 1935 when an anthropologist identified two teeth as belonging to an unknown species of ape, and since then scientists have found over a thousand teeth and four jawbones, more properly called mandibles.

The problem is that we don’t have any other Gigantopithecus bones. We don’t have a skull or any parts of the body. All we have are a few mandibles and lots and lots of teeth. The reason we have so many teeth is because Gigantopithecus had massive molars, the biggest of any known species of ape, with a protective layer of enamel that was as much as 6 mm thick. Some of the teeth were almost an inch across, or 22 mm. A lot of the remaining bones were probably eaten by porcupines, and in fact the mandibles discovered show evidence of being gnawed on. This sounds bizarre, but porcupines are well-known to eat old bones along with the shed antlers of deer, which supplies them with important nutrients. The teeth were too hard for the porcupines to eat.

We know that Gigantopithecus was a big ape just from the size of its mandible, but without any other bones we can only guess at how big it really was. It was potentially much bigger and taller than even the biggest gorilla, but maybe it had a great big jaw but short legs and it just sat around and ate plants all the time. We just don’t know.

What we do know is that its massive jaw and teeth were adapted for eating fibrous plant material, not meat. The thick enamel would help protect the teeth from grit and dirt, which suggested it ate tubers and roots that would have had a lot of dirt on them, although its diet was probably more varied. Scientists have even discovered traces of seeds from fruits belonging to the fig family stuck in some of the fossilized teeth, and evidence of tooth cavities that would have resulted from eating a lot of fruit long before toothpaste was invented.

Many scientists thought at first that Gigantopithecus was a human ancestor, but one that grew to gigantic size. It was even thought to be a close relation to Australopithecus. Other scientists argued that Gigantopithecus was more closely related to modern great apes like the orangutan. The debate on where Gigantopithecus should be classified in the ape and human family tree happened to overlap with another debate about a giant ape-like creature, the Yeti of Asia and the Bigfoot of North America.

We talked about the Yeti way back in episode 35, our very first monster month episode in 2017. Expeditions by European explorers to summit Mount Everest, which is on the border between China and Nepal, started in 1921. That first expedition found tracks in the snow resembling a bare human foot at an elevation of 20,000 feet, or 6,100 meters. They realized the tracks were probably made by wolves, with the front and rear tracks overlapping, which only looked human-like after the snow melted enough to obscure the paw pads. Expedition leader Charles Howard-Bury wrote in a London Times article that the expedition’s Sherpa guides claimed the tracks were made by a wild hairy man, but he also made it clear that this was just a superstition. But journalists loved the idea of a mysterious wild man living on Mount Everest. One journalist in particular, Henry Newman, interviewed the guides and specifically asked them about the creature. He wrote a sensational account of the wild man, but he mistranslated their term for it as the abominable snowman.

The word Yeti comes from a Sherpa term yeh-teh, meaning “animal of rocky places,” although it may be related to the term meh-teh, which means man-bear. But the peoples who live in and around the Himalayas belong to different cultures and speak a lot of different languages. There are lots of stories about the hairy wild man of the mountains, and lots of different words to describe the creature of those stories. And the idea of the Yeti that has become popular in Europe and North America doesn’t match up with the local stories. Locals describe the Yeti as brown, black, or even reddish in color, not white, and it doesn’t always have human-like characteristics. Sometimes it’s described as bear-like, panther-like, or just a general monster.

The abominable snowman, or Yeti, became popular in newspaper articles after the 1921 Mount Everest expedition, and it continued to be a topic of interest as expeditions kept attempting to summit the mountain. It wasn’t until May 26, 1953 that the first humans reached the tippy-top of Mount Everest, the New Zealand explorer Edmund Hillary and the Nepali Sherpa climber Tenzing Norgay. Many other successful expeditions followed, including some that were mounted specifically to search for the Yeti.

In the meantime, across the planet in North America, a Canadian schoolteacher and government agent named John W. Burns was collecting reports of hairy wild men and giants from the native peoples in British Columbia. He’s the one who coined the term Sasquatch in 1929. In the 1930s, a man in Washington state in the U.S, which is close to British Columbia, Canada, carved some giant feet out of wood and made tracks with them in a national forest to scare people, leading to a whole spate of big human-like tracks being faked in California and other places. But it wasn’t until 1982 that the hoaxes started to be revealed as the perpetrators got old and decided to clear up the mystery.

But in the 1920s and later, the popularity of the abominable snowman in popular media, giant gorillas like King Kong in the movies, the Yeti expeditions in the Himalayas, the mysterious giant footprints on the west coast of North America, and John Burns’s articles about the Sasquatch all combined to make Bigfoot, a catchall term for any giant human-like monster, a modern legend. People who believed that Bigfoot was a real creature started looking for evidence of its existence beyond footprints and reports of sightings. In 1960, a zoologist writing about a photograph of supposed Yeti tracks taken in 1951 suggested that the Yeti might be related to Gigantopithecus.

On the surface this actually makes sense. The Yeti, AKA the abominable snowman, is reported in the Himalayan Mountains of Asia. The mountain range started forming 40 to 50 million years ago when the Indian tectonic plate crashed into the Eurasian plate very slowly, pushing its way under the Eurasian plate and scrunching the land up into massively huge mountains. It’s still moving, by the way, and the Himalayas get about 5 mm taller every year. The eastern section of the Himalayas isn’t that far from where Gigantopithecus remains have been found in China, and we also know that at many times in the earth’s recent past, eastern Asia and western North America were connected by the land bridge Beringia. Humans and many animals crossed Beringia to reach North America, so why not Gigantopithecus or its descendants? That would explain why Bigfoot is so big, since in 1957 one scientist estimated that Gigantopithecus might have stood up to 12 feet tall, or 3.7 meters.

Some people still think Gigantopithecus was a cousin of Australopithecus, that it walked upright but was huge, and that its descendants are still around today, hiding in remote areas and only glimpsed occasionally. But people who believe such an idea are stuck in the past, because in the last 60 years we’ve learned a whole lot more about Gigantopithecus.

These days, more sophisticated study of Gigantopithecus fossils have allowed scientists to classify it as a great ape ancestor, not an early human. Gigantopithecus was probably most closely related to modern orangutans, in fact, and may have shared a lot of traits with orangutans. It probably could walk upright if it wanted to, but it wasn’t fully bipedal the way humans and human ancestors are. One theory prevalent in 2017 when we talked about the Yeti before was that Gigantopithecus mostly ate bamboo and might have gone extinct when the giant panda started competing with its food sources. This theory has already fallen out of favor, though, and we know that Gigantopithecus was eating a much more varied diet than just bamboo.

We also know that Gigantopithecus lived in tropical broadleaf forests common throughout southern Asia at the time. About a million years ago, though, many of these forests became grasslands. Gigantopithecus probably went extinct as a direct result of its forest home vanishing. It just couldn’t find enough food and shelter on open grasslands, and even though it held on for hundreds of thousands of years, by about 350,000 years ago it had gone extinct. Around 100,000 years ago the forests started reclaiming much of these grasslands, but by then it was too late for Gigantopithecus. Meanwhile, the oldest evidence we have of the land bridge Beringia joining Asia and North America was 70,000 years ago.

There is no evidence that any Gigantopithecus descendant survived to populate the Himalayas or migrated into North America. For that matter, there’s no evidence that Bigfoot actually exists. If a live or dead Bigfoot is discovered and studied by scientists, that would definitely change a lot of things, and would be really, really exciting. But even if that happened, I’m pretty sure we’d find that Bigfoot wasn’t related to Gigantopithecus. Whether it would be related to Australopithecus and us humans is another thing, and that would be pretty awesome. But first, we have to find evidence that isn’t just some footprints in the mud or snow.

Some Bigfoot enthusiasts suggest that the reason we haven’t found any Bigfoot remains is the same reason why we don’t have Gigantopithecus bones, because porcupines eat them. But while porcupines do eat old dry bones they find, they don’t eat fresh bones and they don’t eat all the bones they find. For any bone to fossilize is rare, so the more bones that are around, the more likely that one or more of them will end up preserved as fossils. Bones of modern animals are much easier to find, porcupines or no, but we don’t have any Bigfoot bones. We don’t even have any Bigfoot teeth, which porcupines don’t eat.

Porcupines can be blamed for a lot of things, like chewing on people’s cars and houses, but you can’t blame them for eating up all the evidence for Bigfoot.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!