Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 19:58 — 22.9MB)

Thanks to Joel for suggesting this week’s topic!

Happy birthday to Fern this week!

Further reading:

Small, rare crayfish thought extinct is rediscovered in cave in Huntsville city limits

Hundreds of three-eyed ‘dinosaur shrimp’ emerge after Arizona monsoon

An invertebrate mystery track in South Africa

The case of the mysterious holes in the sea floor

The Shelton Cave crayfish, rediscovered:

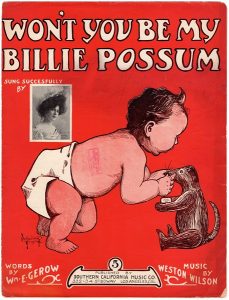

The three-eyed “tadpole shrimp” or “dinosaur shrimp,” triops [photo from article linked above]:

A leech track in South Africa [photo from article linked above]:

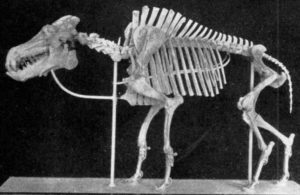

A track, or at least a series of holes, discovered in the deep seafloor [photos from article linked above]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Thanks to Joel who suggested we do an episode about mystery invertebrates! It took me a while, but I think you’re really going to like this episode. Some of the mysteries are solved and some are not, but they’re all fun.

Before we get to the mystery animals, though, we have a birthday shout-out! A great big happy birthday to Fern! I hope you have your favorite type of birthday cake or other treat and get to enjoy it with your loved ones.

Our first mystery starts in a cave near Huntsville, Alabama in the southern United States, which is in North America. Shelta Cave is a relatively small cave system, only about 2,500 feet long, or 760 meters. That’s about half a mile. It’s a nature preserve now but in the early 1900s it was used as an underground dance hall with a bar and everything.

Biologist John Cooper studied the cave’s aquatic ecosystem in the 1960s when he was doing his dissertation work. His wife Martha helped him since they were both active cavers. At the time, the cave ecosystem was incredibly diverse, including three species of crayfish. One was called the Shelta Cave crayfish, which was only a few inches long, or about 5 cm, mostly translucent or white since it didn’t have any pigment in its body, and with long, thin pincers.

It was rarer than the cave’s other two crayfish species, and unlike them it had only ever been found in Shelta Cave. From 1963 to 1975, only 115 individuals had been confirmed in repeated studies of the cave’s ecosystem.

Then, in the 1970s, several things happened that caused a serious decline in the diversity of life in the cave.

The first was development of the land around the cave into subdivisions, which meant that more pesticides were used on lawns and flower beds, which made its way into the groundwater that entered the cave. It also meant more people discovering the cave and going in to explore, which was disturbing a population of gray bats who also lived in the cave. To help the bats and keep people out, the park service put a gate over the entrance, but the initial gate’s design wasn’t a very good one. It kept people out but it also made it harder for the bats to go in and out, and eventually the bats gave up and moved out of the cave completely. This really impacted the cave’s ecosystem, since bats bring a lot of nutrients into a cave with their droppings and the occasional bat who dies and falls to the cave floor.

The gate has since been replaced with a much more bat-friendly one, but studies afterwards showed that a lot of the animals found in the cave had become rare. The Shelta Cave crayfish had disappeared completely. One was spotted in 1988 but after that, nothing, and the biologists studying the cave worried that it had gone extinct.

Then, in 2019, a team of scientists and students surveying life in the cave spotted a little white crayfish with long, thin pincers in the water. The team leader dived down and scooped it up with his net to examine more closely. The crayfish turned out to be a female Shelta Cave crayfish with eggs, which made everyone excited, and after taking a tiny tissue sample for DNA testing, and lots of photographs, they released her back into the water. The following year they found a second Shelta Cave crayfish.

The Shelta Cave crayfish is so little known that we don’t even know what it eats or how it survives in the same environment with two larger crayfish species. Biologist Dr. Matthew Niemiller is continuing Dr. Cooper’s initial studies of the cave and will hopefully be able to learn more about the crayfish and its environment.

Next let’s travel from a cool, damp, flooded cave in Alabama to northern Arizona. Arizona is in the western United States and this particular part of the state has desert-like conditions most of the year. Almost a thousand years ago, people built what is now called Wupatki Pueblo, a 100-room building with a ballcourt out front and a big community room. It was basically a really nice apartment building. Wupatki means “tall house” in the Hopi language, and while the pueblo people who built it are long gone, Wupatki is still an important place for the Hopi and other Native American tribes in the area. It’s also a national monument that has been studied and restored by archaeologists and is open to the public.

In late July 2021, torrential rain fell over the area, so much rain that it pooled into a shallow temporary lake around Wupatki, including flooding the ballcourt. The ballcourt is 105 feet across, or 32 meters, and surrounded by a low wall. One day while the ballcourt was still flooded, a tourist came up to the lead ranger, Lauren Carter. The visitor said there were tadpoles in the ballcourt.

There are toads in the area that live in burrows and only come out during the wet season when there’s rain, and Carter thought the tadpoles might be from the toads. She went to investigate, saw what looked like tadpoles swimming around, and scooped one up in her hands to take a closer look. But the tadpoles were definitely not larval toads. In fact, they kind of looked like teensy horseshoe crabs, with a rounded shield over the front of the body and a segmented abdomen and tail sticking out from behind, with two long, thin spines at the very end that are called caudal extensions. It had two pairs of antennae and lots of small legs underneath, some adapted for swimming. The largest of the creatures were about two inches long, or 5 cm.

What on earth were they, and where did they come from? This area is basically a desert. Carter stared at the weird little things and remembered hearing about something similar when she worked at the Petrified Forest National Park, also in Arizona. She looked the animal up and discovered what it was.

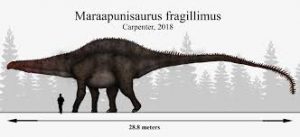

It’s called Triops and is in the order Notostraca. Notostracans are small crustaceans shaped sort of like tadpoles, which is why it’s sometimes called the tadpole shrimp, but it’s not a shrimp. It has two eyes on the top of its head visible through its flattened, smooth carapace. Species in the genus Triops also have a so-called third eye between the two ordinary eyes, although it’s a very simple eye that probably only detects light and dark. Many crustaceans have these third eyes in their larval forms but very few retain them into adulthood.

Notostracans have been around for about 365 million years, and haven’t changed much in the last 250 million years. It’s an omnivore that mostly lives on the bottom of freshwater pools and shallow lakes, often temporary ones like the flooded ballcourt, although some species live in brackish water and saline pools, or permanent waterways like peat bogs.

Triops eggs are able to tolerate high temperatures and dry conditions, with the eggs remaining viable for years or even decades in the sediment of dried-up ponds. When enough water collects, the eggs hatch and within 24 hours are miniature versions of the adult Triops. They grow up quickly, lay lots of eggs, and die within a few months or when the water dries up again.

Triops eggs are even sold as aquarium pets, since they’re so unusual looking and are easy to care for. They basically eat anything. They especially like mosquito larvae, so if you see some in your local pond or other waterway, give them a tiny high-five.

In 1996, some workers near Indianapolis, Indiana were servicing a tank full of chemical byproducts from making plastic auto parts when they noticed movement in the toxic goo. They investigated and saw several squid-like creatures swimming around. They were red-brown and about 8 inches long, or 20 cm, including their arms or tentacles, but were only about an inch wide, or 2.5 cm.

The workers managed to capture one and put it in a jar, which they stuck in the break room refrigerator. By the time someone in management arranged to have it examined by a scientist, the jar had been thrown out. If you’ve ever tried to keep food in a break room fridge, you’ll know that there’s always someone who will throw out everything in the fridge that isn’t theirs, no matter whether it’s labeled or brand new or not. I have had my day’s lunch thrown out that had only been in the fridge a few hours. Anyway, when the tank was cleaned out the following year, no one found any creatures in it at all.

This sounds really interesting, but there’s precious little information to go on. The story appeared in a few newspapers but we have no names of the people who reportedly saw the creatures, no follow-up information. It has all the hallmarks of a hoax or urban legend. The creatures’ size also seems quite large for extremophiles in a small, closed environment. What would they find to eat to get so big?

Next let’s talk about some mysterious tracks made by invertebrates, as far as we know. We’ll start with a track on land that was a mystery at first, but was solved. A man in the Kruger National Park in South Africa named Rudi Hulshof came across a weird track in the sandy dirt that he didn’t recognize. It was maybe 10 mm wide and kind of looked like a series of connected rectangles, as though a tiny person was moving a tiny cardboard box by rolling it over and over, but there weren’t any footprints, just the body track.

Curious, Hulshof followed the track to find what had made it, and finally discovered the culprit. It was a leech! Most leeches live in water, whether it’s the ocean, a pond or swamp, a river, or just flooded ground. Most species are parasitic worms that attach to other animals with suckers, then pierce the animal’s skin and suck its blood. The leech stays on the animal until it’s full, then drops off. Some leeches are terrestrial, but it appears that this one was a freshwater leech that had attached to an animal passing through the water, then dropped off onto land. It had crawled as far as it could trying to find a better environment, but when Hulshof found it it was dead, so it had not had a good day.

The leech moves on land by stretching the front of its body forward, then dragging its tail end up in a bunch kind of like a worm (it is a kind of worm), so that’s why its track was so unusual-looking. It’s a good thing Hulshof found the leech before something ate it, or else he’d probably still be wondering what had made that track.

We have photographs of other tracks that are still mysterious. You may have heard about one that’s been in the news lately. This one was found by a deep-sea rover in July 2022, more than a mile and a half deep, or 2500 meters, in the north Atlantic Ocean.

The track may or may not actually be a track, although it looks like one at first glance. It consists of a line of little holes in the seafloor, one after the other, although they’re not all the same distance apart. The rover saw them on two separate dives in different locations, so it wasn’t just one track, but although the scientists operating the rover remotely tried to look into the holes, they couldn’t get a good enough view. It does look like there’s sediment piled up next to the holes, so researchers think something might actually be digging the holes, either digging down from the surface to find food hidden in the sediment, or digging up from inside the sediment to find food in the water. The rover did manage to get a sample of sediment from next to one of the holes and a water sample from just above it, and eventually those samples will be tested for possible environmental DNA that might help solve the mystery.

This wasn’t the first time these holes have been seen in the area, though. An expedition in 2004 saw them and hypothesized that the holes are made by an invertebrate with a feeding appendage of some kind that it uses to dig for food. Not only that, we have similar-looking fossil holes in rocks formed from deep marine sediments millions of years ago.

Other deep-sea tracks have a known cause, and humans are responsible. In the 1970s and 1980s, ships with deep-sea dredging equipment traveled through parts of the Pacific Ocean, testing the ocean floor to see whether the minerals in and beneath the sediment were valuable for mining. A few years ago scientists revisited the same areas to see how the ecosystems impacted by test mining had responded.

The answer is, not well. Even after 40 years or so since the deep-sea mining equipment sampled the sea floor, the marks remain. The deep sea is a fragile ecosystem to start with, and any disturbance takes a long, long time to recover—possibly thousands of years. So while the holes discovered in 2022 were almost certainly made by an animal or animals, they might be quite old.

Let’s finish with a mystery animal we’ve talked about before, but a really long time ago—way back in episode 6. It’s definitely time to revisit it.

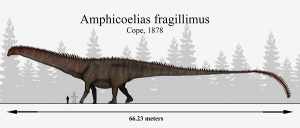

In 1883 when he was 18 years old, a Vietnamese man named Tran Van Con had seen the body of an enormous creature washed up on shore at Hongay in Vietnam. Van Con said it was probably 60 feet long, or 18 meters, but less than three wide wide, or 90 cm. It had dark brown plates on its back with long spines sticking out from them to either side, and the segment at its tail end had two more spines pointing straight back. It didn’t have a head, which had presumably already rotted off, or something bit it off before the animal washed ashore. It had been dead for a long time considering the smell. In fact, it smelled so terrible that locals finally towed it out to sea to get rid of it. It sank and that was the last anyone ever saw of it. The locals referred to it as a con rit, which means “millipede,” since the armor plates made it look like the segmented body of an immense millipede.

Lots of people have made suggestions as to what the con rit could be, but nothing really fits. It was the length of a whale, but it doesn’t sound like any kind of whale known. The armored plates supposedly rang like metal when hit with a stick. Even if this was an exaggeration, it probably meant the armor plates were really hard, not just the skin of a dead whale that had hardened in the sun. It also implies that the plates had empty space under them, allowing them to echo when hit. Zoologist Dr. Karl Shuker suggests that the plates might have been the exoskeleton of a crustacean of some kind, which makes a lot more sense than a whale, but the sheer size of the carcass is far larger than any crustacean, or even any arthropod, ever known.

There’s also some doubt that the story is accurate. It might even be a hoax. We only know about the con rit at all because the director of Indochina’s Oceanographic and Fisheries service, Dr. A. Krempf, talked to Tran Van Con about it in 1921. That was 38 years after Van Con said he saw the creature, so he might have misremembered details. Not only that, Krempf translated the story from Vietnamese, and there’s no way of knowing how accurate his translation was.

The con rit is also a monster from Vietnamese folktales, a sort of sea serpent that had lots of feet. It was supposed to attack fishing boats to eat the sailors, until a king caught it and chopped it up into pieces. A local mountain was supposedly formed from its head, and the other pieces of its body turned into the unusual stones found on a nearby island.

There’s always the possibility that Tran Van Con actually told Krempf this folktale, but that Krempf misunderstood and thought he was telling him something he actually witnessed. Then again, there are eight reports from ships in the area between 1893 and 1915 of creatures that might have been a con rit. One account from 1899 was a sighting of a creature estimated as being 135 feet long, or 41 meters, which was rowing itself along at the surface by means of multiple fins along its sides.

Whatever the con rit was, there haven’t been any sightings since 1915. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a population of incredibly long invertebrates living in the deep ocean in southeast Asia. If it does exist, maybe one day a deep-sea rover will spot one. Maybe it dug those little holes, who knows?

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!