Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:25 — 14.2MB)

Thanks to Tobey and Janice this week for their suggestions of lesser-known sharks!

Further reading/watching:

CREATURE FEATURE: The Spinner Shark [this site has a great video of spinner sharks spinning up out of the water!]

Acanthorhachis, a new genus of shark from the Carboniferous (Westfalian) of Yorkshire, England

150 Year Old Fossil Mystery Solved [note: it is not actually solved]

The cartoon-eyed spurdog shark:

The spinner shark spinning out of the water:

The spinner shark not spinning (photo by Andy Murch):

A Listracanthus spine:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about three sharks you may have never heard of before! The first was suggested by my aunt Janice and the second by listener Tobey. The third is a mystery from the fossil record.

You may have heard about the findings of a study published in November of 2021, with headlines like “Venomous sharks invade the Thames!” My aunt Janice sent me a link to an article like this. Nobody is invading anything, though. The sharks belong where they are. It was their absence for decades that was a problem, and the study discovered that they’re back.

The Thames is a big river in southern England that empties into the North Sea near London. Because it flows through such a huge city, it’s pretty badly polluted despite attempts in the last few decades to clean it up. It was so polluted by the 1950s, in fact, that it was declared biologically dead. But after a lot of effort by conservationists, fish and other animals have moved back into the river and lots of birds now visit it too. It also doesn’t smell as bad as it used to. One of the fish now found again in the Thames is a small shark called the spurdog, or spiny dogfish.

The spurdog lives in many parts of the world, mostly in shallow water just off the coast, although it’s been found in deep water too. A big female can grow almost three feet long, or 85 cm, while males are smaller. It’s a bottom dweller that eats whatever animals it finds on the sea floor, including crabs, sea cucumbers, and shrimp, and it will also eat jellyfish, squid, and fish when it can catch them. It’s even been known to hunt in packs.

It’s gray-brown in color with little white spots, and it has large eyes that kind of look like the eyes of a cartoon shark. It also has a spine in front of each of its two dorsal fins, which can inject venom into potential predators. The venom isn’t deadly to humans but would definitely hurt, so please don’t try to pet a spurdog shark. If the shark feels threatened, it curls its body around into a sort of shark donut shape, which allows it to jab its spines into whatever is trying to grab it.

The spurdog used to be really common, and was an important food for many people. But so many of them were and are caught to be ground into fertilizer or used in pet food that they’re now considered vulnerable worldwide and critically endangered around Europe, where their numbers have dropped by 95% in the last few decades. It’s now a protected species in many areas.

The female spurdog retains her fertilized eggs in her body like a lot of sharks do. The eggs hatch inside her and the babies develop further before she gives birth to them and they swim off on their own. It takes up to two years before a pup is ready to be born, and females don’t reach maturity until they’re around 16 years old, so it’s going to take a long time for the species to bounce back from nearly being wiped out. Fortunately, the spurdog can live almost 70 years and possibly longer, if it’s not killed and ground up to fertilize someone’s lawn. The sharks like to give birth in shallow water around the mouths of rivers, where the water is well oxygenated and there’s lots of small food for their babies to eat, which is why they’ve moved back into the Thames.

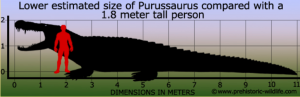

Next, Tobey suggested we talk about the spinner shark. It’s much bigger than the spurdog, sometimes growing as much as 10 feet long, or 3 meters. It lives in warm, shallow coastal water throughout much of the world. It has a pointy snout and is brown-gray with black tips on its tail and fins, and in fact it looks so much like the blacktip shark that it can be hard to tell the two species apart unless you get a really good look. It and the blacktip shark also share a unique feeding strategy that gives the spinner shark its name.

The shark eats a lot of fish, especially small fish that live in schools. When the spinner shark comes across a school of fish, it swims beneath it, then upward quickly through the school. As it swims it spins around and around like an American football, but unlike a football it bites and swallows fish as it goes. It can move so fast that it often shoots right out of the water, still spinning, up to 20 feet, or 6 meters, before falling back into the ocean. The blacktip shark sometimes does this too, but the spinner shark is an expert at this maneuver.

There’s a link in the show notes to a page where you can watch a video of spinner sharks spinning out of the water and flopping back down. It’s amazing and hilarious. Tobey mentioned that the spinner shark is an acrobatic shark, and it certainly is! It’s like a ballet dancer or figure skater, but with a lot more teeth. And fewer legs.

Because spinner sharks mainly eat fish, along with cephalopods, they almost never attack humans because they don’t consider humans to be food. Humans consider the spinner shark food, though, and they’re listed as vulnerable due to overhunting and habitat loss.

We’ll finish with a mystery shark. I’ve had Listracanthus on my ideas list for a couple of years, hoping that new information would come to light, but let’s go ahead and talk about it now. It’s too awesome to wait any longer.

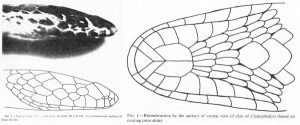

We know very little about Listracanthus even though it was around for at least 75 million years, since it’s an early shark or shark relative with a cartilaginous skeleton. Cartilage doesn’t fossilize very well compared to bone, so we don’t have much of an idea of what the shark looked like. What we do have are spines that grew all over the fish and that probably made it look like it was covered with bristles or even weird feathers. The spines are a type of denticle that could be up to 4 inches long, or 10 cm. They weren’t just spines, though. They were spines that had smaller spines growing from their sides, sort of like a feather has a main shaft with smaller shafts growing from the sides.

The spines are fairly common in the fossil record from parts of North America, dating from about 326 million years ago to about 251 million years ago. Listracanthus was closely related to another spiny shark-like fish, Acanthorhachis, whose spines have been found in parts of Europe and who lived around 310 million years ago, but whose spines are less than 3 inches long at most, or 7 cm.

Some researchers think the spines were only present on parts of the shark, maybe just the head or down the back, but others think the sharks were covered with the spines. Many times, lots and lots of the spines are found together and probably belong to a single individual whose body didn’t fossilize, only its spines. Some researchers even think that the flattened denticles from a shark or shark relation called Petrodus, which is found in the same areas at the same times as Listracanthus, might actually be Listracanthus belly denticles.

The spines probably pointed backwards toward the tail, which would reduce drag as the fish swam, and they might have been for display or for protection from predators, or of course both. The main parts of the spine were also hollow and there’s evidence there were capillaries inside, so they might have had a chemosensory or electrosensory function too.

Modern sharks have denticles that make their skin rough, sort of like sandpaper. One modern shark, the sandy dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula, which is common in shallow water off the coasts of western Europe and northern Africa, and in the Mediterranean, has especially rough denticles on its tail. They aren’t precisely spines, but they’re more than just little rough patches. The sandy dogfish is a small, slender shark that barely grows more than about three feet long, or about a meter, and it eats anything it can catch. Young dogfish especially like small crustaceans, and sometimes they catch an animal that’s too big to swallow whole. In that case, the shark sticks the animal on the denticles near its tail, which anchors it in place so it can tear bite-sized pieces off. Some other sharks do this too, so it’s possible that Listracanthus and its relations may have used its spines for similar behavior.

We don’t know much about these sharks because all we have are their spines. Only one probable specimen has been found, by a paleontologist named Rainer Zangerl. Dr. Zangerl found the remains of an eel-like shark in Indiana that was covered in spines, but unfortunately as the rock dried out after being uncovered, the fossil literally disintegrated into dust.

In August of 2019, a fossil hunter posted on an online forum for fossil enthusiasts to say he’d found a Listracanthus specimen. He posted pictures, although since the fossil hasn’t been prepared it isn’t much to look at. It’s just an undulating bump down a piece of shale that kind of looks like a dead snake. Fortunately, the man in question, who goes by RCFossils, knew instantly what he’d found. He also knew better than to try to clean it up himself. Instead, he’s been working on trying to find a professional interested in taking the project on. In May of 2022 he posted again to say he’d managed to get an X-ray of the fossil, which shows a backbone but no sign of a skull. He’s having trouble finding anyone who has the time and interest in studying the fossil, but hopefully he’ll find someone soon and we’ll all learn more about this mysterious pointy shark.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!