Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:17 — 13.4MB)

This week’s episode is about some interesting eels, including the Brantevik eel.

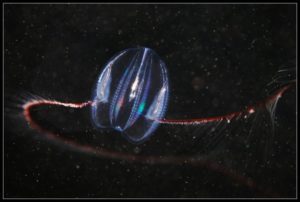

A European eel:

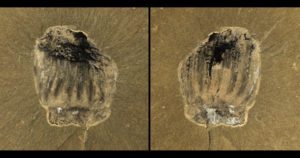

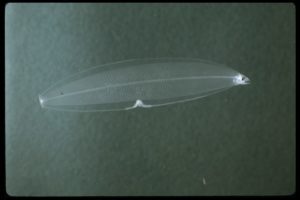

A leptocephalus, aka an eel larva:

A moray eel. It has those jaws you can see and another set of jaws in its throat:

Episode transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week, we’re going to learn about the Brantevik eel and some other eels, including an eel mystery.

The Brantevik eel is an individual European eel, not a separate species. Its friends knew it as Åle, which I’ve probably misprounounced, so I’m nicknaming it Ollie. So what’s so interesting about Ollie the eel?

First, let’s learn a little bit about the European eel in general to give some background. It’s endangered these days due to overfishing, pollution, and other factors, but it used to be incredibly common. It lives throughout Europe, from the Mediterranean to Iceland, and has been a popular food for centuries.

The European eel hatches in the ocean into a larval stage that looks sort of like a transparent flat tadpole, shaped roughly like a leaf. Over the next six months to three years, the larvae swim through the ocean currents, closer and closer to Europe, feeding on microscopic jellyfish and plankton. Toward the end of this journey, they grow into their next phase, where they resemble eels instead of tadpoles, but are mostly transparent. They’re called glass eels at this point. The glass eels make their way into rivers and other estuaries and slowly migrate upstream. Once a glass eel is in a good environment it metamorphoses again into an elver, which is basically a small eel. As it grows it gains more pigment until it’s called a yellow eel. Over the next decade or two it grows and matures, until it reaches its adult length—anywhere from two to five feet, or 60 cm to 1.5 meters. When it’s fully mature, its belly turns white and its sides silver, which is why it’s called a silver eel at this stage. Silver eels migrate more than 4,000 miles, or 6500 km, back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn, lay eggs, and die.

One interesting thing about the European eel is that during a lot of its life, it has no gender. Its gender is determined only when it grows into a yellow eel, and then it’s mostly determined by environmental factors, not genetics.

Until the late 19th century, everyone thought these different stages—larva, glass eel, elver, yellow eel, and silver eel—were all separate animals. No one knew how or even if eels reproduced. The ancient Greeks thought eels were a type of worm that appeared spontaneously from rotting vegetation. Some people thought eels mated with snakes or some types of fish. By the 1950s the eel’s life cycle was more or less understood, but many researchers thought the European eels never made it to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. It was just too far, so they thought the eels that arrived in Europe were all larvae of the American eel, which is almost identical in appearance to the European eel. The Sargasso Sea is off the coast of the Bahamas, so the American eel doesn’t have nearly as far to travel. These days we know from DNA studies that the American and European eels are different species. The European eel is just a world-class swimmer.

European eels are nocturnal and may live in fresh water, brackish water, or sometimes they remain in the ocean and live in salt water, generally in harbors and shallows. They eat anything they can catch, from fish to crustaceans, from insect larvae to dead things, and on wet nights they’ll sometimes emerge from the water and slide around on land eating worms and slugs. Many populations don’t eat at all during the winter.

Now, back to the Brantevik eel. Brantevik is a tiny fishing village in Sweden. In 1859, an eight-year-old boy named Samuel Nilsson caught an eel and released it into his family’s well to eat insect larvae and other pests. This was a common practice at the time when water wasn’t treated, so the fewer creepy-crawlies in the water, the better.

And there the eel stayed. Ollie got famous over the years, at least in Sweden. Its 100th well anniversary was celebrated in 1959, and children’s books and even movies featured it. But in summer of 2014, Ollie died. Its well is now on the property of Tomas Kjellman, whose family bought the cottage and its well in 1962. Everyone knew about the resident eel, which the family treated as something of a pet. In fact, they discovered it was dead when they opened the well’s cover to show the eel to some visiting friends.

Ollie’s remains were removed from the well and shoved in the family’s freezer, and later sent to be analyzed at the Swedish University of Agricultural Science’s Institute of Freshwater Research. That analysis confirmed that Ollie was over 150 years old.

In the wild, European eels don’t usually live longer than twenty years, and ten years is more likely. But in captivity, where eels don’t spawn, they can live a long time. A female European eel named Putte lived over 85 years in an aquarium at Halsinborgs Museum in Sweden.

What most people don’t know is that Ollie wasn’t alone. Another eel still lives in the well and is doing just fine, but it’s younger, only about 110 years old.

The larvae of European eels are small, only about three inches at the most, or 7.5 cm. Even conger eel larvae are small, only 4 inches long, or 10 cm, and conger eels can grow 10 feet long, or 3 meters. But on January 31, 1930, a Danish research ship caught an eel larva 900 feet deep off the coast of South Africa—and that larva was six feet 1.5 inches long, or 1.85 meters.

Scientists boggled at the thought that this six-foot eel larva might grow into an eel more than 50 feet long, or 15 meters, raising the very real possibility that this unknown eel might be the basis of many sea serpent sightings.

The larva was preserved and has been studied extensively. In 1958, a similar eel larva was caught off New Zealand. It and the 1930 specimen were determined to belong to the same species, which was named Leptocephalus giganteus. Leptocephalus, incidentally, is a catchall genus for all eel larvae, which can be extremely hard to tell apart.

In 1966 two more of the larvae were discovered in the stomach of a western Atlantic lancet fish. They were much smaller than the others, though—only four inches and eleven inches long, or 10 cm and 28 cm. Dr. David G. Smith, an ichthyologist at Miami University, determined that the eel larvae were actually not true eels at all, but larvae of a spiny eel. Deep-sea spiny eels are fish that look like eels but they’re not closely related. And while spiny eels do have a larval form that resembles that of a true eel, they’re much different in one important way. Spiny eel larvae grow larger than the adults, then shrink when they develop into their mature form.

So the six-foot eel larvae, if it had lived, would have eventually developed into a spiny eel no more than six feet long itself at the most, and probably shorter.

More recent research has called Dr. Smith’s findings into question, and many scientists today consider L. giganteus to be the larvae of a short-tailed eel, which is a true eel—but not a type that grows much larger than its larvae. So either way, the adult form would probably not be much longer than a conger eel.

But…we still don’t have an adult. So there’s still a possibility that a very big deep-living marine eel is swimming around in the world’s oceans right now.

The longest known eel is the slender giant moray, which can reach 13 feet in length, or 4 meters. Morays are interesting eels for sure. They live in the ocean, especially around coral reefs, and have two sets of jaws, their regular jaws with lots of hooked teeth, and a second set in the throat that are called pharyngeal jaws, which also have teeth. The moray uses the second set of jaws to help grab and swallow prey that might otherwise wriggle out of its mouth. The moray has a strong bite and doesn’t see very well, although its sense of smell is excellent. This occasionally causes problems for divers who think it would be fun to feed an eel and end up with a finger bitten off. Don’t feed the eels, okay? Not only that, but a moray can’t release its bite even if it’s dead, so if one bites a diver, someone has to pry the eel’s jaws open before the bite can be treated. And as if all that wasn’t warning enough to not feed wild animals, and frankly just stay out of the water entirely, research suggests that some morays are venomous. Oh, and the giant moray sometimes hunts with a fish called the roving coralgrouper, which grows to some four feet long, or 120 cm, which is a rare example of interspecies cooperative hunting.

Some people believe that at least some sightings of the Loch Ness monster can be attributed to eels—European eels, in this case. An eel can’t stick its head out of the water like Nessie is supposed to do, but it does sometimes swim on its side close to the water’s surface, which could result in sightings of a string of many humps undulating through the water. But while eels do live in and around Loch Ness, it’s unlikely that any European eel would grow much larger than around five feet, or 1.5 meters. Still, you never know. Loch Ness is the right habitat for an eel to grow to its maximum size, and while we have learned a lot about eels in general, and the European eel in particular, since Ollie was released into a well in Brantevik, we certainly don’t know everything about them.

One last note about eel larvae. Occasionally on facebook and other social media, well-meaning people will share warnings about a nearly invisible wormlike parasite that can be found in drinking water, with pictures of, you guessed it, eel larvae. Eel larvae are not parasites, are not found in fresh water at all, and even if you did accidentally swallow one, you’d just digest it and get a little protein out of the bargain. So you don’t need to worry about those clickbait warnings, the eels do.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!