Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:52 — 16.3MB)

This week’s episode is about the Carolina parakeet, a cheerful, pretty bird that was once common in the central and eastern United States but which has been extinct for a century. Thanks to Maureen for the suggestion! I’ve paired it with the elephant bird, a gigantic extinct bird that we don’t know much about except for its enormous eggs.

The Carolina parakeet, deceased:

An ex-parrot next to an ex-passenger pigeon:

A still from the 1937? Nelson video:

The 2014 mystery parakeet photo:

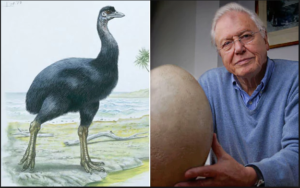

An elephant bird, an elephant bird egg, and Sir David Attenborough (right):

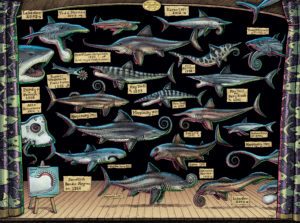

Further Reading/Watching:

Here’s a close evaluation of the Nelson video taken in the late 1930s, supposedly in the Okefenokee Swamp.

I can’t get the Nelson video to embed properly, so here’s a link to it. You’ll need to scroll down to the bottom of the page for a decent-sized version that will play.

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode is about two birds, one small and one really big, and both extinct. Probably.

First, let’s learn about the Carolina parakeet, a suggestion by listener Maureen. It was a type of small parrot that was common throughout a big part of the United States, as far west as Nebraska and parts of Colorado and as far north as New York, and as far south as Florida and around the Gulf of Mexico. It had a yellow and orange head and a green body with some yellow markings, and was about the size of a mourning dove or a passenger pigeon.

This story of extinction mirrors that of the passenger pigeon in many ways. The Carolina parakeet lived in forests and swamps in big, noisy flocks and ate fruit and seeds. But when European settlers moved in, turning forests into farmland and shooting birds that were considered pests, its numbers started to decline. In addition, the bird was frequently captured for sale in the pet trade and hunted for its feathers, which were used to decorate hats. Part of the reason it was so easy to kill was that if a wounded bird’s cries were heard by other Carolina parakeets—and they probably would hear it, since these birds were loud, with calls carrying up to two miles—the whole flock would come flying out to help the wounded bird.

By 1860 the Carolina parakeet was rare anywhere except the swamps of central Florida, and by 1904 it was extinct in the wild. The last captive bird died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, which was not only the same zoo where the last passenger pigeon died in 1914, it was the same cage. It was declared extinct in 1939.

We don’t know a lot about the Carolina parakeet even though it survived into the 20th century because no one made any particular study of the bird. John Audubon painted it and made some notes, and we have a lot of skins, skeletons, and some stuffed specimens, but that’s about it. There were two subspecies, one that lived to the east of the Appalachian mountain range, and one that lived to the west, that went extinct sooner than the eastern subspecies and was more bluish-green than green.

One interesting thing that Audubon noted is that cats that killed and ate Carolina parakeets died. The bird ate a lot of cockleburs, and the cocklebur’s seed is poisonous—so much so that livestock die from eating them. If you listened to episode 31, venomous animals, you may remember the Africa spur-winged goose that eats toxic blister beetles, collects the toxin in its tissues, and is therefore poisonous to eat. It’s probable that the Carolina parakeet did the same with cocklebur toxins.

Sightings of the bird in the wild occurred through the 1920s and 30s. A whole flock of some 30 birds was spotted in Florida in 1920, and in 1926 three nesting pairs were seen in Okeechobee County, Florida by the Curator of Birds at Florida University, Charles Doe. Doe was so excited to find these supposedly extinct birds that he ROBBED ALL THREE PAIRS OF THEIR EGGS. Because that man was an idiot and he will go down in history as an idiot. Charles E. Doe, Idiot, it probably says on his tombstone. His egg-shaped tombstone, probably.

In the mid-1930s ornithologist Alexander Sprunt Jr collected a number of sightings of Carolina parakeets in the Santee Swamp in South Carolina. Numerous trained bird wardens and ornithologists saw the birds, but it didn’t matter. In 1938 the Santee River was dammed and a power plant built, which radically changed the area ecosystem, and much of the surrounding forest was cut down and the swampland drained during the construction process. No one has reported any parakeet sightings since then.

Of course, the southeast still has lots of swampland, some of it all but impenetrable. The Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia and Florida is close to half a million acres, or more than 1700 square kilometers, and most of that area has been a national wildlife refuge since 1974. In 1937 or a little after, someone shot about 50 seconds of color film footage of three green birds in the Okefenokee. The footage is usually attributed to a man named Oren, or Orsen, Stemville.

In the early 1950s an Audubon lecturer named Dee Jay Nelson bought an old film camera from a boat operator in the Okefenokee Swamp. The box it came in contained eight rolls of processed 16mm film, but Nelson didn’t actually view those rolls for about 15 years. One roll contained footage of alligators and toads native to the Okefenokee, and in between those was some strange footage of three green birds.

Roger Tory Peterson, a member of the American Ornithologists’ Union, got a copy of the film and presented it to the society for analysis in 1969. There was no consensus as to whether the birds were feral pet parakeets of some kind or Carolina parakeets. Peterson misplaced his copy of the film and when Nelson was contacted by the society in 1979, he said he had lost the original. But in 2005 the copy turned up in Peterson’s effects after he died. At that point the Ornithologists’ Union analyzed the film again and concluded that not only are the birds not Carolina parakeets, they appear to have been artificially colored to look like Carolina parakeets. In other words, it was a hoax—and not even a very good one. It’s possible that only one of the birds was even real; the others were probably taxidermied birds or models. Nelson’s story about how he found the footage is fishy anyway. In the 1960s Nelson was a screen-tour lecturer from Montana, so he may have shot the footage himself to illustrate some project that never got off the ground.

The 2005 analysis of the footage was thorough. The society even brought in botanists to find out what kind of tree is shown in the film, but they were unable to identify it and said that the Spanish moss draped on the branches appears to have been placed there instead of growing there naturally. I’ll put a link in the show notes to the society’s close notation of the footage, practically frame by frame. The film is archived with the Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology, and I’ll include a link to the video too.

The problem with sightings is that the green parakeet, a species native to Central America as far north as the southern tip of Texas, and the red-masked parakeet from Ecuador and Peru, look similar to the Carolina parakeet and have been pets in the United States for a long time, as have many other parrot species. In Florida in particular, escaped parrots sometimes survive and band together in breeding colonies, and by the 1920s had already begun to do so. So if the Nelson footage isn’t a hoax, it might be mistaken identity.

While I’m pretty nearly certain that the Carolina parakeet really is extinct, if it still manages to hang on in the depths of the Okefenokee swamp or elsewhere, anyone who’s observed it might assume they’ve only seen a red-masked parakeet or something.

On April 1, 2009 someone posted an article that looked like a press release from Cornell University about the discovery of a population of Carolina Parakeet in northern Honduras. It was an April fool’s joke, but it was so convincing that people still claim it’s real. I really hate April fool’s, by the way.

In January 2014, someone posted an interesting picture to a bird forum, saying her son took the picture at their home in southern Georgia in 2010 and asking what kind of parrot it was. The bird’s a dead ringer for a Carolina parakeet sitting in an apple tree. The poster deleted the thread later, upset at being accused of posting a hoaxed picture. This being the internet, no one can agree on whether the picture is real or shopped. It looks real to me, but while it might be a young yellow-headed Amazon parrot, the red cheeks aren’t a yellow-headed trait. So it’s a mystery.

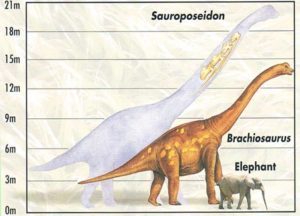

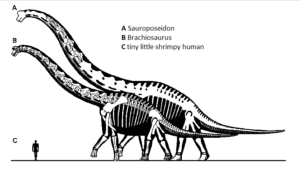

From this small, brightly colored bird we go to a gigantic one. The elephant bird stood about ten feet tall head to toe, or 3 m, and while it looks superficially like an ostrich, it was more closely related to the tiny kiwi of New Zealand. But the elephant bird only lived in Madagascar.

It’s possible that stories about the roc, an eagle so big it could pick up elephants, were actually garbled stories about the elephant bird. That’s where the name elephant bird comes from, incidentally. The real life elephant bird probably became the fabled roc not from sightings of the bird but from its eggs. The eggs were enormous, the largest bird egg known and possibly the largest egg ever known, some over a foot long or about 34 cm, and big enough to hold over two gallons of liquid, or seven and a half liters. We’re getting close to watermelon sized here.

In 1930, in the southernmost point of Western Australia, two boys were playing along the beach and discovered a gigantic egg buried in a sand dune. They took it home, where no one had any idea what bird might have laid it. It was twice the size of an ostrich egg. Eventually it was given to the Western Australia Museum, and in 1962 a naturalist examined it and identified it as the egg of an elephant bird. Another elephant bird egg was found in western Australia by three children in 1992. But what were they doing in Australia? Elephant birds can’t fly, were never native to Australia or anywhere else except Madagascar, and anyway by 1930 they were certainly extinct.

Well, eggs can float, especially in saltwater and especially if the embryo inside has died, as would happen if the egg was washed out of its nest and into cold water. The elephant bird liked to lay its eggs in sand along the beach or rivers. Sometimes they would be washed out to sea. People who found elephant bird eggs without knowing what kind of enormous bird they would hatch into would naturally tell stories about them, like the roc. And even now, when there are no elephant birds around to lay new eggs, intact eggs are still occasionally found. The shells of elephant bird eggs were as much as 4 mm thick, which doesn’t sound like much but is way thicker than any other egg shell. That’s over an eighth of an inch thick.

So these were big, tough eggs that weren’t easily destroyed. Moreover, the egg found in Australia in 1992 was dated to 2,000 years old and was found in deposits of sand that had been laid down a few thousand years ago too. Both eggs had been in place for millennia until those meddling kids dug them up.

In 1974 a King Penguin egg was found floating near the beach very near where the 1930 elephant bird egg was found, having drifted some 1200 miles, or 2,000 km, in only a matter of weeks. In 1991 another King Penguin egg was found in the same region. This one was covered in barnacles and algae, but both were easily removed without damaging the egg. And in the early 1990s, a man working on a dredge in the Timor Sea, which is part of the Indian Ocean, spotted an ostrich egg in the water and retrieved it. It was so heavily weighted down with algae that it wasn’t bobbing along at the surface, but it was still floating under the surface and was intact. Any barnacles that had grown on the elephant bird eggs would have been sandblasted off by wind once the eggs were beached. The 1930 egg had one surface polished smooth from exposure to wind.

The elephant bird ate plants, probably nuts and fruit. Some researchers think the fruit of some rare species of palm trees on Madagascar were eaten and dispersed by the elephant bird. It had muscular legs like an ostrich but was so heavy, it probably couldn’t run very fast.

We’re not sure when the elephant bird went extinct. Some egg shells have been dated to about 1,000 years ago and that seems to be the latest signs of elephant birds. But as late as the 17th century native people from Madagascar were adamant that it still lived in hard-to-travel swamps.

We do have a pretty good idea of why the elephant bird went extinct, though. The eggshells were used as buckets and bowls, and archaeological studies have found plenty of charred shells in cooking fires. One elephant bird egg could feed an entire family. The adult birds were also hunted and eaten. Not only that, when European settlers decided they’d like to live in Madagascar now, thanks very much, you native people can just shift over and give us all the good land, deforestation and overhunting combined to finish off the elephant bird forever.

Like other recently extinct animals, the elephant bird is a good candidate for de-extinction once cloning technology is perfected. But if we do get the elephant bird back, we have to promise not to eat all its eggs.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!