Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:09 — 10.3MB)

As we get closer and closer to Halloween, the monsters get scarier and scarier! Okay, spiders are not technically monsters, but some people think they are. Don’t worry, I keep descriptions to a minimum so arachnophobes should be okay! This week we learn about some spider friends and some spider mysteries.

I stole the above cartoon from here. I am sorry, Science World.

A cape made from golden silk orbweaver silk:

Further reading and listening:

Varmints! Podcast scorpions episode

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s almost Halloween! I’m on the third bag of gummi spiders, although they’ve changed the flavor from last year so I only eat the orange and yellow ones. The purple and green ones are in the bucket to give out to unsuspecting children.

Speaking of spiders…yes, I’m going there. I realize a lot of people are scared of spiders, but they’re beautiful, fascinating animals that are associated with Halloween. Don’t worry, I will try hard not to say anything that will set off anyone’s arachnophobia. Besides, there are some mysterious spiders out there that I think you’ll find really interesting.

First off, you don’t have to worry about gigantic spiders like in the movies. Spiders have an exoskeleton like other arthropods, and if a spider got too big, some researchers think its exoskeleton would weigh so much the spider wouldn’t be able to move. Not only that, spiders have a respiratory system that isn’t nearly as efficient as that of most vertebrates, so giant spiders couldn’t exist because they wouldn’t be able to get enough oxygen to function.

Specifically, some spiders have a tracheal system of breathing, like most insects and other arthropods also have. These are breathing tubes that allow air to pass through the exoskeleton and into the body, but it’s a passive process and spiders don’t actually breathe in and out. Other spiders have what are called book lungs. The book lung is made up of a stack of soft plates sort of like the pages of a book. Oxygen passes through the plates and is absorbed into the blood, which by the way is pale blue. This is also a passive process.

In other words, that picture that’s forever popping up on facebook of the enormous spider on the side of someone’s house, it’s photoshopped. In fact, pretty much any photo you see of a gigantic spider or insect or other arthropod is either photoshopped or made to look bigger by forced perspective. Also, spiders with wings are photoshopped, because no spider has ever had wings, even fossil spiders all the way back to the dawn of spider history, over 300 million years ago. So that’s one less thing to worry about.

Spiders live all over the world, everywhere except in the ocean and in Antarctica. The smallest spider known is .37 mm, so basically microscopic. It lives in Colombia and basically lives out its whole life not knowing most things about the world, like what whales are and how to operate a smart phone. On the other hand, the largest spider in the world is a tarantula called the goliath birdeater, and it probably also doesn’t know what whales are and how to use a smartphone. The goliath birdeater is the heaviest spider at a bit over 6 ounces, or 175 g, and has a legspan of 11inches, or 28 cm. Despite its name, it mostly eats insects but it will occasionally eat frogs, small rodents, small snakes, and worms. It lives in swampy areas in the rainforests of northeastern South America.

The spider with the biggest legspan—yes, I know, some of you are freaking out but I can’t do an episode about spiders and not talk about the biggest spiders. The spider with the biggest legspan is the giant huntsman, which lives around cave entrances in Laos, a country in southeast Asia. And it’s not much bigger than the goliath birdeater, with a legspan of one foot, or 30 cm.

All spiders produce silk but not all of them make webs. I won’t go into the process of how a spider generates silk, because it’s complicated and I just read about it and have already forgotten all the details, but spiders use silk to wrap up their eggs safely, line the walls of burrows to make a comfortable home, wrap up prey so it can’t escape, and of course make webs and get around without falling off tall things.

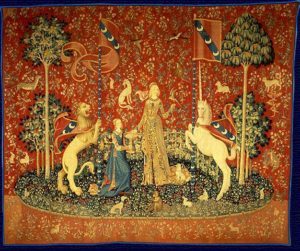

Most spider silk appears white, but the golden silk orb-weaver produces golden silk. The spider itself is gorgeous, with striped legs and a body that can be yellow, red, greenish, or brown, often with white spots and delicate patterns. It lives all over the world in warm climates, especially Australia. It builds webs that can be several feet across, or over a meter, and it occasionally catches and eats small birds as well as insects. One was even spotted eating a small snake that had been caught in its web. Its silk has occasionally been used to make cloth, but spider silk is difficult to collect in the quantities needed for textiles.

Most spiders eat insects, although one spider eats plants. Just one. It lives in Central America. Some baby spiders eat nectar until they get big enough to catch prey. Some spiders will scavenge on dead insects, some will eat fruit as well as insects, many eat pollen that gets caught on their webs, and some eat each other. Some spiders are adapted to swim in freshwater, and while they mostly eat aquatic insects, they will catch and eat small fish. Some spiders also catch and eat small birds and bats.

Basically, there are too many spiders to cover everything about them in one episode. Besides, what we all really want to know about are the mystery spiders. Because it’s almost Halloween!

Our first mystery spider is from Africa, specifically the jungles of central Africa. In 1938, an English couple, Reginald and Margurite Lloyd, were driving through the jungle when what looked like a monkey or cat stepped onto the dirt road. They stopped the car so it could cross the road, at which point they saw it was a spider. It looked like a tarantula but was huge, with a legspan of up to three feet, or almost a meter. Before Reginald Lloyd could grab his camera, the spider disappeared into the undergrowth.

Supposedly, the same giant spider was reported in the 1890s by a British missionary named Arthur John Simes. Some of his men got tangled in a huge web and a pair of spiders came out and attacked them. The larger of the spiders, presumably the female, was four feet across, or 1.2 meters. Simes was bitten but shot one of the spiders and was able to escape. He ultimately died of the bite.

This seems less than believable, to put it gently. The largest spider that catches prey with a web is our friend the golden silk orbweaver, but its legspan is only five inches across, or 12 cm. The biggest spiders in the world are tarantulas and other spiders that hunt actively, none of which build webs.

A more believable giant-spider mystery is called the up-island spider, which is supposed to be an extra-large variety of wolf spider from parts of Maine in the United States. Its legspan is supposed to be as much as 8 inches across, or 20 cm. Wolf spiders are common throughout the world, and while they look scary, they bite people very rarely and their venom is weak, no worse than a bee sting. The wolf spider with the biggest legspan is Hogna ingens, with a legspan less than 5 inches, or 12 cm. Hogna ingens lives on one island in the Maderia archipelago, and is a beautiful soft grey with white stripes on the legs. It’s critically endangered, but Bristol Zoo in England has a successful captive breeding program underway so it won’t go extinct. The species of wolf spider most commonly found in Maine is probably Tigrosa helluo, but it’s not very big, only a couple of inches across at most, or maybe five cm. It’s likely that the up-island spider is actually the Carolina wolf spider, which can have a legspan of four inches, or 10 cm, but I can tell you from personal experience that they look a whole lot bigger if you see one in your garage or basement when you flip on the light. The Carolina wolf spider does live in Maine, but it’s not very common in the area.

Zoologist Karl Shuker has a blog post from 2010, with some later updates, about spiders that are normal sized except for being blue, in species that aren’t normally blue. It’s an interesting post and I’ll link to it in the show notes if you want to read it and look at the pictures he posts. He discusses a number of blue spiders readers have reported to him, and while one seems to have been spraypainted blue, the rest appear naturally colored blue.

As it happens, there are lots of reports of blue spiders out there—and other blue invertebrates like woodlice. According Shuker’s post, some of these have been studied and found to be suffering from a virus called invertebrate iridovirus, or IIV. This infects invertebrates and sometimes is so highly concentrated in the animal’s tissues that it forms crystalline aggregations that emit blue iridescence and make the animal look blue. I should stress that you can’t catch IIV if you are a mammal, bird, reptile, fish, or anything else with a backbone, which I am assuming is most of my listeners.

The ancestors of spiders evolved around 380 million years ago, although those animals probably couldn’t generate silk. They did have eight legs, though. True spiders date to around 300 million years ago. Those spiders had silk spinnerets in the middle of the abdomen instead of at the end, and modern spiders appeared around 250 million years ago. We have fossil spiders and we also have spiders preserved in amber, the resin of certain trees that later fossilizes but remains at least partly transparent. We even have a spider web preserved in amber and dated to 110 million years ago, along with several insects that had been trapped in the web.

Spiders are closely related to whip scorpions, also called whip spiders because they look superficially similar to spiders in some ways except that they are HORRIFYING and I cannot look at pictures of them right now, I just can’t. While whip scorpions have eight legs, they only walk on six of them. The front pair are more like feelers and are elongated. Other whip scorpions have long, thin tails and are sometimes called vinegaroons, because if they’re disturbed they squirt a liquid that smells like vinegar. Some whip scorpions look a lot like scorpions. I don’t want to talk about scorpions. In fact, I’m just going to stop talking entirely, because while spiders don’t bother me, scorpions do and I cannot look at these pictures anymore, okay? If you want to learn about scorpions, Varmints! Podcast just released a scorpions episode. I’ll put a link in the show notes. Eventually I’ll manage to listen to it myself.

Happy Halloween?

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!