Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:56 — 13.2MB)

Thanks to Zachary and Oran for this week’s topic, some little animals that bounce around like tiny kangaroos!

Further reading:

Evolution of Kangaroo-Like Jerboas Sheds Light on Limb Development

Supposedly extinct kangaroo rat resurfaces after 30 years

High-Speed Videos Show Kangaroo Rats Using Ninja-Style Kicks to Escape Snakes

Williams’s jerboa [picture by Mohammad Amin Ghaffari – https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/177950563, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115769436]:

A drawing of a jerboa skeleton. LEGS FOR DAYS:

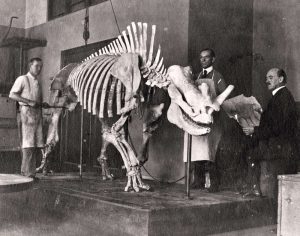

The San Quintin kangaroo rat lives! [photo from article linked above]

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about two cute little animals suggested by Zachary and Oran! Both of these animals are rodents but although they look remarkably alike in some unusual ways, they’re not actually all that closely related.

First, Zachary suggested the jerboa. We talked about the pygmy jerboa in episode 136, but we haven’t talked about jerboas in general. It’s a small rodent that’s native to the deserts of Asia, north Africa, and the Middle East. It’s usually brown or tan with some darker shading on the back and tail. It looks sort of like a gerbil with long ears, long hind legs, and a tuft at the end of the tail. Its front legs are short and it has an adorable whiskery nose.

The reason the jerboa’s hind legs are so long while its front legs are really short is that it jumps around on its hind legs like a kangaroo. Not only can it jump really fast, up to 15 mph, or 24 km/h, it can change directions incredibly fast too. This helps it evade predators, because most animals are fastest when running in a straight line. The jerboa bounces in all sorts of directions, hopping or just running on its long hind legs, with its long tail held out for balance. It can also run on all fours with its short front legs helping it maneuver, but for the most part it’s a bipedal animal. It has tufts of stiff hairs under its toes that help it run through loose sand.

The jerboa eats plants, although sometimes if it finds a nice juicy insect it will eat it too. Mostly it just eats leaves, bulbs, roots, and some seeds. It gets all of the moisture it needs from its diet, which is good because it lives in the desert where there’s not much water available.

Some species of jerboa mainly eat insects and spiders, and some have short ears instead of long ears. This is the case for the thick-tailed pygmy jerboa that lives in parts of China, Mongolia, and Russia. Its head and body only measures about two inches long, or almost 5 cm, but its tail is twice that length. The reason it’s called a thick-tailed jerboa is because it stores fat at the base of its tail, which makes the tail look thick compared to many rodent tails.

The jerboa is mostly active at dawn and dusk, although some species are fully nocturnal. It spends the day in a burrow it digs in sand or dirt. A jerboa will usually have more than one burrow in its territory, with the entrances usually hidden under a bush or some other plant. Different burrows have different purposes. Some have numerous entrances and lots of side tunnels but are relatively shallow, which is useful if the jerboa lives in an area with a rainy season. A shallow burrow won’t flood if it rains a lot. Some burrows are temporary, which the jerboa may dig if it’s out and about during the day looking for food. A mother jerboa will dig a burrow with a roomy nesting chamber to raise her babies, and a jerboa’s winter burrow has a nesting chamber that’s deep underground to help it stay warm. Some species of jerboa construct unusual burrows, like the lesser Egyptian jerboa that has spiral-shaped burrows with storage chambers. Most jerboas are solitary animals, although sometimes a group will hibernate together in winter to help everyone stay warmer.

Scientists have been studying the jerboa to learn how different animals have evolved radically different leg lengths. The jerboa’s incredibly long hind legs are very different from its very short front legs, but it evolved from animals that had four short legs. But jerboas are born with four short legs, and as the babies grow up their hind legs grow longer and longer.

The jerboa is an incredibly efficient runner. Some species can jump as far as six feet in a single bound, or 1.8 meters, and up to three feet, or 90 cm, straight up.

The jerboa isn’t the only rodent that hops on its hind legs like a kangaroo. The kangaroo rat does too, and it’s Oran’s suggestion. Oran pointed out that a long time ago, I think in the humans episode, I said that humans are the only fully bipedal mammal, meaning we only ever walk on our hind legs. (Crawling when you’re a baby or trying to find something under the couch don’t count.) I was wrong about that for sure, because the kangaroo rat, the jerboa, and a few other mammals are also bipedal.

The kangaroo rat is native to parts of western North America. It looks a lot like a jerboa, with long hind legs and a long tail, although its ears are smaller. But the kangaroo rat and the jerboa aren’t closely related, although both are rodents. Their similarities are due to convergent evolution, since both animals live in very similar environments with the same selective pressures.

The largest species of kangaroo rat, the giant kangaroo rat, grows around 6 inches long, or 15 cm, with a tail about 8 inches long, or 20 cm. It can jump even longer than the jerboa although it doesn’t move as fast on average.

Like the jerboa, the kangaroo rat can change directions quickly, and it’s also mostly nocturnal and spends the day in a burrow. Some species spend almost all the time in burrows, only emerging for about an hour a night to gather seeds. Since owls like to eat kangaroo rats, you can’t blame them for wanting to stay underground as much as possible.

Snakes also like to eat kangaroo rats, especially the sidewinder rattlesnake. It’s a fast predator with venom that can easily kill a little kangaroo rat, but the kangaroo rat isn’t helpless. A study published in 2019 filmed interactions in the wild between the desert kangaroo rat and the sidewinder, using high-speed cameras. They had to use high-speed cameras because the snakes can go from completely unmoving to a strike in under 100 milliseconds. That’s less time than it takes you to blink. But the kangaroo rat can react in even less time, as little as 38 milliseconds after the snake starts to move. A lot of time the kangaroo rat will completely leap out of range of the snake, but if it can’t manage that, it will kick the snake with its long hind legs, which are strong enough to knock the snake away. Little fuzzy ninjas.

Unlike the jerboa, the kangaroo rat mostly eats seeds. The jerboa’s teeth aren’t very strong so it can’t bite through hard seeds, but the kangaroo rat’s teeth are just fine with seeds. The kangaroo rat also has cheek pouches, and it will carry lots of seeds home to its burrow. It keeps extra seeds in special burrow chambers called larders.

The kangaroo rat sometimes lives in colonies that can number in the hundreds, but it’s still a mostly solitary animal. It has its own burrow that’s separate from the burrows of other members of its colony, and it doesn’t share food or interact very much with its neighbors. It will communicate with other kangaroo rats by drumming its hind feet on the ground, including warning its neighbors to stay away and alerting them to predators in the area.

The kangaroo rat is vulnerable to habitat loss, since it mostly lives in desert grassland and humans tend to view that kind of land as useless and in need of development. An example of this is the San Quintin kangaroo rat, which is only found in western Baja California in Mexico. Only two large colonies were known when it was discovered by science in 1925, although it used to be much more widespread. But in the decades since 1925, the land was developed for agriculture until by 1986 the two colonies were completely wiped out. Scientists worried the species had gone extinct. Then, in 2017, a colony was discovered in a nature preserve and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Other colonies have been discovered on farmland that has been abandoned due to drought. Still, the San Quintin kangaroo rat is critically endangered.

The kangaroo rat is actually helpful for the environment. Because it stores seeds underground, and sometimes forgets where it put them, it helps native plants spread. Its burrows help increase soil fertility and the spread of water through the soil. This is similar to the jerboa, which also eats enough insects to help reduce the number of agricultural pests in some areas.

There are also two species of kangaroo mouse, which are closely related to kangaroo rats. They mostly live in the state of Nevada in North America. There are also jumping mice that look like ordinary mice but with long hind legs. It also has cheek pouches. While some jumping mice live in western North America, some live in northeastern North America and Canada and are adapted to cold weather and long winters. One species of jumping mouse lives in the mountains in parts of China. There’s also a larger jumping rodent called the springhare that lives in parts of Africa, and which is about the size of a squirrel or a small rabbit. Like all these other rodents, it’s bipedal and hops on its hind legs like a little kangaroo, using its long tail for balance and to prop itself up when it’s standing. It mostly eats plants but will sometimes eat insects, and it spends most of the day in burrows. There’s also a hopping mouse native to Australia, which is a rodent with long hind legs and a long tail and long ears. It’s not closely related to the jerboa or the kangaroo rat, but it looks a lot like both because of convergent evolution. It mostly eats seeds.

All these animals are rodents, but Australia also has another animal called the kultarr that looks a lot like the kangaroo rat and the jerboa. It’s not a rodent, though. It’s actually a marsupial that’s completely unrelated to rodents although it looks like a rodent. That’s definitely what you call convergent evolution.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!